5 Movies From The '80s That Perfectly Capture The Meaning Of Life

The best films are the ones that give you ideas. While most scripted dramas come packaged with easy morals, not all of them are profound. You may walk away from, say, "Ghostbusters" with a smile on your face and a dazzle in your eyes (it is, after all, quite funny and visually impressive), but one won't necessarily take inspiration from it. Indeed, there's a notable scene in "Ghostbusters" wherein Winston (Ernie Hudson) asks Ray (Dan Aykroyd) if their ghostbusting might have serious theological implications about the nature of the universe. Ray avoids the question and turns on the radio. The theme of "Ghostbusters" is the power of blue-collar work, and the deliberate ignoring of the profound.

Some films, however, impart to you — sometimes without you ever noticing — a reflection on life that may alter your thinking or behavior. Some of them may match your extant worldview. Others may introduce you to a new way of thinking. And you can never be sure what these movies are while you're watching them. It wouldn't be until years later, when you find yourself still thinking about a movie, that you realize how much it introduced you to, how much it codified your worldview.

The following films all have vastly different philosophies. Some are peaceful and kind. Some are bleak and nihilistic. Some represent the varied commercial-heavy philosophies of the 1980s. The '80s were a time of commercial ascendance and increased rebellion against a frustratingly conservative America. Movies tended to reflect either the fun or the horrors of that time. All of these films, however, capture an important facet of the human condition

Fitzcarraldo (1982) is about futility

Werner Herzog's 1982 epic "Fitzcarraldo" is as close as one might come to seeing the myth of Sisyphus on film. Sisyphus was sentenced in the afterlife to eternally roll a boulder up a hill, toiling and sweating in perpetuity. When the boulder reached the top, it merely rolled back down again, and Sisyphus had to start over. It is the ultimate symbol of futility. Of course, in the 1940s, Albert Camus came along and wrote an essay called "The Myth of Sisyphus" that reframed the dead man's toil as something positive. If there is no meaning to life, Camus argued, then the toil becomes the thing that defines us. We can take pride, and even pleasure, in our immediate tasks. Sisyphus made his rock "his thing."

Herzog seems to have a bleak worldview. He often makes dramas and documentaries about how human endeavors are futile, and how the natural world awaits, indifferently, to re-consume us. All human efforts are foolish. And yet, we are mad for our efforts. They consume us. They give us meaning, even as they crumble in front of us. "Fitzcarraldo" is about an ambitious Irishman named Brian Fitzgerald (Klaus Kinski) who aims to build an opera house deep in the jungles of Peru. The area is booming because of the rubber tree trade, and Fitzgerald thinks he can bring culture to the area. He just needs to float a boat full of materials down a river and haul it over a small land bridge.

The "haul" is the bulk of the movie, and Herzog decided to actually haul a real ship over a real land bridge. It's as soul-crushingly difficult as it sounds. It's ambitious, horrifying, and destructive. Our dreams power us, but are also the ultimate burden.

Born in Flames (1983) is about revolution

Lizzie Borden's "Born in Flames" is a hand grenade of a movie. It's a sci-fi fantasy, set in the near future, about a decade after an ultra-Left Wing revolution has taken place. Although this is a dream future for liberals, there are still insidious, and sexist, forces at work. "Born in Flames" points out that we have it backwards when it comes to the way politics and culture interact. We may think that politics informs and shapes culture, but it's really quite the opposite. The main story follows two women who each run a Leftist radio station that carries revolutionary rhetoric to the masses. There is Honey (Honey), the gentler of the pair, and there is Isabel (Adele Bertei) a militant lesbian armed with more fiery rhetoric.

While these two radio stations are rivals, and the world lives under a presumably utopian socialist-democratic utopia, there is still a large, noisy contingent of jerk in the world who want to harm women and regularly attack women on the street. The president has called for women to return to the kitchen where they would, he says, be paid for doing housework. Conservatism will never let up. The world's women have united, however, calling out attackers and rushing to help all of womenkind. The queer women of the world, especially queer women of color, are our punk rock saviors. There is no more aggressive rebuke of Reagan's America than "Born in Flames." It may be one of the most important movies of its decade.

And it's exciting to watch. Although a lot of screen time is devoted to Honey or Isabel ranting about their political viewpoints, the rhetoric is riveting. It divides up the fine details of Black feminism vs. white feminism, all arguments against it wither.

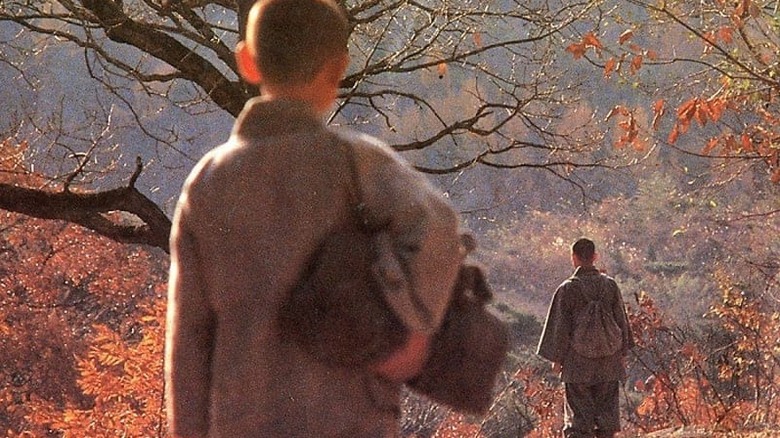

Why Has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East? (1989) is about peace

One of the calmest movies ever made, Bae Yong-kyun's "Why Has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East?" is about three monks on their various journeys through Zen Buddhism. The film was made with a single camera, used a lot of prologned takes, and edited by hand by the director and the director alone. The making of the film is about the Zen of construction, the slow repetitive actions that clear our minds and move us toward Enlightenment.

The film is constructed around Zen koans (that is: questioning aphorisms meant to clear the mind of conscious thought), notably "What did my face look like before I was born?" and the more abstract "When the moon takes my heart (that is: when I reach Enlightenment), where does the Master of my being go?" It's about the destruction of the ego, the ridding of all heavy thoughts. The main character, Ki-bong (Sin Won-sop) enters a monastary looking for meaning. An orphan boy Hae-jin (Hee-jin Hwang) is being cared for at the monastery. And an elderly monk, Hye-gok (Yi Pan-yong) has become a recluse, avoiding the ego that might come from wisdom.

The film is contemplative and melancholy. There is a lot of suffering and death in the world, but a lot of transmigration, re-birth, and spiritual freedom. Watching "Why Has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East?" is like meditating. The long, lingering shots let us see the beauty of the natural world, the artificiality of the modern world, and the slow, luminous growth of the soul. It's one of the most religious films ever, but one needn't be a practicing Buddhist to derived wisdom from it.

How to Get Ahead in Advertising (1989) is about commercialism

Thanks to the laissez-faire capitalism of Ronald Reagan, commercialism spiked in the 1980s. Commercials were everywhere, everywhere, everywhere. Entertainment for kids was heavily deregulated in the decade, and a generation of kids was raised on essentially toy commercials masquerading as dramas. Gen-X saw advertising as the single most soulless occupation one could apply for outside the government. And while commercials persisted, there was a prevailing notion that they were doing damage to your brain. Increased media consumption would awaken something inside of you, and buying all these chemicals would damage your brain and mutate your body.

That was certainly the case with Bruce Robinson's "How to Get Ahead in Advertising," a bleak film about what happens to the mind and body of an ad exec named Denis (Richard E. Grant, seldom better) after he snaps. Denis was working on a slogan for a pimple cream when he has a nervous breakdown and has to leave the industry. This causes him to reflect on how ethical advertising it; it is, after all, an artistic form of lying. There is no art to ads, as they are tainted by their purpose. And then, in the middle of his crisis, Denis develops a boil on his neck. It grows and grows, and soon begins talking to him. It's the dark part of his soul bubbling to the surface.

Advertising is a recent development in terms of human history, but it has rewired our brains for the worse. "How to Get Ahead" examines the warping of human consciousness. It argues that the ads will win in the end, sadly, but it does endeavor to leave us thoughtful about the media that's constantly being poured into our brain cavities.

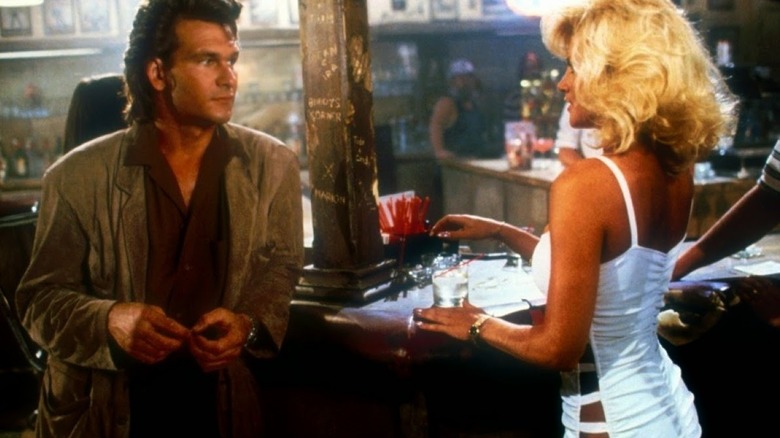

Road House (1989) is about Dalton

Sometimes philosophy comes from the least likely places. Sometimes a glorious piece of trash like Rowdy Herrington's fight-epic "Road House" can give us the strength we need to carry on. "Road House" is about an itinerant bouncer named Dalton (Patrick Swayze) who specializes in cleaning up particularly nasty bars. His Zen-like travels have brought him to the Double Deuce, an out-of-the-way rock venue in the middle of Missouri. Dalton is a strange amalgamation of constructive philosophy. He possesses the pragmatism of William James, the Stoicism of Zeno, and the inner peace of, well, Bodhidharma. He is an expert in violence, but insists that it only be used as a last resort. One's confidence and strength of character should be enough to rule over the herd. He has reached enlightenment. He is Nietzsche's Last Man. His body is a temporary vessel. Pain don't hurt.

Of course, what place does enlightenment have in a rowdy, crass, crime-riddled, sexed-up locale like the Double Deuce? Can Dalton's peaceful ways and gentle mastery of the world face off against the corruption of the local crime lord (Ben Gazzara)? And can such a figure destroy his ego enough to fall in love with a local doctor (Kelly Lynch)?

Is "Road House" a good movie? No it isn't. And somehow it's the greatest movie. It's all the life-affirming platitudes rolled into one, all as a flimsy coat over an inner ball of lascivious violence. And make no mistake, that violence is a lot of fun. "Road House" is about the ultimate conflict of id and ego in the audience. It's as goofy as we want, but as wise as we crave. It's all human contradictions all rolled into one.