How Glen Powell's Running Man Performance Breaks The Fourth Wall

This article contains spoilers for "The Running Man."

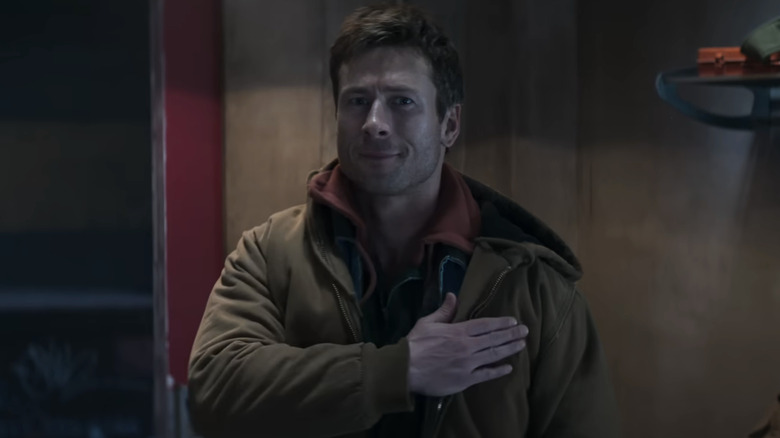

We are in the throes of the Glen Powell era, and it's never been more apparent than with the release of Edgar Wright's "The Running Man." The last few years of box office hits, Tom Cruise supporting roles, and what his former co-star Sydney Sweeney might call "good genes" have made him the heir apparent to the Four White Chrises, who have now all sadly been lost to their 40s (may they rest in peace).

That's not to cast aspersions on Powell's talent. I'd probably slot him somewhere in the middle of the Chrises, certainly over Pratt but decidedly below Pine. Rather, I'm bringing this all up because his latest movie brings it up, too. "The Running Man," like its 1987 predecessor, has a meta level to it, where the actors are both the characters and themselves. The reason Powell was cast in the film is, essentially, the same reason his character of Ben Richards, is cast on the in-world "Running Man" TV show — a combination of traits that Network producer Dan Killian (Josh Brolin) describes as "strong" and "salt-of-the-earth."

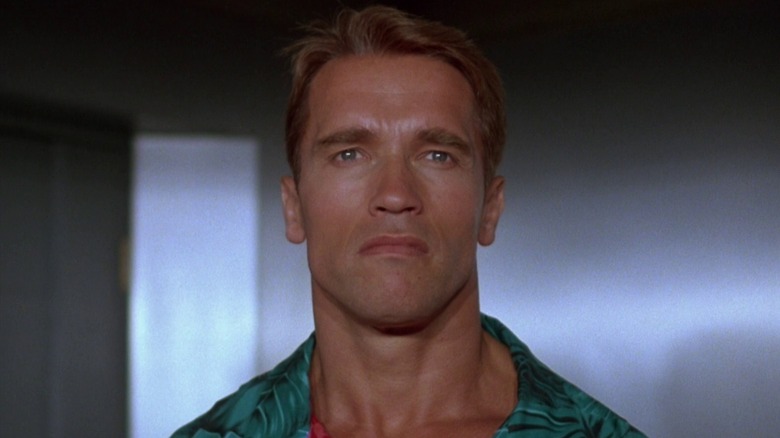

In today's world, some would probably just say "not woke." In a film that frequently runs around its obvious politics, the way Powell's casting taps on the fourth wall is particularly interesting. His starring role in the film is reflective of his Hollywood ascension and noncontroversial mass appeal — the same sort of appeal that Killian sees in Ben. And while the politics of this meta-casting are different, it harkens back to a similar aspect of Arnold Schwarzenegger's "Running Man."

The original Running Man had similar meta casting

The 1987 version of "The Running Man" is very different from both Edgar Wright's film and Stephen King's novel (as Wright set out to make a much more faithful adaptation). America is more of a paramilitary dictatorship than a technofascist capitalism; the game itself takes place in an enclosed arena, rather than the "real world," and Schwarzenegger's character is a former cop framed for murdering civilians when he refused orders to do so, rather than a regular citizen from the slums.

That last bit ends up being relevant, as Richard Dawson's Damon Killian (the original film's version of Dan Killian and Bobby T. wrapped into one) picks Ben personally after seeing him on the news. He has multiple lines referencing Ben's incredible physique, how he's made for television, and how his biceps alone will bump their ratings — references that are as much about Schwarzenegger himself as they are about his character. Both films know well what their respective audiences are looking for, and they deliver it knowingly, just as their in-universe media empires do.

The Running Man and the everyman

Schwarzenegger was the star of his day — a larger-than-life figure in an era when bodybuilding and professional wrestling had a chokehold on Hollywood masculinity. Powell is a much better fit for 2025. Though he's jacked beyond measure here, his character retains a kind of everyman relatability. Or at least, that's certainly the goal.

At the end of "The Running Man," Ben survives a daring escape from the Network jet he hijacks, but he doesn't proclaim his survival for the world to hear. That's probably because he wants safety and anonymity for his wife and daughter, but the film doesn't let Ben tell us for himself. He participates in an armed insurrection in the final scene, but as a masked militant, blending in with the others around him. This is very different from the similar scene at the end of 1987's "The Running Man," where Schwarzenegger's Ben leads the attack personally, providing leadership to a group of inexperienced "kids."

Is this a clever commentary about how, for us "everymen," it's communal effort, not individual heroism, that will ultimately triumph? Sadly, I think I'm stretching too far to get there. Edgar Wright's film doesn't linger on its politics, and it seems almost afraid of engaging with Ben's final form as a full-blown revolutionary. But hey, maybe that's just part of the meta-narrative. Neither Glen Powell nor Ben Richards can afford to be too controversial, after all.