15 Best Campy Horror Movies Of All Time, Ranked

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Defined by the great Susan Sontag in her 1964 essay "Notes on Camp" as "a vision of the world in terms of style — but a particular kind of style [defined by] the love of the exaggerated, the 'off,' of things-being-what-they-are-not," the camp sensibility is among the most captivating vibrations of the entire post-industrial art canon, and it occupies an especially conspicuous place in cinema.

Horror cinema, in particular, with its intrinsic love of irrationality and macabre excess, has a lot of love for the expansive possibilities of camp — whether manifested in bizarre tonal trapeze acts, decadent spectacles of color and fashion, spoofs that have their cake and eat it, or ribald erotic freakouts. This list of the greatest campy horror movies offers a compendium of camp's varied meanings, but not an exhaustive one; after all, the sky is the limit when you aren't bound by good taste.

15. Vamp

Richard Wenk's 1986 midnight classic "Vamp" is a cauldron bubbling with some of the most reliable ingredients of a great camp horror flick: A college milieu, a homoerotic frat bro friendship, a single-night timeframe, a strip club, a sense of humor bordering on corny, and an utter lack of seriousness. And, tying it all together, one of the greatest assets any horror movie has ever boasted: Grace Jones, in full body paint designed by Keith Haring, playing a hypnotic seductress who transforms into a sharp-toothed vampire beast.

The story concerns two college friends (Chris Makepeace and Robert Rusler) who set out to hire a stripper to gain favor with a fraternity they're desperate to enter; their quest leads them to Katrina (Jones), a singularly expressive stripper at a shady club. Soon enough, the boys find themselves surrounded by bloodthirsty vamps. As will be the case with many films on this list, however, the plot scarcely matters; it's all about the sheer garish fun, the delicious neon photography, the wholly unserious college comedy, and Grace, Grace, Grace, setting the screen ablaze in a role nobody else could have played.

14. Psycho Beach Party

It's not often that a modern-day horror movie actively endeavors to become a hysterical camp classic and actually succeeds; that strategy more often than not leads to unfun slogs that never shake off the feeling of trying too hard. And, to be sure, 2000's "Psycho Beach Party" tries very, very hard. But somehow, by force of the joy it takes in its own mess, this Robert Lee King-directed half "Gidget"-spoof-half-straightforward teen slasher manages to be exactly the unqualified hoot it wants to be.

A pre-"Six Feet Under" Lauren Ambrose stars as perky tomboy Florence "Chicklet" Forrest, who yearns to get in with the popular surfer kids of Malibu. Soon, however, she begins to lose her grip on reality and develop multiple disparate personalities — one of which may be the killer responsible for an ongoing series of grisly murders. It's all ridiculous, of course, in keeping with the pseudo-psychiatric '50s chillers that the movie is referencing — but the mélange of stylized horror, hearty emotional histrionics, queer subversion, and hilariously inane beach-movie antics (complete with an early Amy Adams performance that slots right alongside her memorable roles on "Buffy" and "Charmed") ultimately proves impossible to resist.

13. Blood Bath

With an eye for camp's possibilities, the greatness of a movie can lie not in what went precisely right during its production, but in what went wrong. Take 1966's "Blood Bath." Commissioned by Roger Corman, the indie cinema godfather, as an attempted revamp of an unreleasable Yugoslavian spy thriller, the film initially fell into the hands of director Jack Hill. By adding several new scenes, Hill transformed the original material into a horror flick about a serial-killing artist who paints his dead victims. Still unsatisfied, Corman hired Stephanie Rothman for yet more reshoots, and she added a vampirism element.

The result of all that turbulence is a fascinating patchwork quilt of a movie, which combines the highly distinct sensibilities of Hill and Rothman into a hectic, grotesque, incongruent, and yet somehow artistically and thematically coherent study of art, exploitation, and the male gaze. It's a movie that finds two great genre filmmakers bumping, intentionally or not, into a prototype of philosophically charged Euro arthouse horror — and doing it all within the grimy halls of American B-movie cinema.

12. Killed the Family and Went to the Movies (1991)

In 1969, Brazilian maverick Júlio Bressane — an exponent of the "Marginal Cinema" movement, which existed in stark conceptual opposition to the more respectable Brazilian New Wave — made "Killed the Family and Went to the Movies," a structural, highly intellectualized exercise in cinematic rule-bending. Then, in 1991, "Killed the Family..." got remade in a vastly different historical context by a different kind of maverick director: Neville d'Almeida, a luminary of the trashy and enormously successful Brazilian softcore comedy genre pornochanchada.

Working off of a decade of tussles between artistic animus, establishment taste, and popular interest in Brazil's audiovisual production, d'Almeida re-envisioned Bressane's story of surreal horror sparked by a brutal urban crime into a cackling burlesque. True to the title, a young man (Alexandre Frota) kills his family and goes to the movies, where he watches a series of vignettes about love, lust, and violence that teem with the high-low tensions of '80s Latin American soap operas. It's the kind of movie that leaves you in disbelief at what you're watching — a deceptively ridiculous riot that knows exactly what it's doing at every turn.

11. Tenement

Among the many varieties of exploitation cinema produced around the world in the '70s and '80s, American exploitation flicks have a particular paradoxical poignancy — a proximity to the ritz and respectability of Hollywood, and a symbiotic relationship with its established genre codes, that further emphasize the remove at which the seedy underbelly exists. The best exploitation filmmakers understood that remove as a liberatory force, and that was very much the case of Roberta Findlay, whose camp-classic films throb with the fears and taboos that every American wrestled with and no American dared talk about.

Of the various Findlay-directed horror movies you'd never want to watch around your parents, 1985's "Tenement" is a highlight. Following 24 hours of bloody conflict between the tenants of a Bronx apartment complex and an encroaching street gang with designs on taking over the building, the film manifests the subliminal anxieties common to the era's "gang films" with a revelatory amorality. There are no good guys, yet every person on screen is imbued with a strange, aching dignity for being at the receiving end of such societal indifference — which only makes the relentless barrage of brutality all the punchier.

10. Jennifer's Body

In Karyn Kusama's "Jennifer's Body," it's not so much that hell is a teenage girl, but that being a teenage girl in the world that we have is seeing the face of the devil. One of the most misunderstood films of the 21st century upon its original release, "Jennifer's Body" was marketed by 20th Century Fox to the very horned-up, objectification-prone bros it was critiquing; as a result, it took years for Kusama's saga of anguished adolescent comeuppance to reach its intended audience.

That "Jennifer's Body" then near-immediately became a true cult classic is a testament to the way its main creative forces — Kusama, writer Diablo Cody, and stars Megan Fox and Amanda Seyfried in career-best form — harmonized its disparate parts into an unforgettably nasty whole. Disrupted small-town idyl, rape-revenge subversion, post-9/11 melancholia, codependent teen girl friendship, and trademark Diablo Cody verbal absurdity all come together in a reverential yet deeply singular story about a high school murder victim (Fox) who comes back to life as a man-devouring succubus. It's perfect viewing for a sleepover and a film studies class alike.

9. Muscle

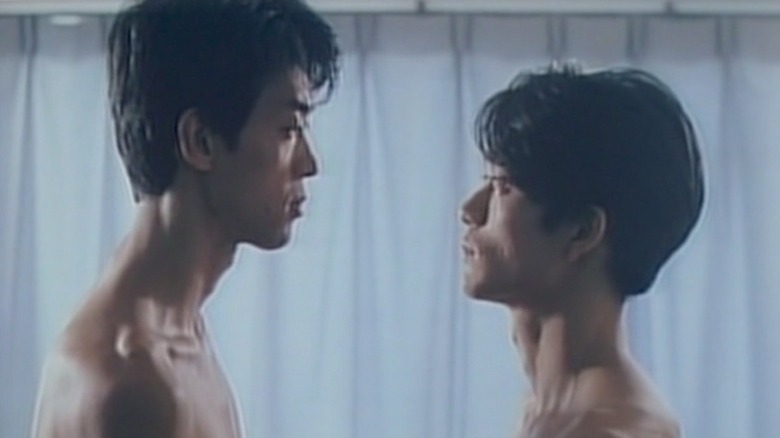

From shrieking splatter flicks to ambitious arthouse concoctions to expectation-twisting exercises in would-be pornography, pinku eiga master Hisayasu Satō did it all. In the pantheon of underground Japanese filmmakers who specialized in the erotic (and in the avenues for unencumbered expression it offered), Satō is especially notable for having brought queer themes and interests into the fold — as demonstrated by 1989's "Muscle," arguably his most accomplished and interesting film.

Sometimes alternatively titled "Mad Ballroom Gala," "Muscle" follows Ryuzaki (Takeshi Itō), a beefcake magazine editor who begins a charged romantic and sexual relationship with Kitami (Simon Kumai). Over time, the two men lock into a sadomasochistic dynamic so extreme and ravenous that it leaves the realm of mere kinkiness and leads to grisly, horrific, mutually destructive consequences. Through their sweaty and blood-soaked dance, Satō lays bare a theory of desire as atavistic consumption, offering up images so jaw-dropping and over-the-top in their blunt corporeality that they whisk you off into a waking nightmare — from which you, somehow, don't want to wake up.

8. Blood Diner

The thing about a movie like 1987's "Blood Diner" is that it's no more preposterous or gruesome than the world in which it exists; it's just more honest about it. Sure, the idea of a rundown diner's owners picking out young women from their clientele and slaughtering them to add their body parts to a special cannibalistic feast may sound outlandish on its face. But, in all honesty, is it really that far off from the way capitalist society operates and justifies itself — in the '80s, no less?

The big fictional distinction is that, in "Blood Diner," the deity Michael (Rick Burks) and George Tutman (Carl Crew) are worshipping is not a bottom line or a stock exchange but Sheetar, a literal ancient deity from the fictional continent of Lemuria. Brainwashed by their serial killer uncle (presented as a brain in a jar voiced by Drew Godderis) into stitching together a sacrifice for Sheetar, the brothers bumble their way through the world's most ridiculous murder spree, which director Jackie Kong renders with endless gory gusto, a deliciously bonkers sense of humor, and John Waters-esque savviness to the fact that the real world is the real farce.

7. A Lizard in a Woman's Skin

There's a particular flavor of campiness that can only be found in the best giallo films, and it's closer to what a student of the style might call high camp — camp as a rarefied level of extravagance, of splendor and beauty given the liberty to become massive, while still retaining a fundamental playfulness. Lucio Fulci's "A Lizard in a Woman's Skin" is one of the campiest of all giallo films, as well as one of the highest: It never quite feels as though it takes place in the real world, and yet its appeal to the senses and to the subconscious is as materially intoxicating as cinema gets.

Fulci avails himself freely and gleefully of early-seventies psychedelia in his telling of the story of Carol Hammond (Florinda Bolkan), who begins to experience chillingly tactile nightmares about LSD-fueled bacchanals. As the nightmares turn violent, Carol suddenly finds the line between dream and reality to be irrevocably blurred: Her neighbor Julia (Anita Strindberg) has been murdered, and she has no idea if she's the culprit. As Carol slips into insanity, Fulci presses further and further into a flurry of gaudy chiaroscuro images, all statuesquely beautiful, each one more deranged and mind-melting than the last.

6. Blood and Black Lace

The aesthetic of Mario Bava's "Blood and Black Lace" is so overwhelming that it feels illegal. "Wait, movies can do that much?" you find yourself wondering as Bava inundates the screen with shades of red, blue, and pink that he appears to have pulled from some previously inaccessible ether. From the movie's 1964 release onwards, practitioners and imitators of giallo spent decades replicating its proposition of a cinema unencumbered by dramaturgy, yet no reiteration ever matched the sheer purity of the original.

There's a story, sure — a masked killer starts killing the models of a Roman fashion house one by one — but good luck following it, or even remembering it's there: In its parade through show-stopping horror setpieces in haute couture, with a rotating ensemble of near-identical actresses as the ushers, this is a movie that defies object permanence. If you give yourself over fully, it's one of horror cinema's most thrilling, inexplicable, and invigoratingly senseless experiences ever.

5. Helter Skelter

Leave it to the 21st century's foremost practitioner of candy-colored nature photography to create a horror film that feels like being trapped in a bed of poisonous flowers. An adaptation of the eponymous manga by Kyoko Okazaki, 2012's "Helter Skelter" finds Mika Ninagawa reaching, in her second outing as a feature film director, the pinnacle of her filmmaking style — defined, here more than ever, by plastic beauty exaggerated to the point of madness.

In the story, adapted from the manga by screenwriter Arisa Kaneko, supermodel Lilico Hirukoma (Erika Sawajiri) has just undergone a series of full-body cosmetic procedures with the aim of attaining the "perfect" physical appearance. Before she's even had time to settle into her dream figure, however, Lilico begins to experience terrifying side effects that turn her dream into a nightmare. Besieged on all sides by sycophants who only care about her image, Lilico finds herself all alone in a twisted body horror fable; her only ally is Ninagawa herself, who explodes the story's thematic tensions into a million shards of color and texture while keeping a tight focus on her protagonist's overlooked, unraveling humanity.

4. Slumber Party Massacre II

From 1982 to 1990, the original "Slumber Party Massacre" trilogy offered up successive slidings of campy pleasure, with a row of female-directed films that took boilerplate-seeming slasher setups and made them into unlikely triumphs of nerve and imagination. There's a lot of debate among horror fans as to whether Amy Jones' "The Slumber Party Massacre" or Deborah Brock's "Slumber Party Massacre II" is the best of the bunch, but, if we're talking camp, there's no beating the one that doubles as a rock musical and features an electric guitar fitted with a drill bit as the primary murder weapon.

In addition to rewriting the language of the slasher horror film, with even the seemingly kitschy musical tone being eventually destabilized by a proto-Lynchian emphasis on the existential trappings of suburbia, 1987's "Slumber Party Massacre II" is just about as gloriously brash, dizzyingly silly yet serious, disarmingly idea-strewn, and unapologetically '80s as horror movies get. As for Brock's visual conception of its teenage protagonists' world as a fluffy cloud of bright pink cotton, it's pretty much "A Nightmare on Elm Street" if it got a little girlier — which is to say, a marvel.

3. What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?

Consider the scene-setting: Bette Davis and Joan Crawford, two crepuscular legends of Golden Age Hollywood, spring for a project that might once have been thought of as beneath them, yet for which they aren't even considered bankable enough. The project in question, a trashy psycho-biddy chiller directed by Robert Aldrich from a horror novel by Henry Farrell, gleefully incorporates its stars' fraught offscreen history, stirs it up into a meta-stew of melodrama and black comedy, steadfastly refuses to commit to a tone, and ratchets things up with enough violence and tastelessness to land it an X rating in the U.K.

What is to be made of it? Nobody knows; despite a massive studio pedigree, the Oscars mostly give it the cold shoulder, and instead nominate the "Mutiny on the Bounty" remake or whatever; critics, entertained but alarmed, struggle to reach a consensus. Then, years pass, and the true enormity of "What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?" reveals itself, gradually, in the innumerable references of artists, filmmakers, and queer fans who have since had its freaky segues imprinted into their subconscious, for reasons that sidestep rhetorical explanation. This is what camp is.

2. Bride of Frankenstein

Elsa Lanchester's performance as the Monster's Mate in "Bride of Frankenstein" is not just a foundation of camp horror, but a foundation of everything we conceive of as camp. Every auteurist analysis of James Whale's work as a pioneering gay filmmaker begins with the iconic side profile view of Lanchester in her white-streaked Bride wig, from which she then darts her head about like a bird on alert, ultimately turning directly towards the camera. In just three minutes of screentime counted from her climactic creation, Lanchester captures, with balletic perfection, the essence of the Monster as a metaphor for ostracized queerness.

That appearance is the heart of "Bride of Frankenstein," but everything around Lanchester in the 1935 film teems with similar purposefulness. If the first installment was beautiful and tragic enough in its evocation of the Monster's (Boris Karloff) misunderstood innocence, "Bride of Frankenstein" sends every emotion into such overdrive that it's a miracle the movie ever made it past the censors. The Gothic cinematography, dark humor, and lurid maximalism become a paean to the very importance of strangeness: If no normal person could have possibly made this film, what's the use in being normal?

1. House

From its to-the-point yet bizarrely inert title, "House" announces itself as a movie that cannot be understood or assailed, that simply is, and must be accepted as such. Developed largely from the ideas of Chigumi Obayashi, the preteen daughter of director Nobuhiko Obayashi, it's a beautiful, bizarre blockbuster that moves from one moment to the next in the liberated manner of a child inventing a story on the fly — and reaches into deep, primal reserves of horror for much the same reason.

The miracle, here, is that the horror gets to be that persuasive without once contradicting the reigning goofiness. Released in 1977, "House" tells the story of a schoolgirl (Kimiko Ikegami) who takes her friends on a trip to the country home of her aunt (Yōko Minamida), only for the house to start devouring each girl in increasingly surreal, absurd, medium-bending ways — and every step in the escalation of the close-quarters mayhem of "House" manages to combine silly gags and guttural panic into a cohesive, indivisible unit. It's not a horror comedy, but a secret third thing, funny because it's scary and scary because it's funny. In short: It's camp.