5 Essential Star Trek: The Original Series Episodes That Everyone Should Watch At Least Once

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

It's important to note that "essential" episodes of "Star Trek" are not necessarily the best ones. To this author, "essential" denotes episodes that are wholly emblematic of the series at large, episodes that boast stories and concepts that are unique to the show or at least represent its tone and philosophies best.

Most Trekkies, for instance, tell you that "Amok Time" (September 15, 1967) is one of the best episodes of the series since it explores the inner life of Spock (Leonard Nimoy), his elaborate mating customs, and the Vulcan homeworld. The quality of that episode, however, is going to be contingent on how much you know (and presumably like) Spock going in. If "Amok Time" is the first "Star Trek" episode you ever see, you may not necessarily appreciate the relationship Spock has with Captain Kirk (William Shatner).

Ditto "The City on the Edge of Forever" (April 6, 1967). In that episode, Kirk and Spock — via a sentient time portal — travel back in time to the year 1930. There, they find a stalwart social worker named Edith Keeler (Joan Collins), whose talk of togetherness and peace may spell out a brighter future for humankind than the one it is about to face in World War II. Sadly, Spock and Kirk find that, in a butterfly effect fashion, Edith has to die for the Allied armies to go on to victory. This is a problem because Kirk has fallen in love. It's a brilliant sci-fi story, but it would have played just as well as an episode of "The Twilight Zone." Indeed, Kirk and Spock should have found ways to rescue Edith; they're smart lads.

These episodes, while perhaps the best, don't necessarily communicate what "Star Trek" is all about. These are exceptions, not rules. The five episodes listed below in no particular order, however, all possess the concepts, stories, character moments, and silliness that "Star Trek" has come to be known for.

The Corbomite Maneuver

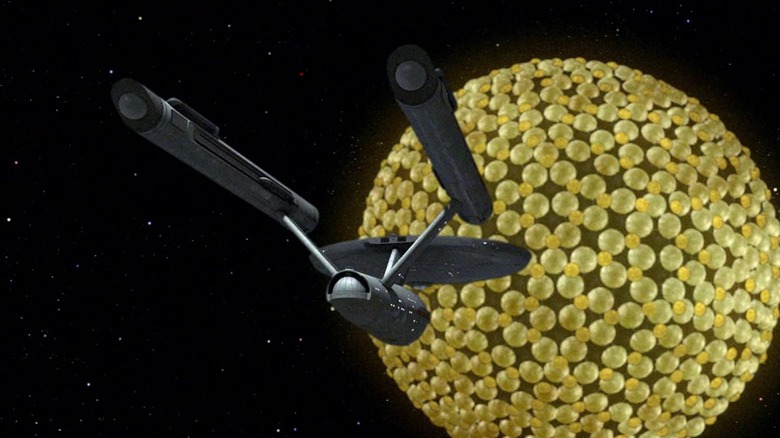

One of the very first episodes of "Star Trek," "The Corbomite Maneuver" (November 10, 1966), depicts the U.S.S. Enterprise encountering something truly unknown, ineffably powerful, and potentially deadly. While out in the outer reaches of space, they meet the Fesarius, an enormous spherical ship of unknown origin. They are audio-hailed by the ship's captain, Balok (voice of Ted Cassidy), who instructs the crew that he's going to blow up the Enterprise in 10 minutes as a punishment for exploding one of his deadly probes. Spock manages to get a visual of Balok, and he's a scary, frowning monster.

Kirk, thinking quickly, bluffs. He tells Balok that the Enterprise is equipped with a powerful element called "corbomite," which is designed to reflect enemy attacks back at them. Yes, Kirk says, the Enterprise may be destroyed, but so too the Fesarius. This bluff causes Balok to delay his attack. The bulk of the episode is a tense face-off between the two captains. By the end of the episode, Kirk and co. learn that Balok is not a scary, violent attacker. Indeed, the Balok they saw on their screens was a mannequin, and the real Balok is a hyperintelligent child played by Clint Howard. He isn't interested in killing anyone, but does want to test the Enterprise to make sure it isn't dangerous. Really, he just wants to learn about humanity and engage in a cultural exchange.

"The Corbomite Maneuver" is classic Trek in both concept and character. It shows that there are ultra-powerful forces beyond our comprehension out in the cosmos, that Kirk is a fast-thinking captain, and that he can, with his wits, bluff his way out of a tense situation. At the end of the day, it shows that there are no violent attackers or monsters, but fellow curious souls who are just as suspicious of us as we are of them.

Shore Leave

"Star Trek" is certainly known for being silly, and "Shore Leave" (December 29, 1966) may be one of the show's sillier episodes. The senior staff of the Enterprise, looking to take a short vacation, beam down to a peaceful, verdant planet, thinking it would be suitable for a break. They find, however, that their merry, idle thoughts are inexplicably manifesting physically. Dr. McCoy (DeForest Kelley) imagines the White Rabbit from "Alice's Adventures in Wonderland," and lo, he sees the very rabbit in question. Sulu (George Takei) dreams about the history of firearms, and an old fashioned handgun appears under a nearby rock. Kirk dreams of an old school rival named Finnegan (Bruce Mars), and he appears out of thin air (and still wants to fight).

The ultimate explanation is that this world is actually a covert resort planet. It employs mind-reading technology and an android-manufacturing device to provide its denizens with whatever they might want — just be careful what you think about. This is a farfetched explanation, even among the fantastical technologies seen on "Star Trek." More than anything, it's an excuse to provide the spacebound series with some visual variety: The episode filmed on location at a theme park in Redwood City, California, and it looks like it. The Starfleet uniforms look whimsically out of place next to a real-life park.

"Shore Leave" is emblematic of "Star Trek" in this regard, though. Throughout the franchise, writers have revisited, time and again, the notion of fantasies made manifest. Starfleet officers, while serious, job-oriented characters, still dream of kid's novels, knight fantasies, and besting their old school rivals. We may be living in a high-tech utopia in "Star Trek," but we're mercifully still prone to fantasies.

The Ultimate Computer

Part of the utopia of "Star Trek" is that humans finally use technology to positive ends. Because it's a post-capitalist future, inventors turn to making miracle technologies that serve primarily to benefit humankind. We have faster-than-light engines, but use them to explore, deliver medicine, reallocate resources, and deliver diplomats. Food replicators have served to eliminate want and computers are ultra-powerful super-brains that aid these goals. The lesson of "Star Trek" is that we're capable of inventing great machines — provided we're wary of how they're used.

That's the theme of "The Ultimate Computer" (March 8, 1968), an episode that sees the ambitious computer scientist Dr. Daystrom (William Marshall) testing out a new computer system that is faster and better than any human starship crew. The computer is tested on the Enterprise, and Daystrom is pleased to see that it can make decisions logically and quickly. There is even a moment where Kirk fears that his job may be supplanted by a computer.

Of course, there is a flaw in the system. Daystrom reveals that he used his own brain engrams to program the computer, and sees that it's beginning to reflect his deep-seated career anxieties. The computer itself becomes insecure and defensive. Our technology cannot be better than us; it can only reflect who we are. The computer begins defending itself from Enterprise remembers who seek to shut it off, and it even deliberately murders someone. Kirk has to use his very biological intuition to outsmart the machine.

This isn't a cautionary tale about fearing technology, though. "Star Trek" is all about technology, and the characters interact with ineffable machines as part of their daily job. Instead, "The Ultimate Computer" highlights the very "Star Trek" notion that the function of tech is to help us learn, grow, and commit acts of benevolence — not to replace us. If we attempt replacing ourselves, we only end up revealing our inner darkness. For a real-life example of this, see when generative A.I. reflects fascist ideas.

The Trouble with Tribbles

"The Trouble with Tribbles" (December 29, 1967) is a comedy episode about fast-reproducing living furballs — the titular tribbles — and the havoc they wreak on a distant space station. While there are giggles to be had over watching the normally stalwart crew of the Enterprise getting cuted out by the critters, there's something more salient happening. "The Trouble with Tribbles" is actually one of the only original "Star Trek" episodes to deal with the vital mechanics of resource allocation.

The space station in question is loaded up with an artificial grain called quadrotriticale, which is desperately needed by many space colonies if they are to survive. Kirk, an adventurer, is asked to guard the grain, a job he considers beneath him. Kirk may be bored by the idea of guarding a grain locker, but "Trouble with Tribbles" does denote that it's vitally important to the "Star Trek" universe. Not all of Starfleet's assignments are sexy, but they're all necessary. What happens when vermin — the tribbles — invade this grain supply? Devastation. The tribbles are goofy little monsters, but they're a threat. Also, there are Klingons on the station, and the administrators (represented by William Schallert) are not sure what their intentions might be. Are they, too, a threat to the supply chain?

Nerds like me revel in the fact that "Star Trek" is based on a massively complex bureaucracy. The paperwork, petty jobs, and dull maintanence are vital parts of a utopia, and it requires a lot of hard work and attention to detail in order to function. "The Trouble with Tribbles" reveals that boring crap, including artificial grain, is just as important as surfing black holes.

The Cage

Early in its run, "Star Trek" was more of a horror show than a sci-fi series. The first season contains multiple monster-of-the-week episodes, and crew members of the Enterprise frequently die in horrible ways. One could have their salt extracted by a psychic salt vampire, or their face might be magically removed by a capricious god-child. The universe is unknowable and it's populated by beasts.

That tone overrides the original "Star Trek" pilot, "The Cage." "The Cage" is similar in concept to the "Star Trek" audiences eventually saw, but it features an entirely different cast (save for Leonard Nimoy as Spock). Kirk is preceded by Captain Pike (Jeffrey Hunter), an angrier, more confrontational character. In the pilot, Pike is captured by eerie big-headed Talosians who keep him captive in a zoo-like enclosure and use their psychic powers to create elaborate fantasies for him. The fantasies are used as rewards or punishments, depending on the Talosians' whims. Pike uses his anger at being forcibly incarcerated to fight their psychic intrusions.

"The Cage" is essential in showing the premise of "Star Trek," even if it wasn't polished yet. The future is run by a benevolent military organization and space is full of strange psychic monsters. "The Cage" didn't air to the public until 1988, although it has since been welcomed into "Star Trek" canon as having taken place before the first Kirk episodes. Indeed, "Star Trek: Strange New Worlds" is directly extrapolated from "The Cage" and stars Anson Mount as Captain Pike.

"The Cage" is a marvelous example of how Trekkies came to form the earliest notions of sci-fi TV canon, able to easily connect the events of "The Cage" with "Star Trek" at large. These days, it's easily accepted that disparate sci-fi shows and movies can be part of the same overarching supernarrative. Back in 1966, it took some imagination to canonically explain NBC's studio notes and a massive rewrite to "Star Trek," but Trekkies had the imagination.