The Prince Of Egypt Exists Because Of One Key Steven Spielberg Suggestion

Animation had a wild year in 1998. Disney released the action-packed musical "Mulan," which broke new ground in terms of Asian American representation in animation. Meanwhile, Pixar followed up "Toy Story" with "A Bug's Life" and showed CGI animation was (for better and worse) here to stay, even as"Pokémon: The First Movie" took Pokémania to new heights and broke box office records. Most importantly, it was the year when Disney's domination over the American animation landscape truly started to crumble, with three different studios making their feature animation debuts that year: Nickelodeon with "The Rugrats Movie," Warner Bros. Feature Animation with "Quest for Camelot," and DreamWorks Animation with both "Antz" (its answer to "A Bug's Life") and "The Prince of Egypt."

That last bit is especially important. While Nickelodeon Movies didn't stick to theatrical features for very long (with the exception of its "SpongeBob SquarePants" sequels) and Warner Bros. Feature Animation similarly prioritized the home media market after that, DreamWorks quickly became an animation powerhouse and Disney's biggest box office (and awards) rival. What's more, although "Antz" came out first, it was "The Prince of Egypt" that made the biggest splash, winning Best Original Song at the Oscars and going on to be widely regarded as one of the best American animated movies of all time. And to think it all happened because of one suggestion from Steven Spielberg.

This story was recounted so many times in the 1990s that it became almost mythic, at least according to a 1998 piece by The Washington Post. As the tale goes, when Jeffrey Katzenberg met with Steven Spielberg and David Geffen to start the discussion that eventually led to the founding of DreamWorks SKG, the former head of Walt Disney Studios was eager to expand the range of animated films being made and make DreamWorks a true competitor to the Mouse House. Indeed, Katzenberg listed movies like "Raiders of the Lost Ark" and "The Terminator" as the kind of films that could be done in animation, seeing as the medium is all about transporting audiences to new worlds and presenting all sorts of fantastical concepts and visuals.

"I said, 'More than anything else, I'd love to do a movie that has the epic cinema and scale of my favorite movie, 'Lawrence of Arabia,' and the intimacy of what David Lean was able to do in his storytelling,'" Katzenberg recounted. "And the next words out of Steven's mouth were: 'Good, you should do 'The Ten Commandments!'"

The Prince of Egypt aspired to be a biblical epic like no other

A big part of what makes "The Prince of Egypt" such a special film is how seriously it treats its subject matter. Just like "The Hunchback of Notre Dame" remains one of the darkest and most mature Disney movies ever made, "The Prince of Egypt" similarly remains one of the best things DreamWorks has done and certainly the studio's most ambitious film. Katzenberg reportedly sought to make an animated adaptation of "The Ten Commandments" at Disney but was repeatedly turned down by then-CEO Michael Eisner due to the story's religious aspect. However, at DreamWorks and with Steven "I made the definitive Holocaust film" Spielberg on his side, Katzenberg could make an animated biblical epic in the style of the grand live-action productions of the 1950s.

"Steven had the idea, and David [Geffen] was the one who said, 'If you do it, you can't tell a fairy tale. You're going to have to go about telling this with a sense of respect and integrity that nobody's done in modern times.' That was instinctual brilliance,'" Katzenberg once told the LA Times. In order to bring the epic story to life, Katzenberg reached out to both former Walt Disney Feature Animation and Amblimation artists, ultimately assembling a crew of 350 people for the film.

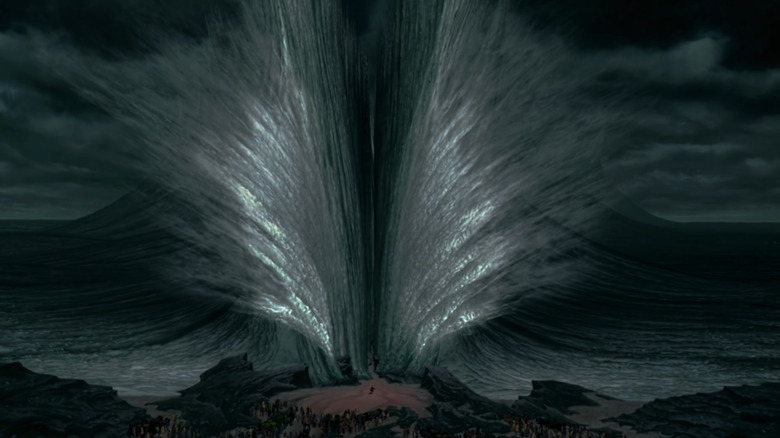

All that artistry is on display in every frame of the movie. "The Prince of Egypt" is a true epic, a film that captures the grandness of Ancient Egypt and one of the few legitimately great movies about the subject. Towering temples and monuments fill the background of almost every shot, reminding both the film's characters and the audience of this civilization's achievements without hiding the many, many enslaved people whose labor made those achievements possible. The result is not just a stunning visual accomplishment but also a phenomenal blend of traditional hand-drawn and computer animation, with the parting of the seas sequence looking better than most big-budget movies today.

The story maintains a dramatic and serious tone throughout the film's runtime as well, forgoing comedic relief and gags even when addressing the topic of infanticide. As a whole "The Prince of Egypt" felt like both the continuation of and the next step in the trend Disney had embarked upon in the mid-'90s with "Pocahontas" and the aforementioned "Hunchback of Notre Dame."

It was, in other words, a movie meant to usher a new era of animation ... except it didn't.

The Prince of Egypt should have defined DreamWorks

"The Prince of Egypt" tried to reach a wider, more adult audience. DreamWorks even avoided a marketing campaign filled with fast-food tie-ins and attached a disclaimer to the movie stating, "While artistic and historical license has been taken, we believe that this film is true to the essence, values, and integrity of a story that is a cornerstone of faith for millions of people worldwide."

Though the movie was a hit, it was meant to be more than that. In an interview with Polygon to mark the film's 20th anniversary, co-director Brenda Chapman, the first woman to direct an animated movie from a major studio, said the hope was the film would break the mold, reach an older audience, and allow DreamWorks to "bring to America all the different types [of animation]."

"How about an R-rated animated film? How about a PG-13 or an NC-17 or whatever? It's like just trying to break out of that box," Chapman added. Unfortunately, as she put it, "We didn't quite succeed."

Indeed. In the next couple of years, we would get a wave of animated movies that dared break the mold of the studio fare (read: Disney) and do different genre stories. Attempts were made with movies like "The Iron Giant," "Dinosaur," "The Road to El Dorado," "Titan A.E.," and "Atlantis: The Lost Empire." These were movies that introduced new tones, though none were as mature and serious as "The Prince of Egypt." Unfortunately, those films didn't quite hit with audiences, and studios like Disney backed down. Then came the final nail in that coffin, when "Shrek" and its Scottish accent dominated the box office, the conversation, and awards season alike, prompting DreamWorks and the entire industry to get stuck with snarky, self-aware animated comedies for a decade.