Buster Keaton's 7 Best Movies Ranked

Buster Keaton was one of the most prolific filmmakers of the silent era, comparable only to his contemporaries Charlie Chaplin and Harold Lloyd. Unlike Lloyd with his distinctive spectacles or Chaplin with his signature stache, Keaton was identified by the emotionless expression he wore while enduring some of the most painful, dangerous, and hilarious bits of physical comedy the world has ever seen.

The filmmaker grew up as a vaudeville actor and took the stage as early as age four, where he first honed his slapstick skills in an act with his father. He was always known for taking hard falls without so much as a wince, which is how he earned his nickname, Buster, as an infant. As Keaton told it, legendary illusionist Harry Houdini gave him the nickname after an infant Keaton fell down a full flight of stairs without crying (a "buster" was a slang term for a hard fall at the time).

Old Stone Face moved into filmmaking in young adulthood and quickly took to the craft. He produced several masterpieces under a contract with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, but unfortunately the the studio seized creative control in 1929 and, as cinema transitioned into talkies, Keaton's star faded. However, he experienced a career revival later in his life and became a regular on hit talk shows like "The Donna Reed Show."

Now, there's a lot of debate about which of Keaton's films is the very best, so I'm here to settle the score. I have chosen to include only his feature-length films, excluding some notable favorites like "One Week," a 20-minute "two-reeler." Although it breaks my heart to drop it from the list, I had to draw the line somewhere.

So, without further ado, here are the seven very best films from the silent era's most charming — and most tragic — figure.

7. Steamboat Bill, Jr. (1928)

Keaton is the titular character in "Steamboat Bill, Jr.," the overly-refined son of a surly sea captain who is sent to visit his father after years of being sheltered in academia. Old Stone Face takes a while to appear in this film, but when he finally does, the reveal is worth the wait. Donning a beret, a mustache, and a ukulele, he looks like the average resident of Williamsburg circa 2012. The contrast between him and his onscreen father in both height and affect is hilarious, but the joke only goes so far.

The slapstick sequences in "Steamboat Bill, Jr." are more "Mission Impossible" than they are amusing. The punchline of almost every gag is that such an effete gentleman could be an action hero, but in today's climate, it just reads as a delightfully unconventional casting choice. Of course, it wouldn't be a Keaton film without some solid slapstick moments thrown in there, although many of these were lifted from his other steamboat film, "The Navigator," which was released four years prior.

The title is a reference to the song Steamboat Bill, popularized by the folk singer Arther Collins in the 1910s. The song also inspired the cartoon popularly known as the earliest depiction of Mickey Mouse, "Steamboat Willie." The early Walt Disney animation was released six months following "Steamboat Bill, Jr." and is thought to be a parody of Keaton's film. Willie's dynamic with the gruff captain closely resembles Bill Jr.'s relationship with his father in the live-action film. Yes, Keaton's cartoonish manner was likely the direct inspiration for Mickey Mouse! So, although "Steamboat Bill, Jr." isn't my favorite of his films, it holds a significant place in cinematic history.

6. Our Hospitality (1923)

One of Keaton's oldest feature-length films, "Our Hospitality" tells a Romeo and Juliet tale that comes to a head when the son and daughter of two feuding families fall in love and the son is invited into the daughter's family home for dinner. As long as he is in the house, their family's code of honor forbids them from killing him, but certain death awaits him as soon as he steps outside. Armed with this knowledge, he attempts to extend his stay as long as possible.

"Our Hospitality" is allegedly inspired by Keaton's real-life marriage to Natalie Talmadge, who plays his love interest in the film. Talmadge came from a family of actors, just as Keaton had, and it's possible that their families were rivals on the stage. Talmadge's mother is known as the "original stage mother" and her domineering nature is well-documented. It's rumored that he found their family imposing and made this comedy to express his frustration, replacing her two nagging sisters with two murderous brothers.

As he transitioned from working only on short films of about 20 minutes in length, the silent filmmaker was still working out the balance between physical comedy and storytelling in "Our Hospitality." The exposition is quite lengthy, with a prologue that draws on far too long before we finally see Keaton on-screen.

After the long exposition, Keaton's character is launched into a long series of gags in an extended sequence on the train. The gags here are good but poorly timed, as the viewer is left waiting for the story to begin. When the characters finally reach their hometown of Rockville almost halfway into the film, things finally get interesting. The second half of the film is filled with inventive gags and compelling action sequences, it just takes a bit too long to get moving.

5. The Navigator (1924)

In his 1924 feature, Old Stone Face plays a wealthy heir who proposes unsuccessfully to the daughter of a steamboat owner and decides to attend the honeymoon he had planned without his bride. He boards the boat a night early and sleeps through a set of foreign operatives setting it adrift on the ocean, with Keaton — and the boat owner's daughter — still onboard. When they both discover each other on deck, the spoiled duo has to learn to get along and fend for themselves alone at sea.

Unlike "Our Hospitality," this film wraps up its exposition quickly. The premise is solid — solid enough that it was mirrored very closely in the 2022 Cannes Palm d'Or Winner "Triangle of Sadness." It even has an enemies-to-lovers storyline, making this the "When Harry Met Sally" of the 1920s. Additionally, there are some incredible gags making use of the steamboat's distinctive features and even an adorable kitchen sequence with a set of Rube Goldberg machines that remind me of "Chitty Chitty Bang Bang," released 48 years later.

The main problem with "The Navigator" is that it devolves into something weird and racist in the final 20 minutes. There are still some incredible comedic moments in the last act of the movie — the finale gag in particular is one of the best in the entire film — but the extensive length of the most racist bits makes the final minutes of "The Navigator" difficult to sit through.

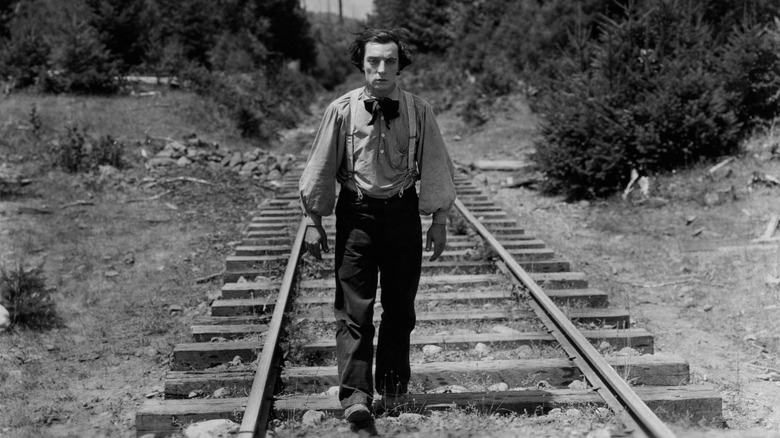

4. The General (1926)

This film is a favorite of Keaton's and was hand-picked by him for a theatrical re-release towards the end of his life, according to the documentary "A Hard Act to Follow." The comic king plays a railroad engineer who gets mixed up in the Civil War when his fianceé is mistakenly kidnapped by Union soldiers.

Much of the comedy in Keaton's films lies in the various hang-ups of the industrial era's greatest technological accomplishments, the steamboat and the train. In this way, his comedy reminds me of Jerry Seinfeld, whose jokes often centered around late 20th-century tech such as answering machines (the subject of an entire "Seinfeld" episode).

"The General" features many of the gags that Keaton became best known for and has what is perhaps the most action-packed plot of any of his films. It may be a comedy by definition, but in truth it defies genre — it has equal elements of action, romance, war, and period pieces.

The reason it doesn't rank higher on this list honestly comes down to personal preference. The romance in this film is secondary to the war and the action. Although there are some purely comedic gags, most of them are more impressive and heroic than they are humorous. Moreover, this film struggles with some of the pacing and plot issues of his earlier films, bumping it further down the list than one normally finds it.

3. Seven Chances (1925)

This true rom-com features Keaton as a young stockbroker who is hopelessly in love with the girl next door but can't bring himself to tell her. After falling on hard times in business, things start to look up when he gets word that he will inherit a large fortune from a dead relative ... if he is married by 7 o'clock that evening. When his true love rejects him, he must scramble to find a new bride and save himself and his business partner from financial disgrace.

"Seven Chances" has a perfect premise, something that you could find in a contemporary rom-com (it reminds me a little of "The Proposal" with Sandra Bullock and Ryan Reynolds). Keaton's 1925 film even invents some pretty classic gags that have found their way into basically every rom-com that followed, including one oft-imitated sequence where his love interest walks up on him while he practices his proposal.

Unlike many of the other films on this list, comedy isn't awkwardly wedged into this narrative — the story lends itself to organic comedy. It seamlessly culminates in one of the most memorable, gut-busting, and action-packed slapstick sequences of all time.

The only problem with "Seven Chances" is unfortunately a very big one, knocking it down several pegs on this list. What is otherwise a perfect film takes every available opportunity to be needlessly racist — and not in a subtle way. There is even an entire plot point that rests on the cartoonish foolishness of the girl-next-door's servant, a man in blackface. Since so many of the jokes rest on racist punchlines, it's pretty impossible to brush aside.

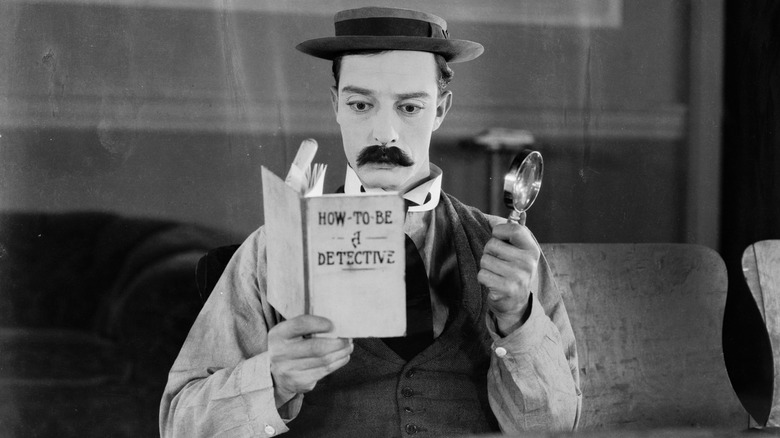

2. Sherlock Jr.

As the title implies, Keaton's 1924 film stars the filmmaker as an amateur detective who works at a movie theater for a living — reminiscent of the barista-poet archetypes one might find in any major metropolis today. When his rival in the battle for a certain young lady's affections frames him for stealing her father's watch, he must put his detective skills to the test to indict the real thief.

"Sherlock, Jr." is not the most elegantly crafted screenplay — in fact, it is the premise of two separate concepts combined, by Keaton's own admission. However, its meta exploration of cinema in its earliest days, along with unforgettable gags like Keaton's comically close pursuit of his suspect, make it one of the most frequently referenced and critically acclaimed films in his oeuvre.

The dream sequence, wherein the hapless projection operator leaps through the screen and is thrust into the world of cinema, remains one of the best montages in cinematic history. It may not fit into the plot seamlessly, but the diversion is more than worth it.

Despite the hodgepodge narrative, the resolution is gratifying. Moreover, it combines two of my favorite subjects of all time — murder and meta-cinema — earning it a potentially biased bump in the rankings.

1. The Cameraman

Keaton's 1928 film was his last with full creative control, but upon watching "The Cameraman," it's almost impossible to see why it might have lost producers' faith in him. Stone Face stars as a poor street photographer who decides to become an MGM newsreel man to impress the studio's secretary. Unfortunately, he is competing for her with an arrogant newsreel photographer who stands at almost twice his height.

Much like "Seven Chances," the premise and flow of the narrative have the feel of a contemporary rom-com. This film finds joy in its perfectly-timed diversions, like the unforgettable sequences at the public pool or the apparent death of a dancing monkey, but it also keeps the story chugging along at an excellent pace. The audience is held in suspense until the very last moment.

By 1928, Keaton had completely embodied his caricature of a romantic fool, and it permeated through every aspect of his physicality — from the expression he wore to the way he held his hands. I am filled with compassion for his character and hopelessly charmed by his clumsiness. I also find him extremely handsome, but that's another story. The only problem I have with this movie is the way that Keaton's love interest strings him along — when his character seems to fail, she is quick to leave him for the attractive antagonist. But, of course, this only speaks to Keaton's ability to solicit sympathy without saying a word. In this way, the thing that I most dislike about "The Cameraman" is one of the very things that makes it his greatest film of all.