Disney's Steamboat Willie Didn't Just Revolutionize Mickey Mouse — It Revolutionized Cartoons

(Welcome to 100 Years of Disney Magic, a series examining the history, achievements, and legacy of Disney Studios over the last century. Part 3, "Walt Disney Hits The Jackpot With Oswald The Lucky Rabbit" summarized the dramatic rise and fall of Disney's first hit. In Part 4, we look at the creation of an even bigger icon: Mickey Mouse.)

On February 15, Disney100: The Exhibition — the celebration of The Walt Disney Company's history at the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia — debuted a lifelike hologram of Walt Disney, fittingly brought to life by none other than Sorcerer Mickey. The video was shared by the D23 Twitter account. Social media took note: Some users made comparisons to imagineers famously "reanimating" assassinated president Abraham Lincoln at the 1964 New York World's Fair; others made jokes about Walt Disney's allegedly frozen corpse (untrue, by the way). The point is, most people respond by focusing on the hyper-realistic depiction of Uncle Walt — impressive regardless of how uncanny it may or may not be. I personally find it unnerving — he's too snappy and happy, like a pod person pretending to be an old man without knowing what arthritis is.

I'm far more interested in the overlooked beginning of the video with Sorcerer Mickey. The character first appeared in the 1940 commercial failure "Fantasia." The third feature film from Walt Disney Studio was highly ambitious, experimental, and expensive — and thanks to World War II (and other factors that I'll get into in a later article) did not make back nearly enough to cover its costs until many many years later. Regardless, I find it telling that of all the framing devices that could have been used to unveil the Disney100 hologram, we get Sorcerer Mickey literally conjuring up the image of his "pal."

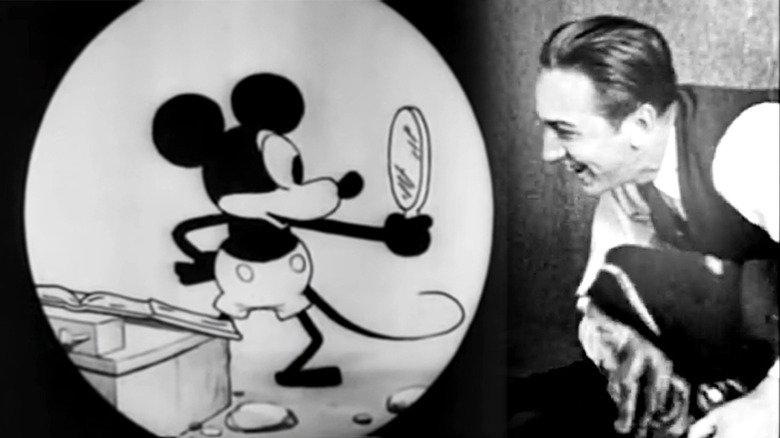

Walt Disney and Mickey Mouse: Two of a kind

I can appreciate that the creative thought process involved with the development of the Uncle Walt Disney100 hologram was probably as basic as, "hey, we have this clip of Walt talking about the company's pursuit of innovation and creativity — what if we went with a 'magic' theme? That's like our thing!" And to be clear, I do think it makes sense: seeing such a life-like, three-dimensional rendering of someone who died before "DiscoVision" existed does feel kind of other-worldly.

At the same time, the short clip accidentally makes a very apt commentary on Walt Disney as a public icon being created by Mickey Mouse.

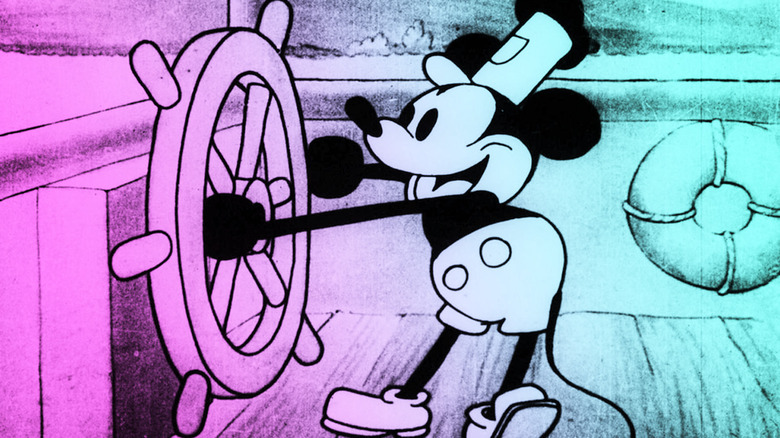

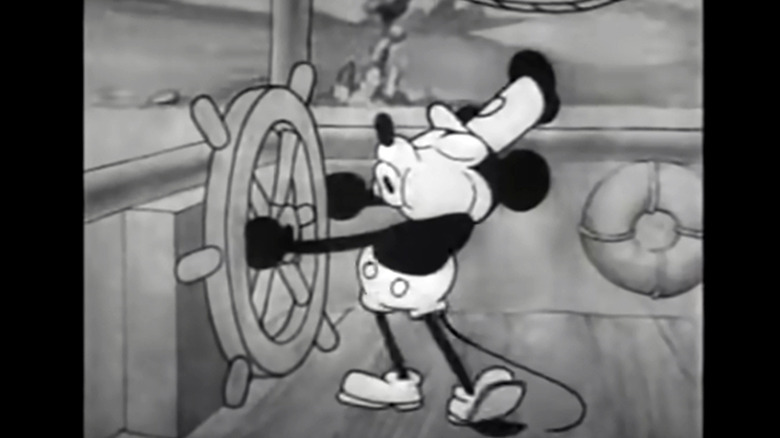

Walt Disney, especially his "Uncle Walt" persona, is intrinsically tied to the cartoon rodent who started it all. In 1928, just a year after creating and then losing the successful Oswald the Lucky Rabbit series, Walt Disney Studio released the history-making animated film "Steamboat Willie," named after one of the songs it featured, "Steamboat Bill." It was not the first cartoon to use sound — it was not even the first short to feature Mickey — but it was groundbreaking nonetheless, and that steamboat set lil' ol' Mickey on a voyage of a lifetime. He appeared in several more popular black-and-white shorts throughout the '20s and '30s until his technicolor debut, "The Band Concert" in 1935 (considered one of the best cartoons ever made, period), and then his aforementioned feature-film debut in 1940's "Fantasia." He would only get bigger from there.

Walt Disney became the face of his company, but really, Mickey Mouse was the brand. Even after 100 years in existence, no symbol captures the essence of the Walt Disney Company quite like Mickey Mouse.

How Walt Disney created Mickey Mouse

When Walt Disney went to New York to discuss his Oswald the Lucky Rabbit contract with Charles Mintz in 1927, he was confident. As Neal Gabler writes in his biography "Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination," Walt even brought his wife Lillian along for the trip, hoping to enjoy a "second honeymoon." As we learned last week, however, those negotiations were disastrous for the young businessman: not only did he fail to get the increased budget he was hoping for, but he lost the project entirely and failed to land any other business deals — despite New York City being the capital of cartoons. Universal's hit Oswald series would continue on without Walt Disney Studios, being produced in-house by Winkler Pictures — and to add insult to injury, Mintz's company was staffed with animators he'd poached from Walt.

Riding home with Lillian on his preferred mode of travel — the train — Disney must have felt gutted. His big trip to New York was a bust. He was facing his third major setback since launching his Laugh-O-gram animation studio in 1921. His first taste of real, meaningful success had lasted just a year before he lost control of the hit character he created. Here he was with his wife, heading back to a home he had just bought, facing an uncertain future. His studio had everything riding on the Oswalds. Yet, Walt refused to return empty-handed; he was nothing if not determined. By the time he landed in Los Angeles, he had a brand new character to unleash on the masses: Mickey Mouse.

Or at least, that's one version of the story.

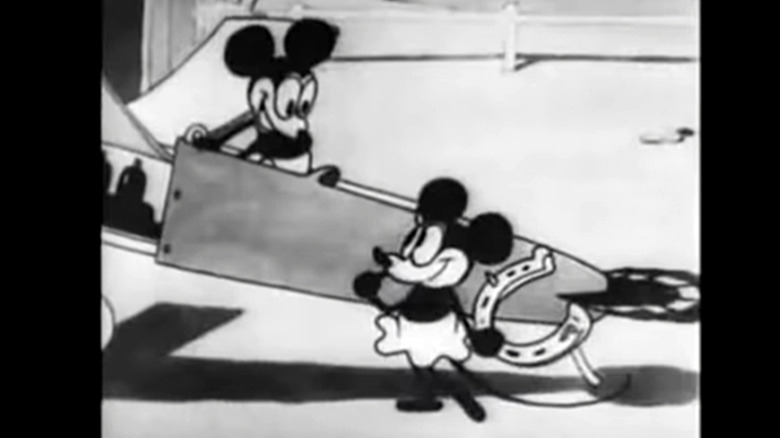

Mickey Mouse: A rodent of contested birth

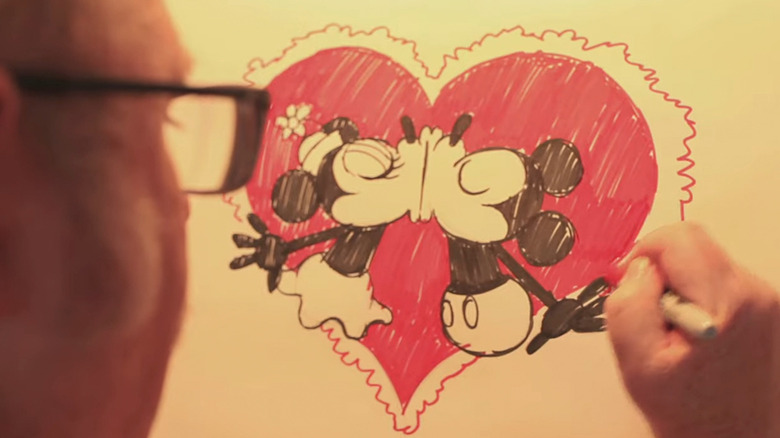

Mickey Mouse was born from desperation — at least that much is true. On that trip home from New York City, Walt was raging, vowing to be his own boss from then on, never again working on a project he didn't own the rights to. Walt used the trip to sketch ideas, and, by the time he arrived in Los Angeles, had written out the basic outline for "Plane Crazy," a short based on a mouse named Mortimer inspired by Charles Lindbergh. When Walt asked Lillian about her thoughts, she suggested he change the name, and "Mickey Mouse" was born.

Walt liked to tell this story about Mickey's creation, and it became an integral part of the character's mythos (it's even on Wikipedia, the most trustworthy of online sources). He would cite a pet mouse he had back at Laugh-O-grams in Kansas City as an inspiration. Other times, it was a mouse he found at Film Ad Co. — one that he had trapped and trained. There were stories about Walt seeing a mouse scamper by while he was sitting on a bench; Walt catching mice in a workplace trash bin and making them into pets; and, even Walt training a mouse to sit on his desk so he could draw it, startling the women in the office.

As is often the case with Hollywood icons, these stories are fictionalized accounts intended to dramatize and romanticize a more mundane history. Bob Thomas, in his biography "Walt Disney: An American Original," notes,

[These] stories had basis in fact, but the real genesis of Mickey Mouse appears to have been an inspired collaboration between Walt Disney, who supplied the zestful personality and voice for Mickey, and Ub Iwerks, who gave Mickey form and movement.

Mickey Mouse: A legend is born

In 1955, Don Eddy wrote "The Amazing Secret of Walt Disney," published in the August edition of The American Magazine (published in the book "Walt Disney: Conversations"). Unsurprisingly, we get a flattering portrait of the American icon, one that feels uh ... let's say incongruous with the biographies by Neal Gabler and Bob Thomas. Eddy writes, for example, that "Few workers who become established ever leave, voluntarily or otherwise" — something we know from Part 3 to be untrue. Yet, even in this celebratory profile, we see the Mickey Mouse origin story coming undone:

A widely credited myth has it that Mickey Mouse was inspired by a real live mouse which lived in Disney's attic studio when he was a starving young artist. The story is apocryphal. There was never such a mouse nor such an attic studio. Mickey was an invention of necessity, dreamed up out of thin air on a railroad train carrying despondent young Walt Disney and his bride to California from New York after a crushing, disillusioning defeat in his first hand-to-hand encounter with Big Business."

This is the version of events that Walt himself would later tell Tony Thomas in a 1959 interview (also in "Conversations"). He briefly outlines how he lost the rights to Oswald (without naming Mintz) and explains he used the three-day train ride with his wife to brainstorm ideas. Given that he had previously had mice as supporting characters, and in the cartoon industry at this time "they'd been used, but never featured," it seemed like a smart bet for a new breakout icon.

Walt would confirm this story again in another 1959 interview, this time with David Griffiths ("Conversations"). In this version though, he did add a possible inspiration for the apocryphal origin story:

"Yes, I had [a pet mouse] during my grade school days in Kansas City. He was a gentle little field mouse. I kept him in my pocket on a string leash. Whenever things seemed to get a bit dull between classes, I would let him rove about on his leash under the seats to get laughs from the other kids. And he got laughs — until the teacher rather sharply disagreed with my sense of extracurricular activities and made me keep the little beastie at home. Perhaps it was the fond memory of him — and of others of his clan who used to pick up lunch crumbs in our first cartoon studio, the family garage, that came to mind when we needed so desperately to find a new character to survive ... Mickey Mouse's country forefathers, you might say."

Even when setting the record straight, Walt seems unable to hold back his natural storytelling instinct.

The true story of Mickey Mouse

The true story of Mickey Mouse's creation goes something like this: after brainstorming on the train ride home, Walt went to his most trusted confidants, his brother and partner Roy, and his old friend Ub Iwerks, determined to start a new series. They still had three outstanding Oswald the Rabbit cartoons to produce before Winkler Pictures took over, and the men used that time to work on a new character in secret. The bit about "Plane Crazy" being based on Charles Lindbergh's record-breaking transatlantic flight is true, although the story concept was a collaboration between Ub and Walt, and happened much later. The first task was deciding on a new star attraction.

By 1928, Walt Disney had failed enough times to learn how the industry worked. He knew he wanted an icon to sell the pictures — a recognizable figure that he alone owned the rights to. He knew from the Alice comedies that simply copying an existing character, as the newly formed Disney Bros had done by modeling Julius the Cat after Felix the Cat, didn't work. More importantly, he knew Oswald became a hit because of his clear personality and human-like, relatable physicality. It wasn't enough for the animation to be good — the character at the center had to be likable and instantly recognizable.

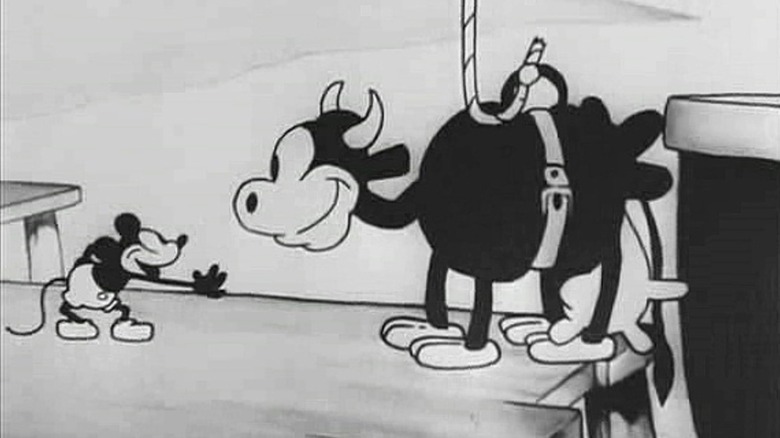

Taking what worked with Oswald, Walt, and Ub went about designing a new character. Cats had been done, and now a rabbit was on the market — so they went with a different, if equally cute, animal: a mouse. Looking back, this feels like the natural progression for Walt. Mice had featured in both the Alice comedies and the Oswald cartoons, typically as little mischief-makers looking to cause trouble. And feeling betrayed by both Universal Studios and Winkler Pictures, that's exactly what Walt Disney Studios was setting out to do.

'Mickey Mouse, built on circles and arcs'

Once the men had settled on a mouse, Walt himself drew up a model. It was too skinny — not appealing enough. Ub reworked the design, giving the mouse similar proportions to Oswald: a pear-shaped body, round features, and a distinctive elongated nose. Obviously, Oswald — who himself was modeled on the Pat Sullivan style of cartoon animals (Felix the Cat) — served as an inspiration for Mickey Mouse's general aesthetic. More importantly though, Oswald's movement was a major factor in Mickey Mouse's design; Ub wanted the character to be appealing as well as easy to animate.

The Oswald shorts often mined the comedy of the day — taking bits from Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd, and Charlie Chaplin — but part of the character's appeal was the novel melding of animation comedic convention with live-action filmmaking techniques. Walt was experimenting with camera angles and different framings. What's more, the Oswalds emphasized characters expressing broad emotion, demonstrating their feelings with exaggerated, playful gestures and posture — what we might today label as "clowning."

As Russell Merritt notes in his essay "From Alice to Mickey" (published in the collection "The Walt Disney Film Archives: The Animated Movies 1921—1968"):

Oswald himself is a forerunner to Mickey Mouse, built on circles and arcs that had an inherent graphic appeal and were easy to animate. The emphasis was on a more flexible kind of movement and a rounded design [...] But his most important quality was his soft pliability. [...] When Oswald's body is twisted, stretched, or tweaked, Oswald hurts. His mouth opens wide, his eyes roll or squint, his face squeezes. When he is tickled, he giggles. He is, like his predecessors, made up of crazy parts that will bend and detach, but the crucial distinction is that he responds to physical stimuli in humanly recognizable ways.

Plane Crazy and The Gallopin' Gaucho

Neal Gabler identifies another inspiration: the comics of Clifton Meek. In an interview with Mary Braggiotti, published by the New York Post in 1944, Walt said that he "grew up with those drawings," and commented on the cute round ears of Meek's Johnny Mouse. Looking at the mice in the old Alice comedies, or even in the Oswald the Lucky Rabbit title cards, they feature oblong ears. The iconic, circular mouse ears we all know and love originated with Mickey Mouse as his signature feature.

Walt and Ub went about producing their first Mickey Mouse short in secret, bringing a similar charming physicality to the characters and situations that had worked so well before. While the rest of the studio was finishing up the Oswald cartoons, Ub was drawing up "Plane Crazy." If someone entered his office, he'd quickly hide the drawings. The rest of the animation was done outside the studio in Walt's garage (not unlike his early forays into animation back in Kansas City). "Plane Crazy" premiered in May 1928 to warm — if not overwhelmingly positive — reviews and Disney began work on the follow-up, "The Gallopin' Gaucho."

Going full steam ahead less because of creative momentum and more out of desperation, Walt Disney Studio began work on a second Mickey short before finding a distributor for the first. "The Gallopin' Gaucho" was a parody of the 1927 film, "The Gaucho," depicting Mickey as an Argentinian swashbuckler, fighting with Pete over Minnie's affections. None of the characters are really recognizable except Pete — the animation is crude, Mickey is pretty mean-spirited, and Minnie is a little too sexy (also "The Gallopin' Gaucho" shows Mickey smoking, which feels super weird in 2023). Although promising, the shorts weren't good enough to land Walt a distribution deal. Something was missing.

What Mickey needed was sound.

Steamboat Willie strikes a chord with audiences

Walt Disney suggesting the Mickey Mouse cartoons needed sound was simultaneously forward-thinking and predictable. After the massive success of "The Jazz Singer" in 1927, Hollywood was changed seemingly overnight: that film raised the bar significantly for all the studios, which were now in a race to produce the next hit "talkie." For cartoons, however, the transition was less clear. This is because the idea of animation was still tied to drawings — a concept I explored back in Part 1 of 100 Years of Disney Magic. In its infancy, animation was thought of as "cartoons that moved"; even in Walt's own early forays in the medium, the Newman Laugh-O-grams, he approached the content from the perspective of a cartoonist drawing the action.

Essentially, as Neal Gabler writes, in his Walt Disney biography,

"... there were psychological hurdles to overcome in the very notion of talking animations. Though audiences expected to hear people talk or sing, they were not initially accustomed to hearing voices from drawings."

This "psychological hurdle" is essentially what gave Disney an edge. Walt's competitors either already had a sound cartoon produced or had such a project in the works by the time he got started on the third Mickey Mouse short — but none of these made even close to the impression as "The Jazz Singer" or "Steamboat Willie." Take "My Old Kentucky Home," a sound animation by the Fleischer Brothers that came out in 1926. It's amusing enough, but not really remarkable, and this is partially because it struggles to actually embrace using sound as part of the story. It may feature synchronized sound, but the way it is used feels like a silent film.

'We had to work it out mathematically'

Walt Disney knew that Mickey Mouse needed sound, but he also knew that it had to be done right. It wouldn't be enough to just have music playing while the cartoon action happened on-screen — it needed to be integrated. To accomplish this, they needed to know how to measure the speed of animation versus the music's tempo. Animator Wilfred Jackson brought in a metronome, which they used to figure out a tempo to match the animation. They then planned the action so that the sound effects could be spaced out to match the music.

Walt described the challenges of putting cartoons to sound in a 1929 interview with Florabel Muir, from New York Sunday News:

"It is the rhythm that has appealed to the public [...] the action flows along and we have to work hard to keep the movement flowing with the music. We had to work it out mathematically."

After figuring out how to add music to "Steamboat Willie," Walt had to convince his team that it would work. He set up a test screening. Ub Iwerks animated a rough sequence of Mickey at the steamboat's wheel, and Walt arranged for Jackson to play harmonica and other animators to make various sound effects (Walt did the voices). The boys then experimented with playing the sequence on a makeshift projection sheet and matching it with sound. Several wives served as an audience. By 2 a.m. the women were bored and wandered away (much to Walt's chagrin) — but for the men, seeing it in action like that, they felt energized. They knew they had the answer to making a cartoon talkie.

That is, they had the theoretical answer. Now was the hard part: actually getting to make the film.

Walt Disney gets in sync

The path to actually producing "Steamboat Willie" was fraught. Walt first had to figure out how they would package the film with sound. After wisely deciding against the phonograph method (which relies on the projectionist to sync up the film and the record), Walt set about finding a person who could put sound on the film. RCA had a system, but Walt was unimpressed with the audio quality. He went with Pat A. Powers, who had a licensing deal with Cinephone, a system that printed the audio onto the side of the film, which was then read by the projector. With Powers' help — and money that Walt Disney Studio really didn't have — Walt set about recording the music for "Steamboat Willie."

Being a trailblazer is expensive. Walt learned this the hard way (especially after ruining a take by accidentally coughing into a mic). Powers helped on the technical side and set up the recording session. The first attempt was, to put it lightly, a trainwreck. The 17-piece orchestra just couldn't play in sync with the animation. Walt provided a visual guide for tempo in the form of blank film with a line to indicate the beat. This proved difficult to follow, and after spending a whopping $1,000 on the day of recording, he had nothing to show for it. It didn't help that the conductor Carl Edouarde felt that "comedy music was beneath him" (per Gabler).

Not one to quit, Walt had his brother Roy Disney pursue a bank loan and went ahead with another expensive recording session. Since the conductor had difficulty staying in time with just the quick visual cue, Disney tried a film that had a bouncing ball and a soft audible "click" to indicate the beat. This worked, and after just three hours, Walt had the sound for his first sound picture.

Disney seeks distribution

All the while Disney was in New York City working with Powers on "Steamboat Willie," he was also hitting the pavement, trying desperately to secure a distribution deal for his existing Mickey Mouse shorts, "Plane Crazy" and "The Gallopin' Gaucho." Days stretched into weeks, stretched into months — and although he got plenty of positive feedback, no one was buying. Audiences were cooling on the rubber hose cartoons, and the silent Mickeys weren't really doing anything Oswald, Koko the Clown, and Felix hadn't already done.

Once he had the music done for "Steamboat Willie," Walt (and Powers) knew they had something special. This was fresh and exciting. Yet, distributors weren't so sure. The third appearance of Mickey Mouse was patently better — I'd argue even without the innovation of sound, the animation is a bit cleaner and the characters more charming — but would audiences buy it? As Neal Gabler discusses in his Walt Disney biography, the timing was awkward. After "The Jazz Singer," everyone knew change was coming. Distributors didn't want to invest in silent cartoons because they felt outdated. At the same time, no one had quite figured out how to do sound cartoons either, so it felt like a gamble.

Walt did have an in at Universal, and even enjoyed the chance to stick it to his old frenemy Charles Mintz who also was trying to get a deal with the studio; however, the offer ... sucked. The executive (a guy named Metzger) said they would order a series of Mickey Mouse cartoons if they could package "Steamboat Willie" with the film "Melody of Love," set to play at Colony Theater, and audiences liked it. Disney would not be compensated for this initial screening. There was some more back and forth, but ultimately, no deal was reached.

Eventually, Walt met a guardian angel in Harry Reichenbach, a man Gabler describes as a "self-professed ballyhoo artist and proud of it." Reichenbach managed the very Colony Theater Universal had wanted to screen "Steamboat Willie" in. Disney wanted $1,000 and, despite that being steep for the time, Reichenbach agreed. "Steamboat Willie" debuted on November 18, 1928. The reaction was both immediate and overwhelming.

In one evening, Disney revolutionized the world of cartoons.

Steamboat Willie revolutionizes the industry

In one evening, "Steamboat Willie" pushed the world of animation into the next age. As Gabler writes,

Just as "The Jazz Singer" had sent shock waves through the film industry a year earlier, rival animation studios immediately recognized that "Willie" had wrought revolution in their art. ... Other studios raced to catch up, but Disney had both a head start now and his special synchronizing system, and it would be a year before competitors were making musical cartoons of their own with anything like the fusion of "Willie."

The trades responded enthusiastically to the press screening, declaring once and for all that yes, cartoons could be talkies. In fact, they should be. This was effectively a death blow to series like Felix the Cat and Oswald the Lucky Rabbit. Although they continued to be made and shown, both series — formerly major hits, complete with merchandising — would dwindle into obscurity by the early '30s. Even Max and Dave Fleischer's Out of the Inkwell Films declared bankruptcy by the end of the '20s — although they would bounce back under Paramount in the following decade, producing both Betty Boop and Popeye.

Regardless, Disney finally proved that his ambitious, quality-driven approach to animation would pay off. He had created a character that resonated with audiences, while also establishing Disney as a studio known for its music. Douglas Brode argues in "From Walt to Woodstock: How Disney Created the Counterculture":

Dance has always been as essential to Disney films as the music itself. His first synchronized-sound cartoon, "Steamboat Willie," featured Mickey, making music with whatever he finds handy aboard ship while dancing wildly. The Mouse does not choose to dance, rather does so because he knows no other way to exist ... The vision looks forward to young people of the rock 'n' roll generation, who likewise didn't merely listen to their music, rather becoming fully at one with it.

Soon after the short's debut, offers for more Mickey Mouse cartoons came rolling in. Firmly demanding independence as a studio — Walt wanted to avoid the vulnerable position he had found himself in with Universal while making the Oswalds — Walt turned down several offers on his studio. Powers proved invaluable again, sorting out licensing deals with various states and even the foreign market. Finally, Disney's steadfast commitment to quality was paying off, and he was on the road to success.

Little did he know, that by throwing in his lot with Powers, he had signed a deal with the devil.

Join us next week for 100 Years of Disney Magic Part 5, where we'll discuss the experimental "Silly Symphonies."