The Twilight Zone's 'Disastrous' Videotape Episodes Led To Two Separate Lawsuits

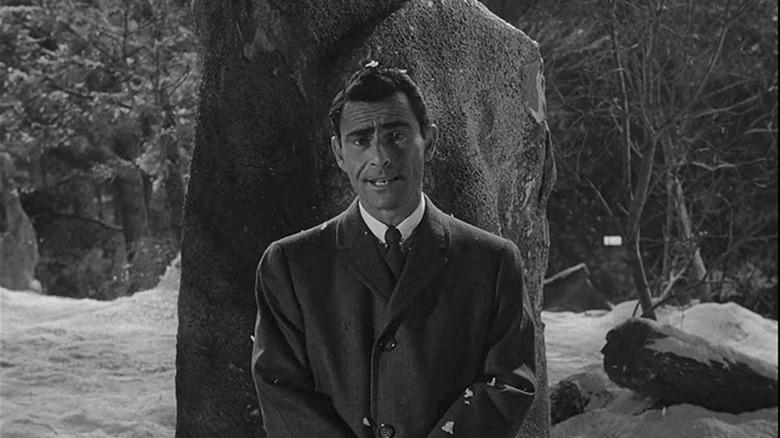

Within the lore surrounding Rod Serling's original "The Twilight Zone," which ran from 1959-1964 on CBS, the six episodes videotaped (as opposed to shot on film) during the second season are generally regarded by both fans and creators to be some of the series' biggest failures. These episodes are rivaled in reputation only by the shortened season of hour-long episodes (as opposed to the series' usual half-hour length) during the show's 4th year.

In both cases, these changes were mandated by the network, and were not internal decisions made by Serling or his crew. However, while the 4th season hour-length episodes suffered more from script and pacing issues, the videotaped second season episodes are by and large solid "Twilight Zone" scripts; it's the technical side of things that suffered instead, as CBS tried to cut the show's production costs.

The fact that these episodes were still pretty great sci-fi parables at heart unfortunately only led to more problems related to them, not less. That's because they inspired not one, but two separate lawsuits wherein unknown writers claimed to have come up with their stories first. This wasn't the first (or last) time such a thing would happen to Serling or "Twilight Zone," but it certainly added insult to injury.

Serling admits the series' mistake shooting on tape

One might reasonably wonder why Rod Serling would acquiesce to the demands of the network to change the show's format when "Twilight Zone" certainly didn't need any help, becoming one of the most influential shows ever made. For one thing, Serling knew that he was in CBS' debt in being allowed to make the show in the first place, and for another, "Twilight Zone" was not the runaway success it may be assumed it was; in fact, it found itself canceled on two separate occasions.

So, Serling was more or less at the network's mercy, even if he and others could see from the get-go that making such a change as shooting on videotape would be detrimental to the series. Although the show's production company, Cayuga, ended up saving $5,000 per episode on the videotape eps, the visual and artistic hindrances proved too much to bear. As chronicled in Marc Scott Zicree's "The Twilight Zone Companion," Serling made his feelings on the matter plain during a 1972 interview with Douglas Brode in Show Magazine:

"I never liked tape because it's neither fish nor fowl. You're bound to the same kind of natural laws as in live TV, but they try to mix it with certain qualities of film ... on 'Twilight Zone' we tried six shows on tape, and they were disastrous."

Submitted for Serling's disapproval: two separate lawsuits

While Serling and the rest of the show's personnel were disappointed by the way the videotaped episodes looked and felt, they couldn't even let bygones be bygones, as they shortly found themselves hit with two lawsuits regarding two of the six episodes. "Static," about a radio that seems to tune into the past, and "Long Distance Call," about a boy who uses his toy phone to communicate with his recently deceased grandmother, were alleged to be the intellectual property of other writers who supposedly wrote their stories before the episode's writers (Charles Beaumont for "Static," and Beaumont and William Idelson for "Long Distance Call").

While the cases ultimately resulted in settlements being made, the issue is essentially one of countless instances where parallel thinking (as opposed to outright theft) within the realm of genre is to blame. As producer Buck Houghton recalled in Zicree's book, it was a problem that plagued Serling continually:

"There were accusations floating around all the time that Rod was stealing every story that was ever written, and Rod was very self-conscious about it. [Science fiction] is a limited field, and you can't write in it without stepping on somebody's former idea. It's like saying that every love story is a steal of 'Romeo and Juliet.' You know, boy gets girl, boy loses girl, boy wins girl is not copyrightable. But there was this feeling."

Although the phenomenon of parallel thinking has only gained more credibility in the last decade or so — just look at the way jokes on social media closely resemble each other while only one of them goes viral — the feeling of propriety over an idea will continue to be an issue. Though it'll likely be more of a moral one than a legal one; after all, the writers of "Long Distance Call" didn't sue the writers of "Poltergeist II: The Other Side," which makes use of the same gimmick. As the saying goes, "good artists borrow, great artists steal."