Dimension-Shattering Behind-The-Scenes Stories From The Twilight Zone

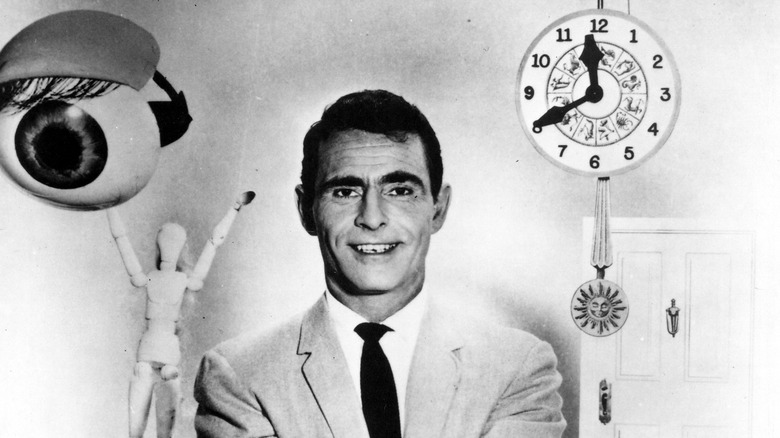

"The Twilight Zone" may have only lasted for five seasons during its initial run from 1959 to 1964, but its legacy appears to be eternal. In addition to being revived multiple times over the decades as well as receiving the feature-length treatment from Steven Spielberg and John Landis, the original show is widely regarded as one of the greatest in television history. It's no secret that "The Twilight Zone" was the brainchild of Rod Serling, who wrote most of the episodes and doubled as its suave yet mysterious narrator. In that capacity, he delivered many classic stories that took audiences to strange and wondrous places, blending elements of sci-fi, horror, and fantasy.

However, while the immense imagination behind "The Twilight Zone" alone cements its position in the pantheon of classic TV shows, what really made it so special was its intelligence. On the series' surface, it rated as a piece of well-made escapism. But dig a little deeper, and you're treated to thoughtful parables about the human condition and our capacity for both good and evil. Serling and his writers mastered the art of seamlessly weaving universal themes into tales involving aliens, other-dimensional beings, and supernatural entities. Entertainment has rarely been as enlightening as "The Twilight Zone." And so, let's look at what went on behind the scenes of this beloved series.

It was canceled – twice

Considering how beloved "The Twilight Zone" is today, it's hard to believe that it wasn't a massive success during its initial run. While well-received by fans and critics of the time, it wasn't exactly a runaway hit, which may explain why it was canceled on two different occasions. The first time came after Season 3 when, after struggling to land a sponsor, CBS pulled the plug. Also, studio executive James T. Aubrey supposedly felt little fondness for the series, which didn't help matters, and so the next work replaced it with the comedy, "Fair Exchange." Of course, "Fair Exchange" proved even less popular with the masses, prompting CBS to bring back "The Twilight Zone."

The show's renewal may seem like a blessing, but it came with a cost: the first three seasons were in a half-hour format, but its revival saw it forced into a full-hour format. Creator and main writer Rod Serling had written most of the show's episodes, and bordered on exhaustion by the end of Season 2. Pressured him into writing hour-long episodes pushed Serling to his limit and the quality began to wane. Even when "The Twilight Zone" returned to its half-hour format for Season 5, audiences had largely left and CBS canceled it again.

The show's creation was inspired by a tragic racist incident

"The Twilight Zone" never shied away from exploring themes of bigotry, intolerance, and our capacity for cruelty, so it's no wonder that one of the most heinous crimes in 20th-century America played a role in its conception. The crime in question: the murder of 14-year-old Emmett Till on August 28, 1955. His murderers -– Roy Bryant and J.W. Milam -– viciously tortured and killed the young Black boy for supposedly making inappropriate advances towards Bryant's wife Carolyn days prior. The details of the men's treatment of Till are too graphic to print here, but his family's decision to have an open-casket funeral for their son came about to draw attention to the callousness that so many African-Americans endured at the time.

This tragic incident caught the attention of Rod Serling, prompting him to write a teleplay about it. Of course, taking into account how controversial the subject was (Till's murderers were acquitted, after all), networks expressed no interest in producing a show about it. Determined to create a program that confronted the injustices of the day yet hamstrung by studio mandates, Serling created a socially relevant vehicle that he could disguise as mere entertainment: "The Twilight Zone." The show's insightful commentary was no accident, as Serling himself once said that the writer "must have a position, a point of view. He must see the arts as a vehicle of social criticism and he must focus the issues of his time."

Rod Serling used the show to comment on society's ills

Before Rod Serling created "The Twilight Zone," he served as a paratrooper in the military and experienced plenty of combat. Of course, like many people who experience the horrors of war, he returned with a deeper understanding of the atrocities that man is capable of. Serling's daughter, Anne, told Inside Edition that "he was so traumatized that when he finally did go to Antioch (College in Ohio), he switched his major from phys ed to language and literature. He said he had to get it out of his gut. He had to get it off his chest."

Serling focused his time after college examining his wartime life through teleplays, which formed the basis of the "Westinghouse Desilu Playhouse" episode, "The Time Element." The show follows a man mysteriously transported to December 6, 1941, but no one believes his warnings about the impending attack on Pearl Harbor. The episode proved successful enough to warrant a similarly-styled series, "The Twilight Zone," which saw Serling explore even more social issues with greater depth. Nick Parisi, author of "Rod Serling: His Life, Work, and Imagination," told Inside Edition, "One of the things that endears Rod Serling to people through the generations is this feeling, this sense you get that he really was on the side of the little guy. He was always standing up for the underdog... When he saw injustice he was going to speak about it."

Rod Serling was nowhere near as serious in real life as he was on the show

Rod Serling was the perfect man to introduce audiences to that "middle ground between light and shadow, between science and superstition." Mysterious yet approachable, intense yet charming, no better candidate existed to guide us in these weekly excursions into the unknown.

However, like so many of Serling's stories, there was a lot more to him than met the eye. Speaking to Inside Edition, his daughter Anne stated, "He was brilliantly funny, a practical joker, anything for a laugh... And my friends adored him. If they had any apprehension at first before meeting him, thinking he would be that black-and-white image, that quickly dissolved." This revelation may be a shock to many, but becomes less surprising when considering Serling's profound understanding of the duality of humans; it's not a stretch that someone who has a close relationship with the dark side of our existence could exude such a pleasant disposition. Serling experienced plenty of inhumanity during his time in the military, but dealing with the horrors of war probably increased his capacity to be a fun-loving goofball, such as putting a lampshade on his head at parties, as Anne lovingly recounted.

The show's first composer was the legendary Bernard Herrmann

Even if you've never seen a single episode of "The Twilight Zone," its theme grew so ingrained in popular culture that you've more than likely heard the bizarre-yet-catchy four-note motif. However, that immortal theme wasn't there from the beginning, as it initially boasted (at least in this writer's mind) an equally captivating piece of music from Alfred Hitchcock's right-hand man, Bernard Herrmann. That's right, the mind behind the scores of such classic movies as "Citizen Kane," "Vertigo," "Psycho," "Taxi Driver," and countless others, wrote the first theme for "The Twilight Zone."

However, the suits at CBS didn't particularly appreciate the theme, so it got chopped up a bit and given a new animated segment to accompany it. Still not up to their standards, the network initiated a search for a new theme. Other composers received the opportunity to concoct something, including such top names as Leith Stevens and Jerry Goldsmith. Heck, they even let Herrmann try to conjure up something better than he initially offered. This may all seem like typical studio executive indecisiveness and fussiness, but since the constant meddling gave way to something even more memorable, let's give them a pass for this. And speaking of that now-famous theme...

The composer behind its iconic theme went uncredited for years

Still not happy with the results from various major film and TV composers, CBS music director Lud Gluskin hatched a scheme: Piece together several cues written by a composer from Europe, where American film industry union rules didn't apply, so that the studio could secure high-quality music for cheap. Gluskin was well-versed in this practice. The composer whose music was patched together into a weird sonic Frankenstein? Marius Constant, from Romania. He stated, "I received a phone call from a producer, and he said, 'We're doing this TV show and I'll give you $200 to write a theme by tomorrow. If your work is accepted, you'll make another $500.'" The struggling composer couldn't pass up the deal, so he submitted some musical cues and got paid months later... without being formally told where the music would be used.

The cobbled-together theme debuted at the start of Season 2, and TV history was made. Even upon the show's cancelation, the "Twilight Zone" theme lived on in various forms, including as a jazzy disco number by the Manhattan Transfer in 1979. Still, Constant never earned a credit, at least not until the release of the soundtrack to 1983's "Twilight Zone: The Movie." A lawsuit ensued that resulted in Constant losing any money he may have been owed since his music was used, but with him gaining future rights. Better late than never, right?

One of its episodes is an Academy Award-winning short

You read that right. The Season 5 episode, "An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge" (based on the 1890 Ambrose Bierce short story), prior to its airing, won the Oscar for best live-action short film, and was also the recipient of the best short subject award at the 1962 Cannes Film Festival. So how did such a prestigious film end up as an episode of "The Twilight Zone"? By Season 5, the series's producers struggled to stretch its budget across 36 episodes, which typically cost around $65,000 per episode. The show's producer William Froug decided to buy the rights to air the French short film as an episode, which cost him only $25,000. Of course, it needed to be edited down a bit to fit the standard runtime, but hey, it beats shelling out an extra $40,000.

But why "An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge" in particular? On the surface, it doesn't have much in common with most "The Twilight Zone" episodes. This 1862-set tale of an outlaw who manages to escape his own execution to reunite with his family lacks the series' typical moralizing or ironic edge. However, its eerie tone, exploration of the darker regions of the human experience, and sense that nothing is quite what it seems allow it to sit comfortably (for the most part) among the show's best episodes.

The series' first narrator was fired for sounding too pompous

Every "Twilight Zone" fan knows how inextricably linked its creator Rod Serling was to the series; in addition to conceiving the idea in the first place and writing most of its episodes, he also narrated it, serving as a stylishly cryptic one-man Greek chorus. For most fans, Serling and "The Twilight Zone" are one and the same. However, that wasn't always the case.

You see, with Serling known only as a writer, no one contemplated him narrating the show until another candidate – Cornelius Westbrook Van Voorhis — failed to work out. Nicknamed "The Voice of Doom," Van Voorhis' striking tones informed tens of millions of Americans of the world's happenings in newsreels throughout the 1940s. He seemed very much the ideal candidate to narrate "The Twilight Zone," but his near-perfect diction — initially heard in the pilot, "Where Is Everybody?" — was deemed excessively pretentious for the show's fantastical subject matter. Orson Welles was also considered for the gig but wanted too much money. Serling eventually volunteered himself, and the rest is history. Funny side story: During an early recording of the opening narration, Serling mentions the "sixth dimension," but this was changed when he and the producer couldn't even identify the fifth dimension.

Rod Serling was the only writer who could use the word God in his scripts

Rod Serling's role as narrator of "The Twilight Zone" saw him function like a god within the show itself, always watching and commenting on the weird happenings but never interfering and always invisible to this world's inhabitants.

He also appeared to wield god-like powers behind the scenes. Case in point: an odd rule decreed that only Serling could use the word "God" in his scripts. It may be hard to believe but no less a figure than series writer and famed sci-fi author Richard Matheson confirmed this in an Archive of American Television interview, where he stated, "I used to get ticked off at Rod because he could put 'God' in all his scripts. If I did it, they'd cross it out." While Matheson didn't fully know why, exactly, someone implemented this rule, he suspected that it may have been due to Serling's sterling reputation.

Rod Serling wrote 3 different pilots for the series

The teleplay for "The Time Element" marked Rod Serling's first real foray into sci-fi. He sent the script to CBS as part of a pitch for "The Twilight Zone." They purchased it but weren't too keen on doing something so fantastical, so they shelved "The Time Element." However, it soon got produced, as Bert Granet, producer of "Westinghouse Desilu Playhouse," purchased the teleplay and turned it into an episode of the series. "The Time Element" clicked with audiences, which prompted CBS to revive Serling's series and they engaged him to write a pilot.

The result was the script for "The Happy Place," which took place in a far-flung future where anyone 60 years and older is sentenced to death. While the show's producer William Self loved the script, he found it far too bleak as an introduction to the show and rejected it. For poor Serling, it meant heading back to the typewriter. However, the third time proved to be the charm, apparently, as the teleplay that Serling returned with –- "Where is Everybody?" -– was precisely what the doctor ordered and was produced as "The Twilight Zone" pilot. The episode actually lacks the more bizarre and otherworldly elements that would become "Twilight Zone" trademarks, but its perfect blend of intriguing plot and suspenseful mystery adequately established the series' tone.

George Takei starred in an episode that CBS pulled after one airing

Before boldly going where no man has gone before on the original "Star Trek" series, George Takei made a name for himself tackling bit parts on various TV series and feature films, including "Perry Mason" and "Hell to Eternity." However, in one of his more interesting yet forgotten early roles, he played a prominent character in the "Twilight Zone" episode, "The Encounter." It casts Takei as a Japanese gardener who strikes up a conversation with a WWII veteran, only for their chat to slowly reveal their true pasts. While among the show's very best episodes, "The Encounter" delivers some nice surprises alongside a profound statement about how war takes more than just lives.

It's worth noting that CBS pulled the well-intentioned episode following numerous complaints from many Japanese-Americans for its insensitive depiction of them and their culture. Due to the controversy it generated, "The Encounter" went unaired for decades. In an interview, Takei stated that the episode "has the unique distinction of being the only 'Twilight Zone' (episode) that aired only once. It's never been re-aired. It's never enjoyed a re-run. And shucks-darn, I missed out on my residuals on that one!" The episode eventually aired on January 3, 2016, during Syfy's New Year's Day "Twilight Zone" marathon; while its portrayal of Japanese-Americans comes off even worse today than it did more than 50 years ago, hopefully, Takei can start making some money from it.

Rod Serling isn't entirely sure how he came up with the show's name

Like so many "Twilight Zone" plots, the origin of the show's name itself is unsurprisingly enigmatic. In fact, it's such an enigma that even series creator Rod Serling couldn't fully recall he conceived of it. According to American Scientist, Serling said, "I thought I'd made it up, but I've heard since that there is an Air Force term relating to a moment when a plane is coming down on approach and it cannot see the horizon. It's called the 'twilight zone,' but it's an obscure term which I had not heard before." He served in the military before entering the television business, so this explanation does make sense. How it came to him when he was creating one of the most iconic television programs of all time, however, remains between Serling and his muse.

American Scientist outlines several other uses of the term "twilight zone" that predate the show, giving it an oddly fitting elusive quality. One instance in particular sounds very much like something that Serling himself would narrate in a "Twilight Zone" episode. The 1946 essay, "Science and Art: An Approach to a New Synthesis," include the following statement: "A philosopher with a deep insight into mathematics and the process of scientific and philosophic thinking, John Dewey, in his 'Art and Experience,' has beautifully clarified and illuminated that twilight zone of creativeness where both artists and scientists function."

Nightmare at 20,000 Feet was a nightmare for director Richard Donner

One of the most iconic "Twilight Zone" episodes ever produced, "Nightmare at 20,000 Feet," follows a man who, while on a flight, sees a strange creature wreaking havoc on the wing of the plane. He tries to warn the other passengers, but no one believes him, causing him to question his sanity. Besides the goofy-looking creature, it's wonderfully suspenseful and delivers a terrific reveal at the end. But "Nightmare at 20,000 Feet" gained recognition for more than just its stellar premise; it featured top talent both in front of and behind the camera. Legendary sci-fi author Richard Matheson wrote the episode, which starred a pre-"Star Trek" William Shatner in the lead role. The director? Richard Donner, who later helmed such films as "The Omen," "Superman: The Movie," "The Goonies," and the "Lethal Weapon" series.

Unfortunately, Donner endured a hell of a time shooting the episode, despite having directed TV shows for several years at that point. This episode required multiple special effects, which were incredibly difficult to oversee. According to the director, "A man flying in on wires. Wind. Rain. Lightning. Smoke, to give the effect of clouds and travel and speed. Actors. You couldn't hear yourself think because of the noise of the machines outside. And fighting time, all the time. It was just unbearable. If any one of those things went wrong, it ruined the whole take."