There's A Reason Why Six Twilight Zone Episodes Will Always Look Terrible

It doesn't matter how popular a TV series is: If it costs money, the network is going to try to save money. Sometimes that means turning the second season finale of "Star Trek: The Next Generation" into a god awful clip show. Sometimes that means making the whole fourth season of the helicopter action/adventure series "Airwolf" without the original cast... or the helicopter.

In the case of the classic series "The Twilight Zone" — a critically acclaimed, Emmy-winning sci-fi/fantasy/horror anthology created by one of the most celebrated writers working in television, Rod Serling — there was no continuity, and therefore no clip show. There was no regular cast, so no regular cast to cut.

As a result, when the second season of "The Twilight Zone" turned out to be very, very expensive, the producers made a decision that barely saved any money, artistically hindered the program, and left us with six episodes that currently and, sadly, will always look bad compared to the others.

That's because they were shot on videotape.

The tape of things to come

According to producer Buck Houghton in "The Twilight Zone Companion," in the second season of the show they were "inching up to around $65,000 an episode, which at that time was frightening."

So the decision was made to shoot six episodes, in a row, on a soundstage using video cameras. The set-up would be not unlike many sitcoms, with the episode's editing performed on the fly, by switching between multiple cameras that filmed the action simultaneously. Theoretically the measure could save money, but it came with creative drawbacks. External locations were not possible, not without using stock footage or recreating outdoor environments on a soundstage, an effect which was not very convincing. Video cameras also limited the options for cinematic camera movements, giving the episodes a stagey, often stodgy feel akin to contemporary soap operas.

These episodes wound up transferred to 16mm film stock, but watching them today, the damage is still done. Some episodes feature distracting dark grey halo effects surrounding the actors, which is especially noticeable when they move. Minor digital imperfections sometimes pop up, like watching an old home movie on VHS that's been played one too many times.

And again, that's just the way these episodes look, so "fixing" them isn't really a consideration. They were made a little broken in the first place.

A couple of these six "Twilight Zone" episodes — which were all aired out of order, and sandwiched between episodes shot on film — were written and performed so beautifully that, despite their technical limitations, they remain some of the series' best installments.

The other ones ... were not, and some of them are rarely even discussed anymore.

Video kills, the radio's bizarre

The first "Twilight Zone" episode recorded on tape was designed to make the most of the medium's limitations: a single-location sci-fi mystery called "The Lateness of the Hour." The episode stars Inger Stevens — who had already headlined in one of the show's most celebrated episodes, "The Hitch-Hiker" — as Jana, a young woman living with her parents in a house full of robots, who wait on them hand and foot. Jana tries to convince her parents to dismantle the staff so they can live like human beings again, but as you can imagine, since this is "The Twilight Zone," she's in for a surprise.

The stilted staging and drab video imagery doesn't help "The Lateness of the Hour," but then again, the screenplay is somewhat inert. There isn't nearly enough action to hide or even distract the audience from the show's rather obvious twists.

The second episode filmed in the format, "Static," stars Oscar-winner Dean Jagger ("Twelve O'Clock High") as a man who hates modern television and digs up an old radio which, magically, plays old live programs that weren't recorded, and can't possibly be re-runs. Overcome by nostalgia, it appears to the people he lives with that he's losing his mind, but he might just be getting a second lease on life.

"Static" is a sentimental episode of television, and its message about the way audiences relive their past through multimedia has aged well (as you can imagine). But it's a bit tonally confusing. Although the story seems convinced that it's "happy" ending is genuinely happy, it may also be an eternal descent into delusion, leaving the audience a little uneasy, and it doesn't seem like it's intentional.

Carney's big holiday

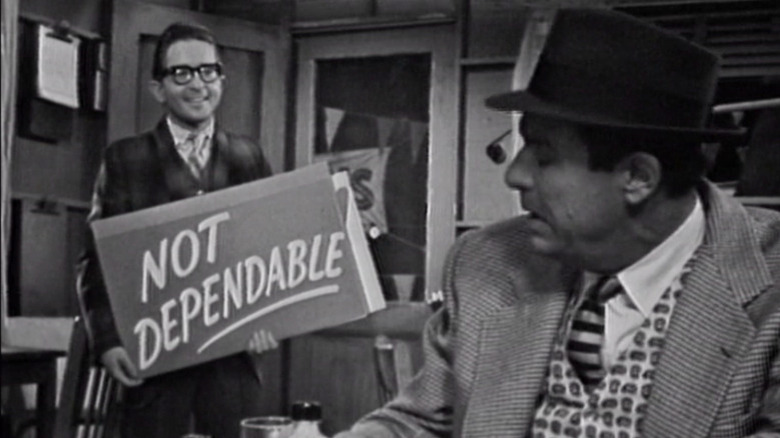

The third videotape episode, "The Whole Truth," is a comedy episode starring Jack Carson ("Mildred Pierce") as a duplicitous used car salesman who accidentally buys a cursed car, which forces him to tell only the truth. That threatens to destroy both his business and his marriage, each of which were built on constant lies. The episode ends with the con artist selling the broken-down car to Nikita Kruschev, and calling "Jack Kennedy" to tell him the good news.

The timing of the episode couldn't have been better — "The Whole Truth" aired on January 20, 1961, the same day President John F. Kennedy was inaugurated — and the premise, popularized decades later in the hit comedy "Liar Liar," yields some good belly laughs. But at no point does the used car lot actually look like it's a used car lot and not a sound stage, and that's incredibly distracting.

"The Whole Truth" was followed by one of the best "Twilight Zone" episodes ever filmed: "The Night of the Meek," in which "The Honeymooners" co-star Art Carney (also a future Oscar-winner for "Harry and Tonto") plays an alcoholic department store Santa Claus, who just wishes he could give the poor children in his neighborhood real gifts for Christmas. He stumbles across a magic sack which somehow gives everyone exactly the gift they want, which gets him into trouble with the law, but also provides the episode with a wonderful little twist.

Despite the limitations of the videography, "The Night of the Meek" is — in no uncertain terms — one of the best Christmas episodes of television ever filmed; quite possibly the very best. It's a classic holiday tale, emotional and sweet and just a little bitter, and there's a reason people revisit it every year.

Mumy dearest

The last two "Twilight Zone" episodes recorded on videotape are grim little ghost stories. "Twenty Two," based on a tale so ingrained in the popular consciousness that it's still told around campfires, tells the story of an erotic dancer named Liz (Barbara Nichols, "Pal Joey") who dreams every night that she's entering the hospital morgue, where an attendant tells her "Room for one more!"

Nobody believes her, and her doctor (Jonathan Harris of "Lost in Space" fame) is condescending and makes inappropriate remarks about seeing her shows and expecting her to wink at him. The famous ending of the tale is writ large in "Twenty Two," with a plane explosion that's pretty convincing given the technical limitations of the production, but it's a straightforward and obvious story. Still, the film's depiction of women being mistreated by men in power remains sadly potent.

The final videotape episode is by far the creepiest: "Long Distance Call" stars Billy Mumy (also from "Lost in Space") as a child whose grandmother dies, but keeps calling him on a toy telephone. She's not calling to say hello, she's calling to convince him to join her in the afterlife, which leads him to try to kill himself multiple times, while his parents react in horror, unaware that there's a supernatural cause.

Unexpectedly intense in its depiction of child endangerment, and unusually malevolent in its portrayal of the afterlife, "Long Distance Call" is one of the darker episodes of "The Twilight Zone," and even though the photography could be crisper, it remains incredibly effective.

Video killed the video star

You may recall from the beginning of the article that only six episodes of "The Twilight Zone" were shot on tape, and that was right in the middle of the show's second season. The initial run of "The Twilight Zone" lasted five seasons, and they went back to shooting on film right afterwards, so why did they go back to celluloid if the network really thought that video would save them a lot of money?

Well, it turns out that shooting on video only saved "The Twilight Zone" $5,000 per episode, a paltry amount that didn't justify torpedoing the acclaimed and popular show's entire aesthetic. And that was just fine by series creator Rod Serling, who in an interview in 1972 (via "The Twilight Zone Companion") called the episodes "disastrous."

"I never liked tape because it's neither fish nor fowl," Serling explained. "You're bound to the same kind of natural laws as in live TV, but they try to mix it with certain qualities of film."

Watching the episodes now, he's got a point. A three-camera videotape set-up works well when you're recording TV episodes that are staged like a theatrical experience, with long scenes on large sets. "The Twilight Zone" wasn't a stage show and the majority of its episodes demanded more, visually, than contemporary video set-ups could provide.

And while it's a shame that the failed cost-cutting measure undermined a potentially great episode like "The Whole Truth," and made mixed-bag episodes all the more mixed, it's a testament to the power of "The Twilight Zone" that a couple of their best episodes actually emerged from this, one of their most disastrous eras.