Were Oppenheimer's Chances Of Igniting The Atmosphere Real?

"Oppenheimer" is built around the Trinity Test, the famous 1945 event where J. Robert Oppenheimer and his team of scientists tested an atomic bomb for the first time. This historic moment is the fulcrum on which Christopher Nolan's brilliant, horrifying film turns. Everything prior to the test focuses on Oppenheimer's passion for physics and beating the Nazi's to the punch, while everything after shows how the titular physicist became haunted by his own work and was ostracized by many of his former colleagues and allies as he spoke out against nuclear proliferation.

Nolan told Entertainment Tonight that his film "has a lot to do with the consequences of actions — sort of going ahead and doing these things and then having to deal with the consequences for years afterwards." It's an understatement to say that the consequences of Oppenheimer's work were monumental. The result of the Manhattan Project, which he led, was a world forever changed. But you can at least say these consequences were perhaps preferable to the potential outcome of a world incinerated. As Nolan told ET:

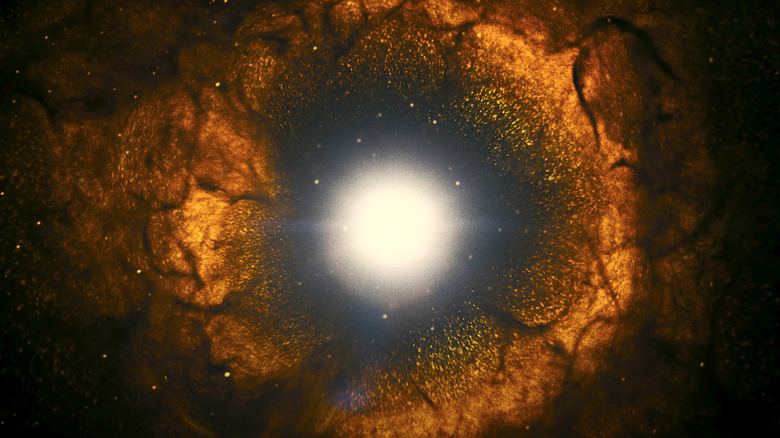

"Oppenheimer was running the Manhattan Project and they were doing their calculations, early on they saw the possibility that when they triggered the first atomic device, to test it, they might start a chain reaction that set fire to the atmosphere and destroyed the whole world."

This seems to be one of, if not the main element of Oppenheimer's story that drew Nolan towards making his three-hour biopic. As the director put it, pushing the detonator with the knowledge that this single act could wipe out humankind was, "as dramatic a scene I could imagine in motion pictures." But was this really the case? Did Oppenheimer and his Manhattan Project associates really press the button without being certain of the consequences?

The crux of Nolan's biopic

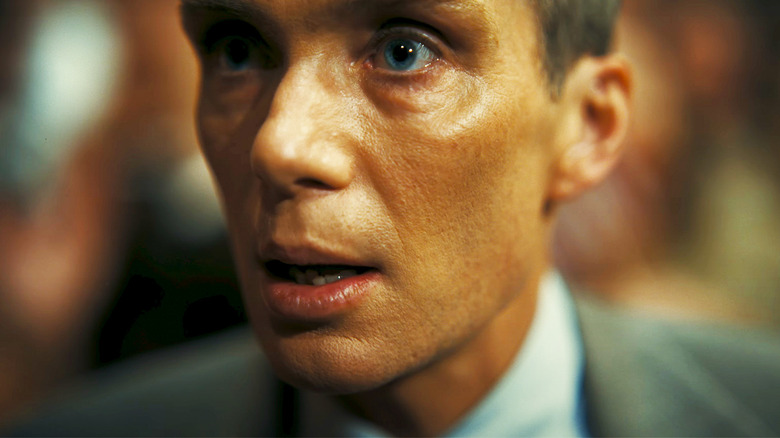

For his version of the Trinity Test, Christopher Nolan wanted to create as realistic an explosion as possible and set himself the goal of recreating a nuclear detonation without the use of CGI. In "Oppenheimer," this moment is preceded by a brief conversation between Cillian Murphy's Oppie and Matt Damon's Leslie "Dick" Groves, the US Army Lieutenant General who oversaw the Manhattan Project. In the darkly humorous back and forth, Groves asks, "Are we saying there's a chance that when we push that button, we destroy the world?" to which Oppenheimer responds, "Chances are near zero."

This is Nolan's big moment. The "dramatic" scene that captured his attention early on. The director certainly manages to build the tension as the score escalates and the countdown to the test begins. But in reality, when Oppenheimer and co. actually hit the detonate button, were the chances of destroying the world really "near zero"? Well, it seems there's some confusion over that question.

In a 2015 Scientific American piece, John Horgan recalls interviewing the head of the Manhattan Project's theoretical division, Hans Bethe (played by Gustaf Skarsgård in "Oppenheimer"), who seemed to categorically rule out the idea that he and his team were uncertain of the consequences of detonating the bomb. As Bethe recalls it, it was Hungarian physicist Edward Teller (Benny Safdie in Nolan's film) who first raised concerns over the atom bomb potentially setting fire to the atmosphere and causing a chain reaction that could wipe out life on Earth. Back in 1942, Bethe claimed to have sat down and "looked at the problem" before concluding that it was "incredibly unlikely." But the team needed to run further calculations to make sure. After all, this was the fate of humanity they were toying with.

'The earth would be vaporized'

In the Scientific American piece, Hans Bethe specifically recalled Edward Teller raising concerns about "nitrogen in the air" and "a nuclear reaction in which two nitrogen nuclei collide and become oxygen plus carbon," thereby "setting free a lot of energy." According to Bethe, that question "caused great excitement." But even after the German theoretical physicist was able to deem that outcome "incredibly unlikely," Teller was intent on running his own calculations. As Bethe put it:

"Teller at Los Alamos put a very good calculator on this problem, [Emil] Konopinski, who was an expert on weak interactors, and Konopinski together with [inaudible] showed that it was incredibly impossible to set the hydrogen, to set the atmosphere on fire. They wrote one or two very good papers on it, and that put the question really at rest."

Still, as you might expect, concern over the issue persisted, and is certainly present in the brilliant yet horrifying biopic that is "Oppenheimer." Nobel Prize-winning physicist and Oppenheimer's superior, Arthur Compton (who isn't portrayed in "Oppenheimer") continued to fret about setting the world on fire even after the Trinity Test. As Inside Science notes, Compton spoke to The American Weekly for a 1959 feature titled "The bomb – the end of the world?" where he publicly worried about hydrogen in the oceans and nitrogen in the air being set alight by future nuclear explosions. All of which led author of the piece Pearl S. Buck to surmise, "The earth would be vaporized," to which Compton responded, "Exactly."

Was Compton just uninformed?

Arthur Compton's comments in '59 suggest the head of the Metallurgical Laboratory in Los Alamos might not have been as convinced as his colleagues that the Trinity Test wouldn't wipe out the human race. But as Bethe reportedly clarified in his conversation with Scientific American's John Horgan:

"[Compton] didn't see my calculations. He even less saw Konopinski's much better calculations, so it was still spooking in his mind when he gave an interview at some point, and so it got into the open literature, and people are still excited about it."

Bethe also surmised that "it was absolutely clear before the Los Alamos test that nothing like [igniting the earth's atmosphere] would happen." That view was, as Inside Science points out, supported by a 1946 report authored by three scientists who'd worked on the Manhattan Project, in which they wrote:

"It is shown that, whatever the temperature to which a section of the atmosphere may be heated, no self-propagating chain of nuclear reactions is likely to be started. The energy losses to radiation always overcompensate the gains due to the reactions. It is impossible to reach such temperature unless fission bombs or thermonuclear bombs are used which greatly exceed the bombs now under consideration."

But even in the case of these larger bombs, which would of course be invented in the years following Oppenheimer's work at Los Alamos, the scientists concluded that "energy transfer from electrons to light quanta by Compton scattering will provide a further safety factor and will make a chain reaction in air impossible." The word "impossible" is quite reassuring, even if the rest of the language is a reminder of why Cillian Murphy didn't even try to understand physics for his role in "Oppenheimer."

Drama vs reality

Chain reactions are a central metaphor in "Oppenheimer," beginning with Cillian Murphy's physicist watching ripples emanate from rain droplets falling in an Oxford puddle during the movie's opening moments. That carries right the way through to the harrowing final moments of "Oppenheimer," where it's suggested that even though the atom bomb didn't wipe out humankind, J. Robert Oppenheimer started a chain reaction of scientific research and geopolitical bellicosity that will ultimately lead to our destruction anyway.

Which, when combined with Christopher Nolan playing up the drama of the Manhattan Project scientists not knowing what would happen when they tested the bomb, is why it's kind of anticlimactic to learn that there was actually no real risk of this chain reaction setting fire to the atmosphere in the first place. Obviously, there's no way to know whether Nolan was fully aware of that reality when he wrote "Oppenheimer." And there's no doubt the stakes for the Trinity Test buildup are significantly raised by Cillian Murphy's line about the chances of the world exploding being just "near zero."

In a Fandango discussion, Nolan spoke about "the moment where Oppenheimer and his team couldn't entirely rule out the idea that when they let off that first device they'd start a chain reaction that would destroy the world." The director once again focused on the cinematic potential of such a scene, saying, "That just seemed like the most incredible moment in time to take the audience to be in that room with them." Does it matter that the actual moment in time wasn't quite so dramatic? Maybe, but it hardly undermines Nolan's devastating suggestion at the film's end that no matter what happened at the Trinity Test, the chain reaction that leads to our doom has been set in motion.