The Melancholy Final Days Of Oppenheimer (Or, What Happened After The Credits Rolled)

Christopher Nolan's "Oppenheimer" begins with two on-screen titles showing the definitions between fission and fusion. For the layman or average moviegoer, the definitions serve as an explanation about the differences between two ways of achieving nuclear power. They also layout the ways in which the entire film is going to be structured, split in two by color and black-and-white sequences that divide Nolan's epic biography into Oppenheimer's subjective point-of-view and the objective forces swirling around him. The sequences in color paint Oppenheimer as somewhat of a heroic figure that helped this nation win World War II with the creation of the atomic bomb; the black-and-white sections show the famed scientist as a victim of government bureaucracy bullied by a system that no longer needs him.

Serving as the basis for "Oppenheimer," the book "American Prometheus" by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin also begins with a quote. Taken from the Greek historian Apollodorus' "The Library," it reads:

"Prometheus stole fire and gave it to men. But when Zeus learned of it, he ordered Hephaestus to nail his body to Mount Caucasus. On it Prometheus was nailed and kept bound for many years."

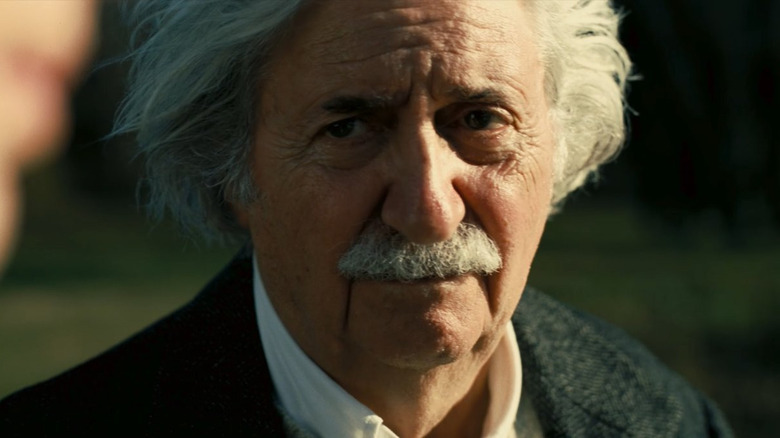

Comparing Oppenheimer to Prometheus is absolutely appropriate. As legend has it, Prometheus stole fire from the Gods and gave it to man, only to be punished severely for it. Nolan's film shows how Oppenheimer was eventually vilified and punished as well, but at nearly three hours in length, "Oppenheimer" stops short of telling the full story of the defamed physicist's life. Instead, the ending focuses on a conversation between Albert Einstein and Oppenheimer that proved to be incredibly prophetic. In truth, the last days of Oppenheimer's life were quite pained, giving credence to Einstein's predictions that history would chew him up and spit him out.

Far from a Hollywood ending

If Christopher Nolan and company ever planned to turn their film about the construction of the A-bomb into a cookie-cutter summer blockbuster, the credits would roll right after the first nuclear explosion in Los Alamos, New Mexico, on July 16, 1945. In what feels like a dip in the film's pulse-pounding momentum up until that point, the rest of "Oppenheimer" deals with the fallout (both nuclear and political) of the results on that historic day and the looming horrors of the gruesome bombings in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan.

Haunted by his own accomplishments, Oppenheimer began speaking out against the continued use of nuclear weapons, believing that the race to create the bomb had already been won by the Americans. The Nazis lost, Japan had surrendered and the A-bomb was supposed to be the ultimate deterrent that would end all war. Sadly, the jingoistic U.S. military and President Truman thought differently. As mentioned at about the halfway point in "Oppenheimer," the atomic bomb didn't just end WWII, it started the Cold War between Russia and the United States.

During the height of anticommunist sentiment fueled by the deep-seated paranoia of McCarthyism, Oppenheimer eventually had his top-level security clearance stripped from him after an exhaustive 4-week interrogation in the spring of 1954. And just like that, Oppenheimer's reputation was irreparably tarnished even though the general opinion of the scientific community at large was completely shocked by the outcome.

From that point on, Oppenheimer continued to serve as Director of Princeton's Institute for Advanced Study until 1966, where he inspired discussion surrounding quantum and relativistic physics in the School of Natural Sciences, according to Atomic Archive.

In an attempt to right the wrongs of the past, President Lyndon B. Johnson honored Oppenheimer with the Atomic Energy Commission's prestigious Enrico Fermi Award. That accolade didn't do much to restore his reputation and only made Einstein's words during the final moments of "Oppenheimer" all the more resonant.

Fission vs. fusion = Teller vs. Oppenheimer

Just two days before Thanksgiving on November 22, 1955, Russia detonated Tsar Bomba, marking the Soviets' first megaton-range hydrogen bomb. It was the result of years of work to combat against the "American threat" that all started with the Manhattan Project. In "Oppenheimer," it's eventually brought to light that German physicist Klaus Fuchs was supplying the Soviet Union information while working on the American hydrogen bomb project.

The decision to proceed with the atom bomb instead of the hydrogen bomb sparked an ego-fueled feud between Oppenheimer and the Hungarian-American theoretical physicist Edward Teller. Over a decade after the two worked together closely at Los Alamos, it was Teller who may have put the nail in Oppenheimer's coffin during his unofficial arraignment at the security hearing in 1954. Speaking at the hearing, Teller stated:

"I thoroughly disagreed with [Oppenheimer] in numerous issues and his actions frankly appeared to me confused and complicated. To this extent I feel that I would like to see the vital interests of this country in hands which I understand better, and therefore trust more."

While it's ultimately unknown how much sway Teller's testimony had, Oppenheimer left the United States for the Virgin Islands shortly after. Teller, on the other hand, remained a vital part of the scientific community, although his overall reputation never quite recovered. He had gone against a fellow colleague and revered scientist, and that kind of slight wasn't quickly brushed aside.

In addition to his historic rivalry with Oppenheimer, Teller would also go on to accuse Jane Fonda and Ralph Nader of needless "propaganda" after they both protested the use of nuclear energy after the partial meltdown at Three Mile Island in 1979. After suffering a heart attack at age 71, Teller was featured in a bizarre ad from energy company Dresser Industries in the New York Times. Blaming the strain caused from Fonda and Nader's anti-proliferation stance, Teller is quoted as saying, "I was the only victim of Three‐Mile Island."

Einstein was right

"Oppenheimer" is bookended by a fleeting, momentary conversation between Einstein and Oppenheimer told from two different perspectives. Oppenheimer's longtime associate and secret antagonist, Lewis Strauss (Robert Downey Jr.), sees both intellectual giants talking and he is immediately filled with paranoia that they are speaking ill about him. In the closing moments, the audience is allowed to eavesdrop on their exchange thanks to Oppenheimer's POV — and in true Nolan fashion, the final impact is effective and profoundly melancholy. Being much older than Oppenheimer, Einstein tells the father of the atomic bomb that history will not be kind, and his accomplishments will be reduced to meaningless political fodder and staged accolades that will always ring hollow. For the rest of his life, one moment in time will simultaneously define him and haunt him.

Oppenheimer changes the subject back to when he first showed Teller's equation, warning that they could ignite the atmosphere upon detonation. "When I came to you with those calculations," Oppenheimer says, "we thought we might start a chain reaction that might destroy the entire world." "What of it?" asks Einstein. After all he's been through, Oppenheimer responds, "I believe we did."

It's a stark, sober realization that comes over Oppenheimer's face in that final moment as he comes to the conclusion that all of his efforts to warn us about the dangers of nuclear energy have fallen on deaf ears. The powers that be only want to make a bigger bomb to defend against the possibility of an even bigger one that might be built down the line. Instead of stopping war, they have essentially guaranteed that the tools of war have only grown exponentially more deadly. One A-bomb was supposed to be the deterrent, not having two superpowers point thousands of nuclear warheads at potential targets across the globe.

An early retirement in paradise

After Oppenheimer was stripped of his security clearance in 1954, Bird describes the greying physicist in "American Prometheus" as "humiliated, terribly wounded and physically and psychologically exhausted." Disgraced, he left Princeton, New Jersey with his wife Kitty (played by Emily Blunt) and two children and sailed to St. John in the U.S. Virgin Islands. It was a stark departure from Oppenheimer's high society upbringing in Manhattan's Upper West Side, and he relished "getting back to the physicality of the natural world," Bird wrote.

According to "American Prometheus" and the BBC, Oppenheimer was also able to finally shed himself of the FBI surveillance that had been invading his life for over a decade. The Bureau simply wasn't able to spy on Oppenheimer and his family whenever they were in St. John. Free from ridicule, Robert and Kitty spent their time sailing and writing poetry. For New Year's Eve, they would throw champagne parties, hire a calypso band, and Robert would happily point out constellations to his guests.

For a man who became a giant of history and was then punished for his concerns about the future of nuclear weapons, he seems to have found some peace later in life. A constant chain smoker for years, Oppenheimer was diagnosed with throat cancer in 1965, and succumbed to the disease on February 15, 1967 after falling into a coma three days prior. He was 62.

In one last haunting glimpse into the mind of Oppenheimer, the BBC spoke with a local historian in St. John named David W. Knight who repeated a story passed down to him about why the Oppenheimers had chosen such a remote location to live. "My parents often repeated the story that the reason why Oppenheimer had chosen the U.S. Virgin Islands is that he was convinced that due to the trade winds, it would be one of the last places affected by nuclear fallout."