Oppenheimer Is The Most Christopher Nolan Movie Christopher Nolan Has Ever Made

Potential "Oppenheimer" spoilers follow.

In most auteur filmmakers' bodies of work, there exists a movie that functions as the summation of their particular themes and interests, a film that essentially "unlocks" all of their other movies, throwing them into a new light. Sometimes these movies arrive late in a director's career, acting as more of a true culmination, such as Steven Spielberg's revelatory "The Fabelmans" from just last year. Other times, these films act as statements of intent right out of the gate, as I'd argue Steven Soderbergh's first feature "Sex, Lies, and Videotape" does.

It's not unusual, however, for such a movie to arrive somewhere near the middle or back half of a director's career; after all, Martin Scorsese didn't make "The Last Temptation of Christ" until he was 46 years old and 11 films deep. In other words, these kinds of films arrive when such an artist feels both comfortable and ready to reveal themselves in a big way.

"Oppenheimer" seems to be exactly that film for Christopher Nolan. Of course, such a claim could be disproved by whatever his very next feature turns out to be, but for now, the film appears to put together as many elements of Nolan's prior work as possible while also blending it with aspects of his personal life. In this way, "Oppenheimer" — the 52-year-old's 12th film — is the most "Christopher Nolan movie" that Nolan has made.

Science fiction becoming science fact

It's tempting to call Nolan a science-fiction filmmaker, especially as a large number of his movies concern such out-there concepts as people making clones of themselves ("The Prestige"), carrying out heists in other people's dreams ("Inception"), traveling to distant worlds ("Interstellar"), and stopping an invasion of "inverted" material from the future ("Tenet").

Yet while Nolan is undoubtedly intrigued and inspired by the dramatic implications of these fantastical concepts, he's equally driven by their grounding in real-world science and physics. This interest likely stems from his childhood: he obsessively watched Stanley Kubrick's "2001: A Space Odyssey" while attempting to make his own home movies, helped along the way by his uncle, a NASA employee who built guidance systems for the Apollo missions.

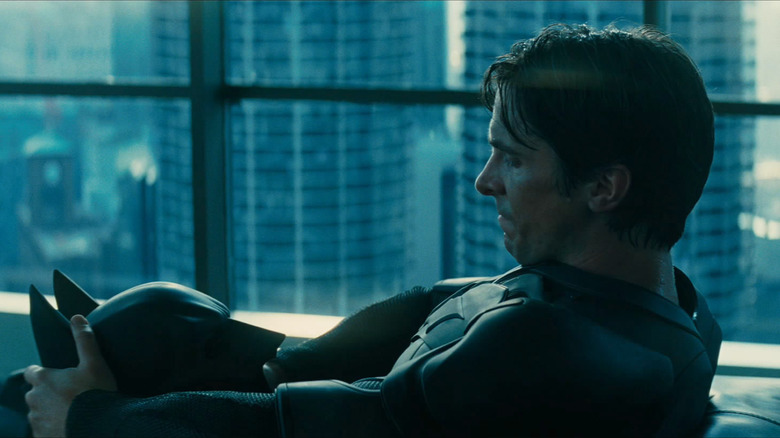

A large part of the character of J. Robert Oppenheimer (played by Cillian Murphy) in "Oppenheimer" concerns his obsession with seeing a hidden world beyond the naked eye, one filled with fusion and fission waiting to be harnessed. In other words, a world of possibility that would have seemed like science fiction before Oppenheimer and his fellow scientists made it possible. It's that ethos that fuels Nolan's sci-fi, apparent in everything from those aforementioned films to even the "Dark Knight" trilogy, where a comic-book superhero like Batman is given tech and abilities grounded in science fact.

Nolan has even gone so far as to form a working partnership with an actual theoretical physicist, Kip Thorne, who himself was friends with the likes of Stephen Hawking and Carl Sagan. Thorne has consulted on almost every Nolan film since "Interstellar," and "Oppenheimer" is no exception.

Christopher Nolan teaches you how to watch his movie

Ever since his first feature, Nolan has been obsessively pursuing new ways of experimenting with the storytelling possibilities of cinema. While some of these experiments have been resoundingly successful — we would not be living in a world where narrative films regularly premiere in the IMAX format without Nolan — others have been off-putting to some folks, resulting in even fellow filmmakers complaining to Nolan about his controversial sound mixes, for instance.

While every single Nolan movie is challenging enough to not qualify as something to watch passively (the man is too much in love with classic cinema to allow for the Netflix-ification of his movies), he's also not some smarmy snob looking to make an audience have a bad time. Each of Nolan's films essentially comes with an instruction manual tucked within the body of the movie itself, with the director dutifully laying out the rules of not just the story and its stakes but how the movie itself is to be viewed.

These orientation tutorials are different with each film. Sometimes they're literally exposition, as in "Inception," where orientation arrives in the form of a literal training montage, and in "Tenet," where the infodump is hand-waved away with a beautifully empowering line of dialogue: "Don't try to understand it. Feel it." Other times, these tutorials are structural instead: in "Dunkirk," Nolan provides a trio of on-screen titles indicating that the three plot threads in the film are unfolding over different periods of time, and in "Memento," the presence of black and white photography is a visual cue that those scenes are unfolding differently than the scenes in color.

It's these latter two devices Nolan intentionally revisits in "Oppenheimer," as the film's two interconnected perspectives are denoted by both on-screen titles at the beginning and the contrast of color and black and white film.

The fulcrum of history

In "Tenet," Nolan used the fictional time-shifting tech of that movie to introduce the concept of what he calls a "temporal pincer movement," wherein forces from the past and the future converge on a single moment in time. For "Tenet," that time was the present, a period turned into a continual secret battlefield over the future of the planet thanks to an unnamed scientist in the future discovering a doomsday device connected to inversion tech and becoming, as one character succinctly puts it, "her generation's Oppenheimer."

For Nolan, the turning point in all of human history seems to be the events just before, during and subsequent to World War II. It appears to be no accident that the only two films of his career so far based on actual events are "Dunkirk" and "Oppenheimer," which both largely take place during the war. This idea is borne out within "Oppenheimer," as the film's structure — bouncing back and forth between the mid-1930s and the late 1950s, using the 1940s as its center — tends to resemble a "temporal pincer movement," with the creation of the atomic bomb an event whose gravity sucks everything towards it.

Apocalypse when?

Another theme recurring in Nolan's work is the idea of an impending apocalypse or armageddon. In some instances, this apocalypse is literal: in "Interstellar," the citizens of Earth must find a way to survive the dying planet, in "Batman Begins" and "The Dark Knight Rises," Gotham City is narrowly saved from total destruction, in "Tenet," the unseen people of the apocalyptic future wage war on the past that created it, and in "Oppenheimer," the physicist foresees the small but significant possibility that testing the atomic bomb may literally destroy the world.

In other instances, this apocalypse is more metaphorical and internal, as seen in the moral rot of the characters of "Following," the loss of identity and purpose for the memory-loss protagonist of "Memento," the loss of the characters' sense of self in "The Prestige," the potential corruption of Gotham's soul in "The Dark Knight," and the total loss of reality in "Inception."

All of this stems from Nolan's childhood during the final years of the Cold War being fraught with anxiety over mutually assured destruction. As he told USA Today, "My friends and I thought we would die in a nuclear Armageddon at some point in our lives." It's fitting that Nolan has found a way through his art to face the man indirectly responsible for those deep-seated fears.

A guilty hero

Perhaps the most major recurring feature in all of Christopher Nolan's films is the idea of a main character weighed down by an enormous sense of guilt. This may have stemmed from Nolan's initial trilogy of films ("Following," "Memento" and "Insomnia") being rooted in the traditions and tropes of film noir, a genre that includes flawed and moody protagonists as a prerequisite.

It certainly continued to crop up in various ways in all of his films after that, whether it was about a self-appointed superhero who couldn't save his parents (and maybe not even his city) from being victims of corruption, or a husband mourning his role in the loss of his wife, or a father knowingly leaving his family (especially his daughter) behind forever, or an army having to retreat.

In this way, J. Robert Oppenheimer is the ultimate Nolanesque flawed hero: a man who sought to unlock secrets of the universe and was only too successful, resulting in the realization that he may have doomed himself if not his entire species. He even has a "dead wife" to mourn (arguably the most memed Nolan trope) in the form of the suicidal Jean Tatlock (played by Florence Pugh). Just as "Inception" metaphorically details the efforts behind filmmaking, wherein a team puts together a spectacular narrative with the intention of eliciting an emotional response from an audience, it's possible that Nolan sees a similar kinship within Oppenheimer, where the scientists stand in for artists who don't realize where the corporate and political interests of those who've employed them will take their creation until it's far too late.

Family ties

Yet there may be another deeper, darker, and more personal connection between Oppenheimer and Nolan then merely a metaphorical kinship. As it turns out, Nolan has both a younger brother (Jonathan, a screenwriter and producer of numerous films and TV) and an elder brother, Matthew. This latter brother is barely spoken about by Nolan in interviews and the like, in large part because Matthew has been accused of making his living as a real-life hitman.

Further complicating this connection is the possibility that, according to court records dug up by the site How Stuff Works, Matthew Nolan used an alias to make contact with his alleged target, going by the name "Matthew Oppenheimer." A coincidence, maybe, due to all the Nolan brothers growing up in the same household, with Matthew paying somewhat dark tribute to the anxieties his younger brother harbored since he was a kid.

Still, with this information, it's easy to see "Oppenheimer" as not just Nolan's latest film but as a work of destiny, something the filmmaker had to finally face up to and address. Nolan's complicated family history turns him into his own Oppenheimer-esque guilty hero, a man burdened with knowledge of things he cannot change, who has a brother he must find a way to embrace as well as deal with. In addition, Nolan's own obsessions with theoretical physics, the future, and the love of his family have him seeing visions of potential, encroaching destruction not unlike the man who built the bomb nor his own childhood self. For all these reasons and more, "Oppenheimer" is — and may remain — the ultimate Nolan film.