Mary And Max Uses Stop-Motion To Find Friendship In A Cruel World

(Welcome to Animation Celebration, a recurring feature where we explore the limitless possibilities of animation as a medium. In this edition: "Mary & Max.")

The internet allows us the ability to connect with people in ways that were previously unthinkable, and while it is still ridiculously difficult to make a true, human connection, the lack of geographical or physical barriers has certainly made it a heck of a lot easier. Social media has given us the opportunity to "reach out and touch" people from opposite ends of the globe, which for many people, can be the difference between life and death. Sometimes I find myself absorbed by the existential worry of how marginalized, disabled, or isolated individuals found community before the advent of the internet. Did they ever feel seen? Did they ever feel like someone else truly understood them for who they are? Did they ever know that they weren't alone in the world?

The 2009 Australian stop-motion dramedy "Mary and Max" is about two unlikely pen pals over the course of 20 years. When the friends first connect, Mary (Toni Collette) is a lonely, chubby elementary school-aged girl in Australia, who befriends Max (Philip Seymour Hoffman) a middle-aged Jewish man on the Autism spectrum living in New York City. The film was written and directed by Adam Elliot, and based on his own personal friendship with a pen pal he wrote to for over two decades.

Shot using over 130 different sets, over 200 puppets, and 475 miniature props (including a fully-functional typewriter sized down for a stop-motion puppet), "Mary and Max" captures the beauty and heartbreak of existence by exploring themes of friendship, addiction, childhood neglect, bullying, loneliness, mental illness, isolation, suicidal ideations, neurodivergency, and living in a fatphobic world.

The randomness of finding a friend

The character designs of "Mary and Max" feel like a cross between the precision of stop-motion legend Henry Selick, and the childlike wonder found in the claymation features of Aardman Animations, the folks behind the "Wallace & Gromit" movies. By utilizing an aesthetic that feels reminiscent of the films so many of us grew up watching as children and injecting it with the harsh, bleak realities of existence through its story and color palette, "Mary and Max" is a reminder that the world can be tough for everyone, regardless of age.

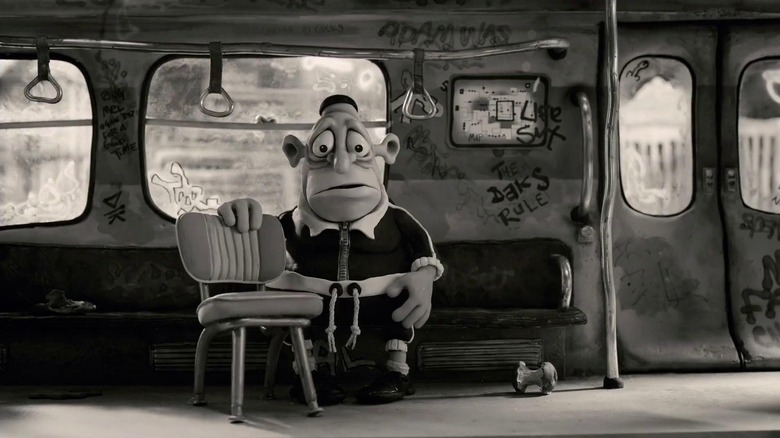

Toni Collette and Philip Seymour Hoffman deliver two of the strongest voiceover performances from non-exclusive voiceover artists as the titular characters, finding the perfect balance of bitter humor and unexpected whimsy to make them both fully realized people. As the film covers such a long stretch of time, it's fascinating to hear the way their voices age and change as they grow and evolve with each passing year. There's a dry writ present throughout each scene, with Mary's sepia-toned suburban life and Max's black-and-white gritty city isolation both treated with the same gravity in terms of how one way of living isn't necessarily "better" than the other.

Mary's decision to write to Max is out of desperation. She's bullied at school and looking for absolutely anyone to treat her with kindness, and it was only by a random coincidence of the universe that Max was the address she happened upon, a man who was also in desperate need of a friend. Through a shared love of chocolates and a "Smurfs"-like series called "The Noblets," the two find common ground in a world that treats them with cruelty.

Dissecting social issues

Max learns at one point that he has Asperger's syndrome. As this is a film from 2009, it's important to note that this distinction of being on the autism spectrum was reframed in 2013, as the name derives from a Nazi doctor who used the distinction to determine who was "worthy" enough to be spared from euthanasia during the Holocaust. Max's diagnosis is life-changing because he suddenly has an understanding of why he's struggled to adjust to a neurotypical society for most of his life. It's what inspires him to write back to Mary after years of avoiding her after she asked him a question about love that triggered a severe anxiety attack that led to him being institutionalized for eight months.

When Mary finally hears from her long-lost friend once again, she's ecstatic. She eventually attends university, has a birthmark that has caused her great pain surgically removed, and decides to study psychology, using Max and his autism spectrum disorder as her case study (without his consent). The two have made an undeniable impact on one another's lives, and have remained a constant, even with the years apart, as they both lost friends and loved ones (often in hilariously tragic ways ... like a jetpack incident).

There are plenty of moments of optimism throughout their decades-long friendship, but "Mary and Max" poses some deeply difficult questions, often regarding mortality, identity, and how we all find ways to cope with the weight of existence in an unfair (by design) society. The look of "Mary and Max" screams "adorable," but the story shouts back "devastation."

The movie The Whale wishes it was

I couldn't help but think about "Mary and Max" while watching Darren Aronofsky's fatness-as-trauma-porn drama, "The Whale." Max's fatness is treated by those around him as something in need of "fixing," the same way his mental illness and neurodivergency are pathologized. He is diagnosed with obesity in the same way that he is diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder, but is given autonomy in a way that Brendan Fraser's Charlie is never afforded in "The Whale."

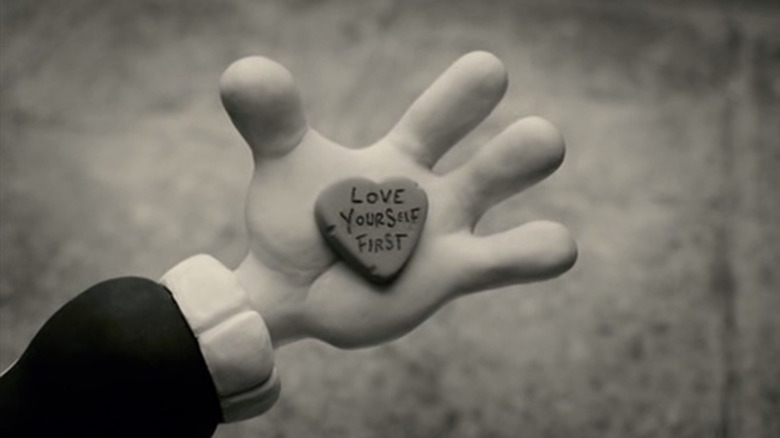

Max shows up to Overeaters Anonymous meetings at the recommendation of his therapist, but quite frankly, doesn't buy into their bulls**t. His fatness has never been an issue for him, only for those around him who can't get over their own fatphobic ways of thinking. Max's health issues have nothing to do with his weight, and everything to do with his declining mental health and the way society has mistreated him for reasons beyond his control. "Mary and Max" doesn't try to moralize his body or display it in cartoonish ways.

Mary starts off as a chubby child and is ridiculed by her mother for her size, and as an adult, Mary is shown as slimmer. She saves up money to remove her birthmark, clearly believing that physical changes will directly change how she feels about herself in the world ... but it doesn't because there's no magic wand that can make a physical change miraculously transform your feelings of self-worth. Even with his size, Max is able to fulfill all of his dreams, because he worked on loving himself and finding forgiveness in the world. The film ends similarly to "The Whale," and despite sharing similarly devastating themes, "Mary and Max" is not a tragedy, it's a tale of humanity.