Wendell And Wild Director Henry Selick Knows Stop-Motion Animation Will Never Die [Set Visit]

It's a typically rainy Portland, Oregon day in April 2022 when we arrive at the nondescript studio. Tucked away in an industrial park on the edge of the city, it looks like a bland warehouse space. It certainly does not look like a building where a crew of artists and animators, led by one of the true geniuses of the medium, have spent the past few years toiling away on a stop-motion movie about demons voiced by two of the funniest people on the planet, and the young girl they rope into their scheme to make it rich in the world of the living. It certainly doesn't look like the headquarters for filmmaker Henry Selick, the director of "The Nightmare Before Christmas" and "Coraline," who, armed with a Netflix budget, has endured not only the inherent difficulties of making a stop-motion animated movie but a deadly pandemic and freak weather that put the entire production at risk.

But once we enter the building, masked and tested for Covid, we start to see the little details. The weird stuff. The fun stuff. Boxes piled high with very specific labels. Graveyard sets. Character costumes. Alternate hair. The signs of an entire horror-tinged world, populated by puppets and brought to life frame-by-frame by animators over the course of years, is being boxed up as production winds down.

"Wendell and Wild" is in its final days, and director Henry Selick is here to share it with us. A simultaneously gracious and nervous host, the filmmaker sounds eager to finally talk about what he's been doing with the past five years of his life. And what this film, and his work, might mean for the future of stop-motion animation in a landscape dominated by CG animation.

A taste for imperfection

There's a phrase Selick uses throughout the day whenever he finds himself talking about modern animation, specifically the digital output that's become the default over the past 20-plus years: "lubricated imagery." He has nothing negative to say about the actual films of studios like Disney and Pixar, but he admits they blend together for him, having adopted the same visual aesthetic across the board. "They are all virtually the same in my mind," he tells us as we gather around a conference table. Those films are too clean, too perfect. He likes stop-motion because it's not perfect. He wants the audience to see the mistakes. He tells us:

"The audience has to work a little more for them to believe in what they're seeing. Not so much that it feels like work, but I think they become more invested, if they make the effort and I want them to. Then the film becomes more a part of them."

That may sound a little wild to some moviegoers in the era of digital animation that can create cityscapes and African savannahs that look nothing short of photo-realistic, but it makes perfect sense for one of the masters of moving puppets millimeter by millimeter to create the illusion of movement. You don't make stop-motion animation if you're not the kind of person who operates off the beaten track by default.

It's strong magic

And off-path is where Selick lives. Sure, he's made some of the most beloved animated movies of the past couple decades, but those films weren't always embraced out of the gate. Time has been kind to his work, and Selick argues that time is kind to stop-motion animation in general.

"The good ones, the films last," Selick says of stop-motion. "They don't get old because they're already old. It's already an ancient technology. And it's like magic, but I think it's strong magic."

There's no bitterness in Selick's voice when he notes that the billions of dollars in merchandising Disney has made off "The Nightmare Before Christmas" over the years has not trickled down to him ("No, I don't get any of that. But Tim Burton sure does."), but that movie proves his point. Only a modest success upon release, the film dug in its heels and became a modern classic beloved by millions, and a cornerstone Disney property. To put it mildly, Selick was ahead of the curve with that one. So when he pitches a project like "Wendell and Wild," which feels built on similarly offbeat sensibilities and gallows humor, you would hope someone would listen.

And in this case, Netflix listened.

The Key and Peele of it all

"Wendell and Wild" was born when Selick wrote a story inspired by his two young sons. They were little hellraisers, which meant they were the perfect inspiration for a tale about two squabbling demon brothers. The story didn't lead to anything and was filed away, unpublished. Years passed. And then Selick saw "Key and Peele," the acclaimed sketch comedy series starring Keegan-Michael Key and Jordan Peele, and knew he had found his demons. "What the hell, I'll reach out," Selick decided.

The result: immediate interest from the duo, particularly Peele, who requested a face-to-face meeting. This was before Peele became an Oscar-winning filmmaker, before the world knew him to be a cinephile with a deep well of knowledge about film history and filmmaking. And once he saw the world Selick was building, Peele got involved creatively, helping to write the screenplay and serving as a producer. Although Selick does not go into detail, he notes that Peele helped shape the story into its final form:

"There's a lot of great things that Jordan contributed. All the basic characters were there, but he felt that the protagonist should be different. He [added] all sorts of great things to characters in the story."

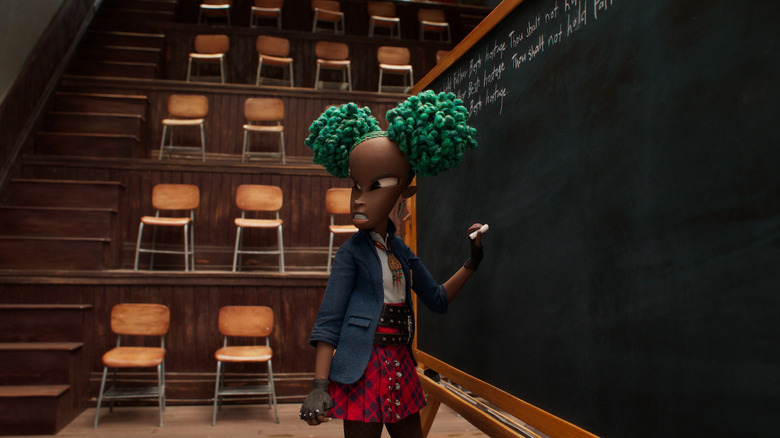

The protagonist of "Wendell and Wild" is an angry young Black punk teenager who lost her parents and finds herself wrapped up with two demons who have escaped their hellish domain, which certainly suggests Peele's touch. The character of Kat (voiced by Lyric Ross), with her green dyed hair and Blaxploitation fashion and "f*** off attitude," feels like someone who would've been right at home in Peele productions like "Get Out," "Us," or "Nope."

But even with Key and Peele signed up to voice his leads, "Wendell and Wild' wasn't a sure thing. In fact, Selick wryly remembers Peele urging them to pitch the project before "Get Out" hit theaters in 2017, worried the film would bomb and make his involvement a hindrance rather than an asset. But then "Get Out" was a massive critical and financial hit, and an Oscar-winner to boot. "All the doors were open," Selick says.

And Netflix locked them down, especially after the studio showed their support for the film to remain stop-motion. "It's always been the stepchild of the animation industry," Selick notes.

A handmade world

The surprising thing about the set of a stop-motion movie is how everything feels so much smaller than you'd think, while also looking utterly massive. A sprawling graveyard set fills an entire room, but the reduced scale of those hills and trees feels downright surreal. A demonic theme park is as intricate and detailed as anything you've ever seen, but it could easily fit on an especially large coffee table. To see a film crew gather around a stop-motion set is to watch human-shaped Kaiju loom over words of their creation. To see them interact with the puppets that become the film's characters rattles the brain. Those puppets (those people?) look too detailed and too full of life, even when stationary, to be picked up and carried around like a prop.

And these sets, these characters, feel emblematic of Selick's preference for letting imperfections actively shine onscreen. Found material is utilized to create the locations (a ratty old rug became the foundation of that graveyard set). The "seam lines" are left on the puppet heads, an ongoing reminder that animators swap in and out upper and lower faceplates to animate changes in emotion and expression. Selick notes that the latter is a cost-saving opportunity, one he borrowed after watching the stop-motion film "Anomalisa," but he also thinks perfection, that "lubricated imagery," is overrated. "I think people will watch and in five minutes [the seam lines] disappear because you get invested in the characters," he says.

So, who are those characters? There's Wendell and Wild, voiced by Key and Peele, two purple-skinned demons from an afterlife where the "souls of the danged," people who were pretty crummy but don't deserve the full-on Hell treatment, are cursed to an existence of discomfort in a dangerous theme park called "the Scream Fair," which is built on the belly of a 300-foot-tall demonic entity named Buffalo Belzer (voiced Ving Rhames). Wendell and Wild — one brother wily and ambitious, the other dim-witted — find themselves demoted to the worst task on Buffalo Belzer's body: continuously re-planting their master's hair plugs. So when the opportunity arises to escape to the mortal world, and use their knowledge of the afterlife to make a living resurrecting the dead, they seize it.

And that's where Kat, orphaned and angry and putting up with her existence in Catholic school, enters the picture. And there's also a possessed teddy bear named Bearzebub, a Donald Trump/Boris Johnson-inspired villain threatening the town where the action takes place, and seemingly dozens of other characters, ranging from students to nuns to social workers to church ladies. When we're taken to a room to meet the cast, so to speak, it's astonishing. Like with some of the best-animated characters, one glance at these folks tells you everything you need to know about them. But these characters don't leap off any page — they exist as puppets in actual space, somehow both too big and too small. And after a few minutes of examining them, you stop noticing the seam lines on their faces.

The first footage

Making a stop-motion animated movie under any circumstances is grueling, painstaking work. You work all day for seconds of footage in an industry increasingly less willing to bet on unsure things ... and a non-CG animated movie is about as unsure as you can get these days. But fate threw additional speed bumps at "Wendell and Wild." A worldwide pandemic that shut production down until proper safety measures were set (Netflix continued to pay the crew as they sat and waited). Dire climate emergencies sent Portland into a heatwave, complete with forest fires that came close enough to the set to require a "puppet rescue," with members of the crew literally loading their cast of characters into their cars and driving them to safety. "If the studio burns, we can rebuild the sets, but we can't replace those puppets," Selick says.

There is a haze of fatigue over the set of "Wendell and Wild" during our visit. Much of the crew had already wrapped and had moved onto other projects (Portland, a hub for stop-motion animation, was also hosting Netflix's "Pinnochio" and a top-secret LAIKA production). The offices are literally being packed up as we tour them. Selick looks like he could use a month's worth of good night's sleeps. The film is practically in the can, but even a handmade stop-motion movie needs months of tireless post-production.

At the end of our visit, Selick takes us to a screening room on the second floor of the studio, and we watch the first footage of "Wendell and Wild." It's just a few minutes, and it's very unfinished — Selick is visibly nervous, apologizing for the rough state of what we're about to see.

But even in its unfinished state, footage from "Wendell and Wild" ignites the imagination. Characters in the demon world are built to resemble 3D recreations of 2D designs, looking like walking paper craft characters (closely capturing the work of character designer Pablo Lobato). In the mortal world, the animation closely resembles the more polished visual style of Selick's own "Coraline" — characters move with weight and grace, their 3D-printed faces containing so much emotion that you don't think about the seam lines. And yes, the biggest draw for many folks does deliver: Wendell and Wild themselves are classic Keegan-Michael Key and Jordan Peele archetypes, bumbling, ambitious doofuses who love to drive each other crazy.

It's in this unfinished state that you can appreciate just how much more work has to be done. For example, a whirlwind introduction to the afterlife features ghostly phantom characters who fly in from offscreen, still supported by the metallic C-stands that will be digitally erased in post-production. Just because "Wendell and Wild" is using "old magic" doesn't mean it's not taking advantage of the new magic, too.

'Making movies this way, it's insane'

Henry Selick, synonymous with modern stop-motion animation for an entire generation of movie fans, is nearly 70. But he's not done yet. He's working on a project based on a Neil Gaiman book ("His best one") and he's hoping to resurrect "The Shadow King," a project Disney axed because it was "just too weird for them." And he's convinced stop-motion animation, while certainly a rare breed, isn't a dying breed.

"There's always more stop-motion animators," Selick tells us. "[Kids], they love touching things." According to him, the form is here to stay:

"There will always be animators because it's a way to make films very personal. Not everyone wants to work at the keyboard all the time. I Don't think that's ever going away. We'll find the animators"

Selick thinks highly of other filmmakers currently working in stop-motion, calling out the animated films of Wes Anderson ("He is probably the greatest production designer in history"). And he seems hopeful that Netflix will continue to embrace stop-motion, unaware at the time that Netflix's animation division was literally days away from a crisis that could threaten the optimism and hope he expresses throughout the day. He praises Netflix for taking bigger risks than anyone else in the industry, citing their belief in animation as a medium. Months later, it can't help but feel bittersweet.

But "Wendell and Wild" got made, and it got made during a window where one of the biggest studios in Hollywood was willing to take a chance on a batty, horror-tinged stop-motion movie from a director who is literally dedicated to imperfection. And Selick himself knows this whole thing is downright bonkers:

"Making movies this way, it's insane. Let's admit it. Movies a frame at a time. But at the heart of it, for me, it's the most magical way to make a film. It's the oldest form of filmmaking, when objects would jump around. Film's the magic disappearing hat. Things from the 1890s. The fact that we can gather a tribe who all believes in this approach to filmmaking, it's a miracle."

"Wendell and Wild" hits Netflix on October 28, 2022.