Cowboy Bebop Anime Creator Shinichiro Watanabe Was Not A Fan Of The Netflix Adaptation

It's been over a year since Netflix's live-action adaptation of "Cowboy Bebop" began then ended, but it was clear the project was a misfire long before now. The series was canceled three weeks after premiere, lightning speed even by Netflix standards. It turns out that one of those disappointed was the anime's primary creator, animation director Shinichirō Watanabe (he and his team are collectively credited as the creator "Hajime Yatate").

Before Netflix's "Cowboy Bebop" premiered, Watanabe revealed he'd been asked for his input: "I read the initial concept and provided my opinions, but I'm not sure if they will be reflected in the final product." He added that his suggestions being ignored would "leave a bad taste in [his] mouth," but to avoid making the crew's jobs tougher, he would simply hope it "turn[ed] out good." His hopes weren't met.

Watanabe recently spoke with Forbes. Topics ranged from how he entered the anime industry to his later works like "Samurai Champloo" and "Space Dandy." But he was also asked for his thoughts on Netflix's "Cowboy Bebop." Watanabe revealed Netflix sent him a preview of the series; he wasn't able to watch anything beyond the first scene:

"I stopped there and so only saw that opening scene. It was clearly not 'Cowboy Bebop' and I realized at that point that if I wasn't involved, it would not be 'Cowboy Bebop.' I felt that maybe I should have done this. Although the value of the original anime is somehow far higher now."

Indeed, the best part of this whole episode is that Netflix added the "Cowboy Bebop" anime to its streaming library. So, why did Watanabe think the live-action series isn't even an imitation of his anime?

The opening

The opening scene Watanabe mentions is an abridged version of the opening for the "Cowboy Bebop" movie, "Knockin' on Heaven's Door" (Watanabe directed said film). In both scenes, our anti-heroes Spike Spiegel and Jet Black are capturing a gang with bounties on their heads. Spike wanders into the scene, wearing headphones and cool as a cucumber, before they get caught in a stand-off.

In the movie, the setting is a convenience store, but in the Netflix version it's Watanabe Casino — the director either didn't notice or didn't care for the compliment. The scene includes verbatim dialogue from the movie, but that just makes it feel uncanny, not faithful. Rather than the fluid fight choreography of the anime, with often unbroken coverage, the Netflix show has frequent cuts and close-ups to hide the obvious staging of the action.

Poverty and corrupt corporations were themes of the original "Cowboy Bebop," but in the Netflix version, the leader of the bounties says out loud multiple times how much he hates big corporations. Rather than trusting its audience to pick up on themes, the Netflix "Bebop" tries to hold their hand and spell it out with dialogue (more on that later).

The scene diverges when one of the crooks blows a hole in the casino's hull. From there, the scene homages the climax of "Aliens," with the characters holding on as the vacuum of space grabs them. Apparently, the scene in "Knockin' On Heaven's Door" wasn't sci-fi enough.

By turning off the series after this scene, Watanabe avoided the worst the show had to offer.

Faye Valentine

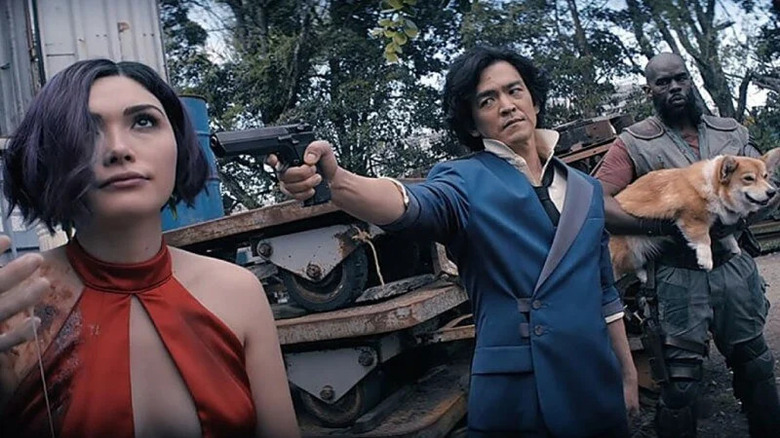

Despite Watanabe's displeasure with their introduction, I'd argue Spike and Jet come through as the most intact of the main characters. John Cho and Mustafa Shakir, respectively, are both solid casting. Even if they're saddled with poor writing, the vague outlines of their anime characterizations are still there. The same cannot be said of Faye Valentine (played by Daniella Pineda).

Faye is a screw-up — and that's why we love her. She's clever in a pinch and a good fighter, but she also bites off more than she can chew. After all, she is a gambling addict (something the Netflix show omits). But that isn't all there is to her.

An amnesiac who doesn't even know her real name, Faye preaches about the survival of the fittest, but really, she's lonely. She won't even admit her longing for connection to herself, because it got her burned in the past. Now, she's convinced the only way to live is to backstab others before they can backstab her. That's why she wears the guise of a femme fatale.

None of this is in the Netflix version. Instead, Faye is a generic kick-ass girl-boss who speaks in "Buffy" leftovers like, "Welcome to the ouch, motherf***ers!" (Anime Faye would die from secondhand embarrassment if she heard someone say that).

Vicious

Faye isn't even the worst that Netflix's "Cowboy Bebop" has to offer. That would be Vicious (Alex Hassell), a captain in the Red Dragon crime syndicate and Spike's friend-turned-enemy.

Vicious in the anime was a nihilistic void of humanity. He was so scary because he was an enigmatic and infrequent presence. In the Netflix series, he's a petulant mustache-twirler, often wearing a goofy grin. In a foolish attempt at serialization, the series also turns him into an overarching villain who pops up in every episode.

Alex Hassell has none of the chilly menace that Norio Wakamoto and Skip Stellrecht (in Animaze's acclaimed English dub) both brought to the part of Vicious. Instead, he offers haughty condescension and screams half his lines. Plus, that flowing white wig simply doesn't go with Hassell's face.

The series also tries to "explain" Vicious' name by revealing it's a pseudonym. Completing the schema, Spike was once called "Fearless." Here we encounter a frequent problem with modern genre writing: in trying to rationalize over-the-top elements, you just underline the silliness.

The wrong mood

The problems with the characterizations in Netflix's "Cowboy Bebop" go back to a root problem with its approach. The anime was earnestly cool; it presented its world seriously, and the comedy was always about laughing with the series, not at it. But that's not in fashion nowadays. Instead, entertainment pokes fun at itself with smarmy, wink-wink dialogue. Adding that writing style to "Cowboy Bebop" couldn't be more ill-fitting and results in some truly atrocious dialogue.

But also, dialogue isn't what drives "Cowboy Bebop." The characters never discuss their feelings aloud — they're not those kinds of people. Instead, you have to glean those feelings through their actions. The anime similarly trusts you to piece Spike's past together with largely silent, visually-driven flashbacks.

The most important part of the sound in "Cowboy Bebop" is the music, not the dialogue. Yoko Kanno's score is alternatively jazzy, thrilling, and bittersweet — it's what gives the anime its trademark ennui. I find turning "Cowboy Bebop" into a manga, a medium without sound, was just as wrong-headed as the Netflix adaptation because there's no music there.

The Netflix show at least grasped the music's importance, even reusing Kanno's score, but it never relies on it the same way as the anime. It feels more like wallpaper than a mood setter. "Cowboy Bebop" was willing to be quiet and let Kanno set the mood, but in the Netflix show, they've always got to get to the next joke.

Watanabe may feel he should've been more involved with Netflix's "Cowboy Bebop," but the truth is he already gave us all he wanted to from the story, complete with a perfect closing note. Trying to change a classic, and taking it out of the medium which made it sing so beautifully, was never going to work.