How High Noon Took Aim At The Hollywood Blacklist

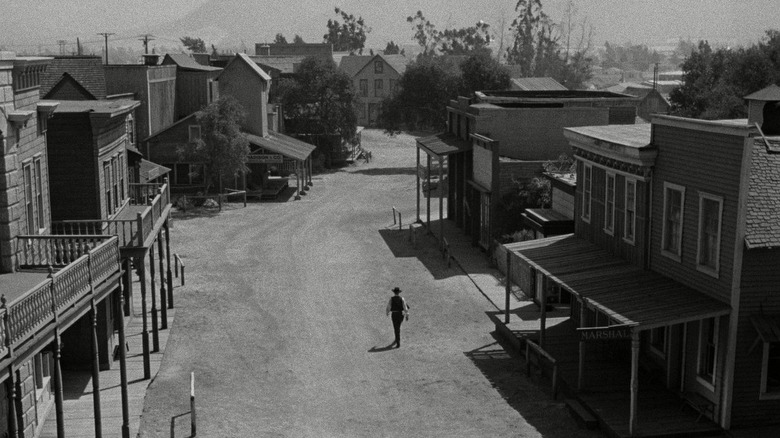

Among the classic westerns of the Golden Age of Hollywood, "High Noon" stands tall in its simplicity. Aging marshal Will Kane (Gary Cooper) has retired, ready to start afresh with his new bride, played by Grace Kelly in her breakthrough role. Before he has had a chance to say his goodbyes and leave town, word arrives that an outlaw he sent to prison is coming in on the noon train with his gang, seeking revenge. His sense of duty and pride won't let him run scared, even though it's not his job anymore, and he tries to raise a posse to confront the bad guys. However, no one is prepared to stick their neck out, apart from the town drunk and a kid who admires Kane. He refuses their assistance and has no choice but to stride out to face the killers alone.

Told almost in real-time, Fred Zinneman's celebrated western makes the most of its ticking-bomb set-up, frequently casting anxious looks at the clock as midday approaches, building sweaty tension as Kane goes about the town seeking help, his rugged features determined but becoming slightly more downcast at each rejection. The premise is so concise that, like "Catch-22," its title has entered our lexicon for a specific situation: The moment of truth when an impending situation has become impossible to avoid.

For all its streamlined simplicity, "High Noon" masks layers of subtext and allegory that caused controversy during a highly politically-charged moment in America's early post-war history. Maybe that shouldn't come as any surprise, because screenwriter Carl Foreman had his sights set firmly on the powers that ruined his Hollywood career and forced him into exile from the States.

The Second Red Scare and the Hollywood blacklist

During World War II, the United States and the Soviet Union put aside ideological differences to form an uneasy alliance against the Third Reich. Once the conflict was over, hostilities resumed with the dawn of the Cold War. Some key figures in American politics, including Richard Nixon and Senator Joseph McCarthy, were increasingly fearful of the threat posed by the Russians now they had expanded their sphere of influence to countries behind the Iron Curtain and developed their own nuclear weapons.

The House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), established in 1938, investigated hundreds of people suspected of Communist allegiances in the '40s and '50s, during a period known as the Second Red Scare. Sometimes a mere rumor was enough for a person to get hauled up in front of the committee, where they were expected to renounce their alleged Communist leanings and point the finger at other potential conspirators in a supposed Red plot to destroy American values from within.

Tinseltown attracted suspicion as a possible hotbed of subversive activity, and studios drew up the Hollywood Blacklist to cover their own backsides by showing how patriotic they were. Over 500 people found themselves on the list, ending many careers and driving several individuals to despair, dying by suicide.

One of the most high-profile cases was that of the Hollywood Ten. In 1947, ten movie industry figures including screenwriter Dalton Trumbo ("Roman Holiday") were subpoenaed for the first public hearings but refused to testify. This resulted in a prison sentence and a place on the blacklist. Many never worked again in Hollywood, although Trumbo continued writing screenplays under various pseudonyms.

Carl Foreman faces the House Un-American Activities Committee

As a former member of the American Communist Party, "High Noon" screenwriter Carl Foreman's case was more complicated. Prior to working on the script, he received two Oscar nominations for "Champion" and "The Men," and his success attracted the scrutiny of the HUAC. Although Zinneman's classic western would eventually make it number three, his involvement in the picture became increasingly precarious when he was summoned to stand before the committee in the middle of the film shoot.

Under such pressure, Foreman started reworking his "High Noon" screenplay, now feeling like the lone stand-up guy abandoned by his friends, with the HUAC's gunmen coming for him. He said (via Vanity Fair):

"As I was writing the screenplay, it became insane, because life was mirroring art and art was mirroring life. It was all happening at the same time. I became that guy. I became the Gary Cooper character."

With his screenwriter under the baleful glare of the Committee, Foreman's close friend, business partner, and producer Stanley Kramer started getting very nervous. He was initially supportive of his friend, but he'd just signed a big five-picture contract with Colombia and another partner warned that Foreman's refusal to cooperate with the committee might scupper the deal. Perhaps Kramer had a good reason to feel anxious; as a Liberal, he already had a reputation for "being sympathetic to Communism," and Foreman's trial could implicate him next.

Foreman bravely stood his ground against the committee as his supporters, including Gary Cooper, fell away one by one. But it was only a matter of time before the allegations destroyed his professional standing in Hollywood.

Gary Cooper makes a stand

With only a limited budget, landing Gary Cooper to play Will Kane was a major coup for Kramer and his production company. Now aged 50, Cooper's star was on the wane after a string of successful movies in the '40s, including an Oscar-winning turn in "Sergeant York." He was still a big name capable of carrying the picture and raising its profile, even though both Foreman and Kramer regarded him as a relic of the old studio system.

Perhaps surprisingly, Cooper also supported Foreman during his travails at first. The actor was a Conservative Republican and a charter member of the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals (MPA), a parallel organization to the HUAC which set its sights on weeding out Communist and Fascist subversives in the film industry. Apart from Cooper, it counted big Hollywood names like John Wayne, Walt Disney, and John Ford among its number.

Nevertheless, Cooper had great respect for Foreman and offered to fight the screenwriter's corner before the Committee, before his lawyer persuaded him it wasn't such a good idea. Later, after Kramer and his associates got together to kick Foreman off "High Noon," Cooper initially agreed to invest in Foreman's own production company and star in its first feature. However, pressure from rightwing gossip columnists, the studios, and the MPA was too much for even a person of Cooper's high standing. Queries were raised about why an All-American legend like him would want to go into business with a suspected Communist, and he backed away from the partnership.

The end result

With his Hollywood career shot down in flames, Carl Foreman moved to England and carried on screenwriting. He never spoke to his old friend Stanley Kramer again. He still received an Oscar nomination for "High Noon," and two more for "The Guns of Navarone" and "Young Winston." He was able to return to the States in 1975, and posthumously received an Academy Award for his work on "The Bridge on the River Kwai."

"High Noon" was a box office success, although some audiences and critics were confused by its radical departure from the usual chases and shootouts expected in a Hollywood western. Cooper is majestic as Kane, bringing a quiet world-weary gravitas to the role of an honorable man left high and dry by the community he had served for so long, with no choice but to face the killers alone.

Nowadays, the film is regarded as one of the first revisionist westerns, and Red-bashing John Wayne sniffed out its subversive themes. In his infamous Playboy interview in 1971 (via The Wrap), he claimed it was "the most un-American thing I've seen in my whole life" and said, "I'll never regret having helped Carl Foreman out of this country."

How strongly Foreman's allegory comes across is a matter for debate. Much like another genre classic of the '50s, "Invasion of the Body Snatchers," it could be just as easily read as anti-Communist as anti-McCarthyism, with the lone lawman representing the vigilant Senator facing the marauding threat of the Commies.

Putting aside the political aspect of "High Noon," perhaps another reason for its enduring popularity is that it's simply a universal tale that almost anyone can relate to. Who hasn't felt at times like one person standing alone with the courage to do the right thing?