The True Meaning Of The Human Centipede Movies

When Tom Six's horror freakout "The Human Centipede (First Sequence)" was released in 2009, it was met with much disgust and ballyhoo. The poster boasted that the film was "100% medically accurate," something that no movie poster should ever boast.

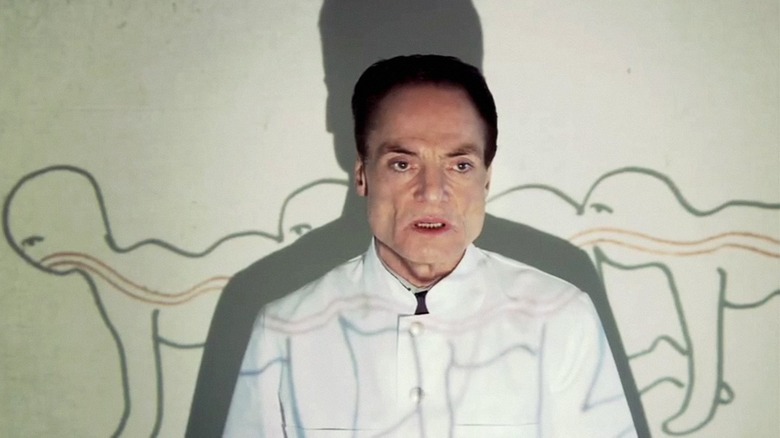

The premise was wild and gross and repelled prudes while attracting seekers of the extreme. A mad scientist named Dr. Josef Heiter (Dieter Laser) — clearly inspired by Josef Mengele — kidnaps three hapless tourists (Ashlynn Yennie, Ashley C. Williams, and Akihiro Kitamura) and announces his dark plan while they are strapped to gurneys in his basement. Dr. Heiter intends to surgically connect the three people via their alimentary canals. He will connect one person's face to the previous person's anus, and remove tendons in their knees, forcing them to crawl. In so doing, he will create a human centipede. There is no stated reason for his experiment.

Audiences who saw "The Human Centipede" were appropriately grossed out. The film wasn't so much a film as a geek show, made to test the endurance of whoever dared buy a ticket. It was to fall into a camp next to "Faces of Death" or the various Mondo shockumentaries of the 1970s. And while there is a certain grindhouse integrity to making a film that serves entirely as an endurance test — it takes chutzpah to be so deliberately repellent — it would have been nice if "The Human Centipede" also functioned as, y'know, a movie. As it stands, it barely qualifies as cinema.

Full Sequence

When Six followed up his "(First Sequence)" with "The Human Centipede 2 (Full Sequence)" in 2011, he outdid himself in his efforts to be as nauseating as possible. In the world of "(Full Sequence)," the original "Human Centipede" is a mere fictional feature film that, with its twisted premise, seems to have inspired a mentally ill recluse name Martin (the gloriously off-putting Laurence R. Harvey) into making a human centipede of his own. Not to be outdone by the three-person centipede of Dr. Heiter, however, Martin kidnaps twelve people — including Ashlynn Yennie, playing herself — and assembles them in a filthy warehouse using scissors, duct tape, twine, and injected laxatives. His process is filmed in gruesome detail. The film features forced tooth removal, and a scene with a pregnant woman that should remain tactfully undescribed.

"(Full Sequence)" is one of the most revolting films available to the public, and that is not meant affectionately. It sought to be repellent, and boy howdy, is it ever. There is no longer a pretense that the "Human Centipede" series was meant to function as traditional films. These are only meant to function as dares, as tests of how far out of the lines Six would allow himself to color. If a viewer has remained incurious, one can hardly blame them.

But with "(Full Sequence)" a curious commentary began to emerge. There is a metanarrative at work here. After all "The Human Centipede" is only a movie in the sequel.

The Anxiety of Influence

At first glance, the metanarrative points to director Six bragging about the success — and the disgust — born of his 2009 film. Like a kid eating a second bug, he is childishly proud of the fact that his first bug-eating caused other kids to barf. The metanarrative could easily be construed as a form of adolescent vanity.

But Six, perhaps unintentionally, has made a comment on the way we consume media. Like a dark mirror to Jean-Luc Godard's "Breathless," "(Full Sequence)" stars a character who takes his behavior cues from the art of others. Influenced by what he sees on a screen, both Martin and Godard's Jean-Paul Belmondo aim to construct a new kind of living art wherein they themselves are real-life movie characters. Belmondo takes his behavioral cues from "cool" icons like Humphrey Bogart, and fashionably sports fedoras and cigarettes. Martin takes his cues from "The Human Centipede," and unfashionably kidnaps innocents and connects their faces to others' bottoms.

Six, now several generations removed from "Breathless," seems to be skewering the very idea of cinematic influence. Audiences and filmmakers who take their cues from earlier films are now merely victims of cynical filmmakers who have nothing interesting to say. One may be charmed by the Hitchcock light of Brian De Palma, for instance, but to Six's eyes, that's no different from having your face strapped to another person and being forcefed their, uh, product.

Final Sequence

One might bristle at the notion that all influence is a negative thing. After all, every piece of art stands as a criticism, a commentary on the art that came before it. Literary critic Harold Bloom referred to this as the Anxiety of Influence. Six seems to be criticizing something far more specific. He is targeting a media landscape full of reboots, regurgitations, and re-visitation. Younger generations are constantly being dictated to. Hey, kids. You know what we liked? "Ghostbusters." Here's a brand new "Ghostbusters" that is 100% for us and not for you, but you better consume it anyway. We're recycling every idea and every visual cue, and we're exploiting the image of a dead actor. Enjoy!

Tom Six merely applied a revolting metaphor. An extreme political cartoon. Oh God, is "The Human Centipede 2" ... important?

And, just as "Star Wars" once came to influence actual American war activities — Ronald Reagan's fantastical spacebound Strategic Defense Initiative was nicknamed "Star Wars" — so too would "The Human Centipede" come to inform American institutions.

The most revolting of the series, "The Human Centipede 3 (Final Sequence)" pulled back another layer of reality, and saw Dieter Laser and Laurence R. Harvey playing prison wardens in a universe where the first two films are both but films. The characters in "(Final Sequence)" are monsters. They torture and mutilate the prisoners in their care, all under a waving star-spangled banner.

The Human Centipede as American policy

And some of the thing the Laser character eats ... Well, just consider this a dire warning against actually watching the film. Its tastelessness will be difficult to consume, even for the most jaded among us. "The Human Centipede 3" is, without exaggeration, one of the most nauseating films a human can experience.

In it, not only are the first two "Centipede" sequences films; director Tom Six also appears in the film as himself. To quell the rowdiness of a tortured prison population — at George H.W. Bush State Prison — Bill Boss (Laser) and Dwight Butler (Harvey) conceive the idea to make all the inmates into a massively long, hundred-person human centipede. The film details how many people would be required to make such an endeavor happen. A single psychopath cannot make a centipede of that size. Now, large groups of people must be convinced to participate. And, to do so, an argument must be made to its necessity.

No longer a media commentary, Six has — quite bluntly — taken aim at the grossness of the American prison system. The centipede can be seen as generations of unduly incarcerated American prisoners are force-fed American "ideals," all in the name of being reformed. The American criminal justice system, Six is saying, is an excuse for generational institutionalized madness to play itself out. The film ends with Bill Boss, shirtless and covered in blood, firing a gun into the air, wailing in insane glee as his hundred-person centipede languishes below.

The "Human Centipede" movies are too disgusting to enjoy, and any intellectual seeker will certainly be scared away by how aggressively contemptible they are. But Six, for all his adolescent shock impulses, had something to say.

It was gross, but he said it.