'Days Of Hate' And 'The New World' Use Comics To Explore America's Chaotic Future

It's a stacked week for Aleš Kot. The Czechoslovakia-born writer (now the Czech Repbulic), who you may know from his run on Marvel's Bucky Barnes: Winter Soldier, just had a six-issue Image trade paperback hit shelves this past Wednesday, July 18th. Days of Hate: Act One, created with artist Danijel Zezelj, captures a gloomy, divided, radicalized America in the immediate future. This coming Wednesday, July 25th Kot releases his next glimpse into America's oncoming transformation, also from Image Comics, the first issue of The New World with artists Tradd Moore and Heather Moore. It's set even further in the future, another dark entry that takes its cues from the current political malaise, but its vision of the United States is a whole lot topsy-turvier in comparison; a heightened world with a rotten core that exhibits itself proudly.

Both works stem from similar creative impulses — connecting the dots of the past and the present in ways they might someday manifest, especially for queer and/or non-white characters — though their varying takes on the Police State and misuse of power zero in on wildly different facets of the current zeitgeist. The former, Days of Hate, is about the mechanics of fascism as it exists in the shadows, creeping in on a society that has no choice but to either fall in line or respond in kind. The New World however, in which the protagonists' parents seem like they could be from our generation — a generation that failed them — features the all-out adsorption of fascism into popular culture, by a society that knows no other reality and must find new ways to fight it from within. And while they might sound like two contrasting takes, they function as sides to a coin.

Read on for our Days of Hate and The New World comic review.

Part One: The Writing on the Wall

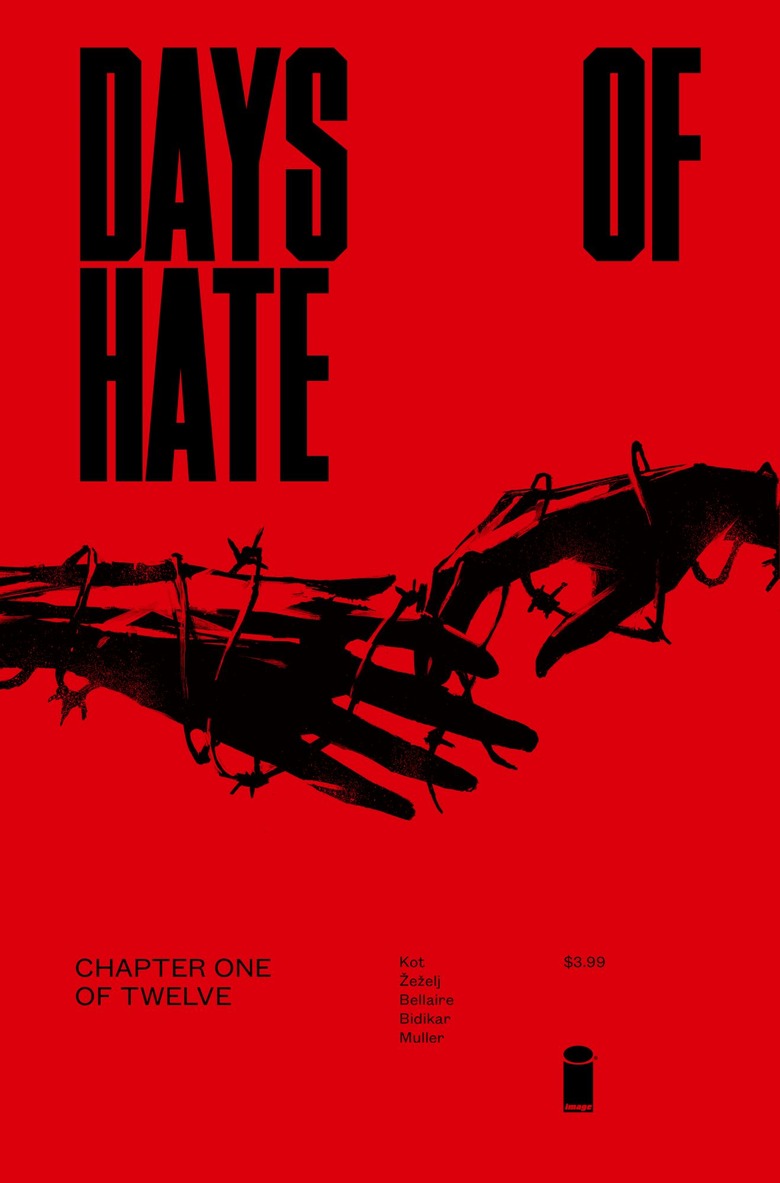

Days of Hate is a political love story that refuses to disguise itself. In an age where far too much dystopian fiction leaves its politics vague, the tale at hand is very much of the now. It first chapter, "America First," opens with a ragingly sexist and homophobic quote from former White House Chief Strategist Steve Bannon. Its very first panel is of a Nazi Swastika sprawled across a wall of a burned down gay nightclub. It speaks of work camps for dissenters, whose enforcers deny their very existence, and it paints a picture of events that may very well come to pass.

The book's cover, by Danijel Zezelj and Tom Muller, depicts hands attempting to reach out to one another, held back by barbed wire; a reflection of its twisted romance, steeped in bloodshed and moral ambiguity. When Huian Xing and her ex-wife Amanda have a tragic wedge driven between them, the former inadvertently lands in authority's lap, while the latter turns to radicalism to deliver swift and violent justice. Amanda and her accomplice Arvid, a Muslim man trying to protect his family, find themselves adrift and on the run, with a limited support network to aid their resistance. Xing on the other hand, must navigate the intimidation tactics of the state via Peter Freeman of the Special National Police Unit for Matters of Domestic Terrorism, whose crackdown against those who retaliate against White Supremacist terror, rather against than White Supremacist terror itself, speaks volumes.

Freeman, a personable family man, is portrayed with warm nuance in what feels like a narrative challenge. He's the only character in the who exhibits an overt sense of humour (circumstances certainly allow him to), though his attractive qualities stand shoulder to shoulder with the job he carries out, and the policies he represents. He is fascism come with a smile and open arms, a man "just doing his job" whose ugliness is subtle. Xing and Amanda on the other hand, are written into scenarios where they can't be personable, unless it's a front for survival some other purpose. They exhibit all the characteristics of duplicitous grey-hats, though by virtue of their very identities as queer women (and Xing's as a queer woman of colour), they are the defacto persecuted, whose instincts are driven towards survival and whose heroism feels innate, despite their ugliness towards one another.

Xing and Amanda's backstory unravels in unique fashion, at first in the form of dueling confessionals (Xing's to investigator Freeman, Amanda's to her accomplice), each with their own distinct point of view on the events of their relationship, before the narratives merge together in a dreamlike telling. Zezelj and colourist Jordie Bellaire create a world of darkness and shadow, where light seldom escapes even a metropolitan skyline — each page's black negative space is thick and visceral — though as the former couple's tale reaches its emotional zenith, colours and images overlap and bleed into one another, rife with narration from both points of view merging together, as if in exploration of dreams and memories, made fragile by political volatility.

Over the course of its first six issues, Days of Hate covers, by design, little ground in terms of plot (though it's certainly revving up to do so); Act One is the chessboard being set up, and how. Instead, it takes its time delving into its characters' psychologies, and the circumstances that birthed them. From the potential failures of 2018 and 2020, to the widening crevice of American bipartisanship and — informed by Kot's own formative years under and shortly after Soviet occupation — the mechanics, and acceptance, of authoritarianism.

[Read This if You Like: Munich, The Battle of Algiers, Army of Shadows, Hiroshima Mon Amour]

Part Two: A World Gone Mad

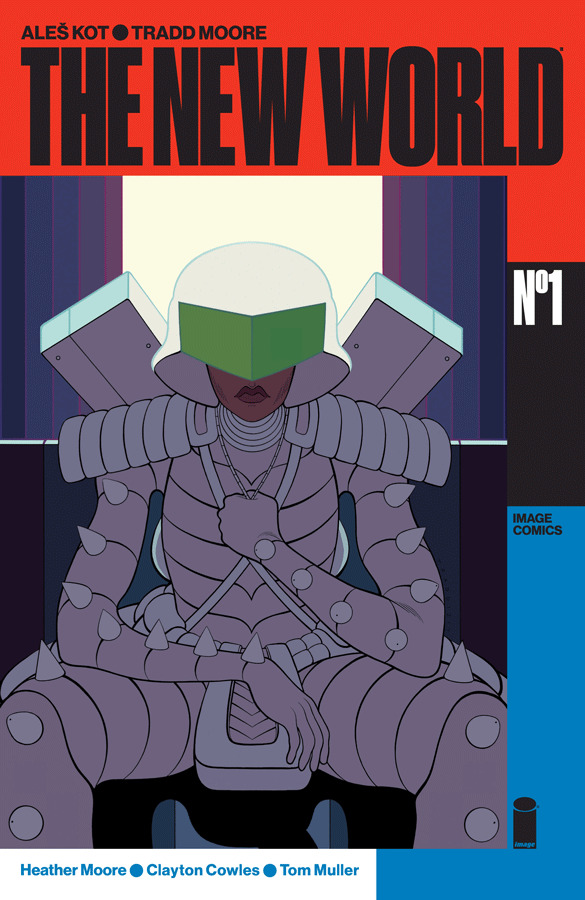

Where Days of Hate keeps its characters divided and isolated, The New World drops us headfirst into a vibrant, packed society dripping with colour; a pop-art retro-future to contrast the darkness of 2022. The book's L.A. locales are born of a cross-section of cultures, with "The New California" bordering a vast American wasteland as a result of a Second Civil War. One of its protagonists, Kirby Miyazaki, is a bisexual Japanese-American anarchist and a straight-edge vegan, an identity his easy-going millennial father wears like a badge of honour. The other is a Black/biracial television star from a political family, whose nightlife involves the embrace of her African roots as she dons tribal markings before hitting the club. It is, on the surface, a borderline satirical liberal wet-dream, though it incisively holds accountable the idea — one with the potential to be propagated on either side of the political aisle — that "This is the future that liberals want," a future in which politics only have the appearance of harmony and acceptance of diversity, but one whose class-centric policies tell a different story. In The New World, society is still very much divided along economic lines, though its most terrifying facet is perhaps this future America's biggest unifier: a widely-watched reality show where cops hunt down impoverished criminals, and viewers get to vote on whether suspects live or die.

See, the television star in question, Stella Maris, is both the granddaughter of the iron-fisted President, and a cop who partakes in this fascist rigmarole. She often goes against the will of the people (her conscience forces her to spare the criminals despite the public demanding otherwise), though she still actively serves an arm of the State. Kirby, on the other hand, when not performativity announcing some facet of his lifestyle ("Do you want a drink? // "Nah, thanks. I'm straight-edge!"), still puts in the groundwork to disrupt the system, hacking in to the State's broadcast to denounce its monetized police violence.

Despite its first mega-issue being filled to the absolute brim with potent ideas, The New World also has the time to introduce a gloriously attractive conceit: what if Stella and Kirby, unaware of each other's role in this State-sanctioned death game, become romantically involved under the watchful eye of Big Brother?

Tradd Moore and Heather Moore blend the worlds of utopia and dystopia with gusto, giving their cops a Mad Max-inspired vigilante-superhero aesthetic (the head of the broadcast is even reminiscent of director George Miller) while draping Kirby in all-American biker gear that calls to mind unapologetic masculine aggression, with a scar and eye-patch to boot. Stella and her authoritarian ilk are the perpetrators of this post-apocalyptic wasteland rather than its victims (a moral desert more than a literal one), while Kirby employs distinctly non-violent tactics. In subverting these expectations of iconography, the creators are able to zero in on our perceptions of violence and when we consider it acceptable; with COPS pushed to its logical extreme on one hand, in a controlled, documented environment where bloodshed is the expected outcome, and activism that wears the face of chaotic anarcho-terrorism on the other, minus an actual body count.

The New World's future is certainly fun — its friendly technology, its zany pets, its trippy social gatherings —but it's a future where people live ostensibly normal lives for the most part, despite the ubiquitousness of authoritarianism. It's when authority comes a-knocking, often in the form of sudden overreaches of power, that things start to feel dire; as if the daily return to normalcy despite decrying current leadership is the ultimate signifier of banal evil. It's a world gone mad, but it's not far off from ours.

[Read This if You Like: Romeo and Juliet, The Purge series, Mad Max: Fury Road, The Hunger Games]

Part Three: A Supplemental Ghost Story

Aaron Stewart-Ahn, co-writer of upcoming Nicholas Cage film Mandy, along with Indian artist Sunando C. also lend their talents to The New World, albeit in an unrelated post-script. The quiet short story Work Nights, the first in a series of occult tales in the modern world, isn't connected to the events of Kirby and Stella's narrative, though it feels like part and parcel of their futuristic tale, one steeped in the violence of media. The future, and the present, are always influenced by the ghosts of the past. In The New World, the ghosts are the mistakes we let run amok in the 2010s. In Work Nights, the ghosts are more mysterious, more ethereal and more tethered to history, yet somehow, just as immediate.

In a Hollywood hotel, a Korean-American front desk clerk continually investigates the complaints of her celebrity guests. Rumours abound about the nature of the spectre present in Room 708, one that speaks to actors and musicians of all varieties through an old television. That is, the television itself and the programs beamed to it do all the talking, displaying stark, disturbing images that intrude on its guests, though images that feel pulled from real programming and our every day.

Some guests attempt to block out these garish images. Some, like history's great artists, take inspiration from these violent ghosts, embracing the imagery and remixing it. Others, like the desk clerk, find sorrow in reflections of family. In a world inundated with information, beamed to us always from the decades, weeks or seconds ago (but never in the present), we ourselves begin to live in a perpetual past, where ghosts become entangled with our very consciousness.

Days of Hate: Act One is available now. The New World #1 arrives this Wednesday.