'Spider-Man: Into The Spider-Verse' Is A Superhero Movie About The Power Of Art

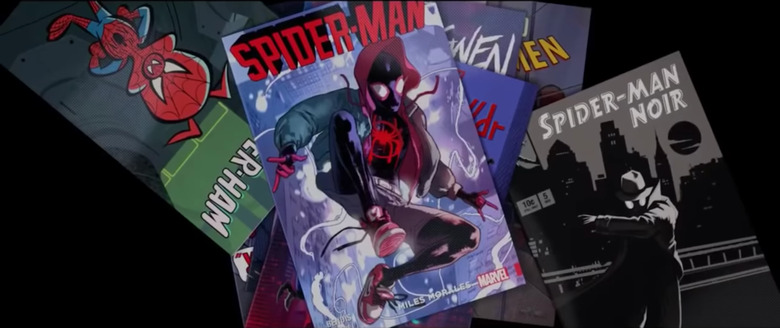

Miles Morales is an artist.We're introduced to the movie version of Miles (Shameik Moore) as he sits at a drawing table sketching a sword-wielding robot. On his way to school, he slaps custom sticker tags on street signs where he hopes his father, a police officer, won't find them. When he wants to express the vastness of the shoes he has to fill — the "great expectations" of his elite schooling academy — he ventures underground with his uncle Aaron (Mahershala Ali) and creates ornate graffiti murals. His bedrooms, both at home and at school, are littered with an assortment of creative works, from a Chance the Rapper Coloring Book poster to piles of Spider-Man comics.Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse is the world through Miles' eyes, and it does tremendous justice to the story of creativity at its core. The expectations Miles fall short of soon shift from academia to super-heroics; the film follows suit. In nearly every scene, it layers comic-inspired motion and paneling to tell its story, not only paying stylistic homage to the source material, but framing Miles' thoughts, feelings and even movements as he navigates coming-of-age.

Capturing Momentum

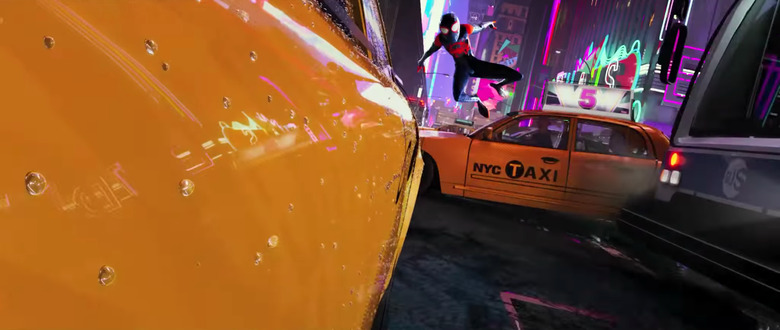

Action-lines are used to approximate motion in comics. The trick works in all directions across a two-dimensional plane, but it's especially effective when the movement is towards (or away from) the reader. It often becomes a matter of point-perspective — a technique commonly associated with the Renaissance, though its origins go back further — but rather than mathematical precision, the comic version skews geography, as if to move the reader along with the heroes. It's a snapshot of motion in a static medium, though when the effect is translated to a moving picture, the result is kinetic.Point perspective is common in cinema too, mastered by the likes of Kubrick, but Into the Spider-Verse employs the technique in a manner that blends both art forms. While present in the film's imagery throughout, it's especially potent during key moments when Miles swings into action.

The lines that frame this perspective are sometimes themselves in motion. Whether beams from Wilson Fisk's supercollider, or simply New York's trains and taxis, the living environment enhances Miles' motion either by moving in the same direction as him — allowing him to overtake the lines in question — or by moving in the opposite direction and enhancing the exaggeration.

The lines that frame this perspective are sometimes themselves in motion. Whether beams from Wilson Fisk's supercollider, or simply New York's trains and taxis, the living environment enhances Miles' motion either by moving in the same direction as him — allowing him to overtake the lines in question — or by moving in the opposite direction and enhancing the exaggeration.

The action lines even apply to the characters themselves, re-creating the effects of the comics. Some, in the vein of ink-line smears in hand-drawn animation, approximate rapid movement:

The action lines even apply to the characters themselves, re-creating the effects of the comics. Some, in the vein of ink-line smears in hand-drawn animation, approximate rapid movement: Others approximate impact, imitating sharp sounds on the page:

Others approximate impact, imitating sharp sounds on the page: Some approximate the feel of anaglyph 3D — the good old red-and-blue:

Some approximate the feel of anaglyph 3D — the good old red-and-blue: And some moments of impact are even punctuated by comic-appropriate onomatopoeia:

And some moments of impact are even punctuated by comic-appropriate onomatopoeia:

Occasionally, the lines aren't used to punctuate movement at all. The introduction on Peni Parker (Kimiko Glenn), for instance, echoes the stylizations of Japanese anime and manga, as if light itself is being bent around her:

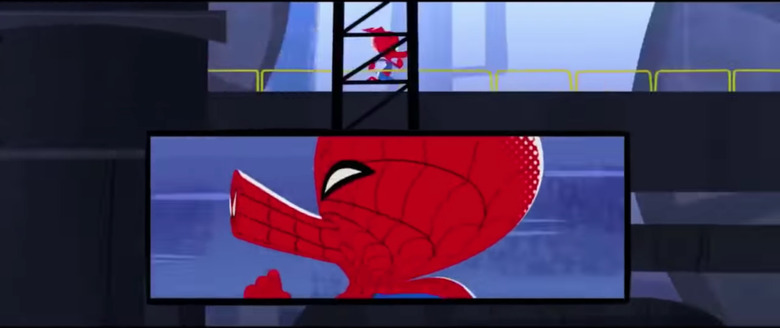

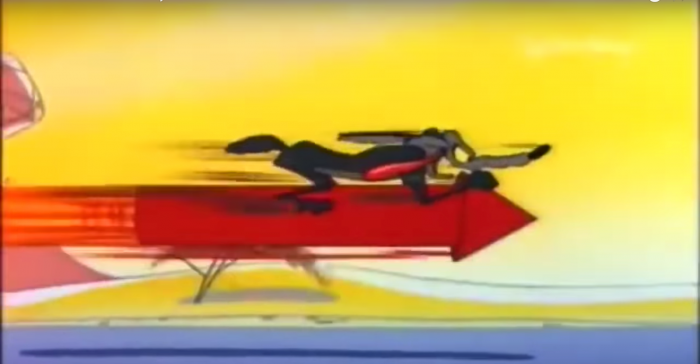

Occasionally, the lines aren't used to punctuate movement at all. The introduction on Peni Parker (Kimiko Glenn), for instance, echoes the stylizations of Japanese anime and manga, as if light itself is being bent around her: Peni's movements, along with those of Spider-Ham's (John Mulaney), are emblematic of the exaggerated styles to which they pay homage. The hyper-expressiveness of anime, and the hyperactivity of old Warner Bros. toons, are each blended seamlessly into a world of more "realistic" motion:

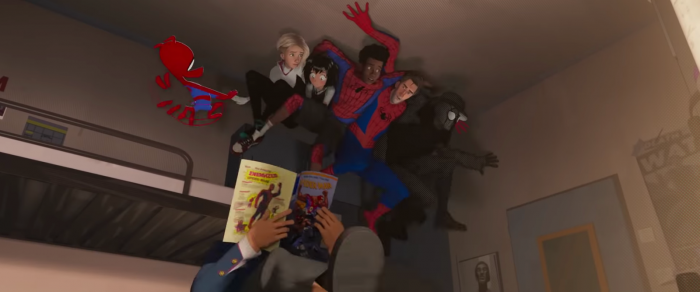

Peni's movements, along with those of Spider-Ham's (John Mulaney), are emblematic of the exaggerated styles to which they pay homage. The hyper-expressiveness of anime, and the hyperactivity of old Warner Bros. toons, are each blended seamlessly into a world of more "realistic" motion:

Also worth noting: Spider-Man Noir (Nicolas Cage) on the far right, posed like an old Sandman comic from the 1930s. He's even textured as such.

Also worth noting: Spider-Man Noir (Nicolas Cage) on the far right, posed like an old Sandman comic from the 1930s. He's even textured as such.

Form as Point-of-View

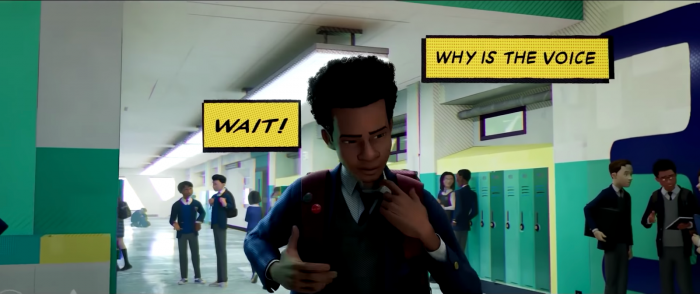

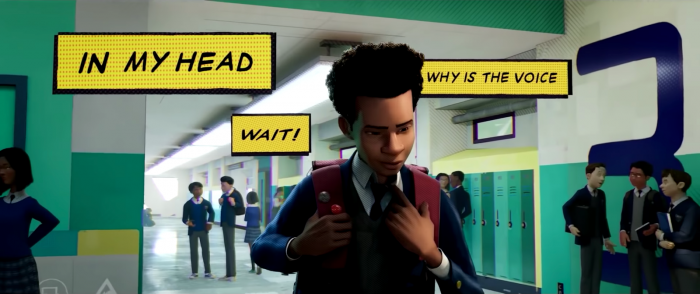

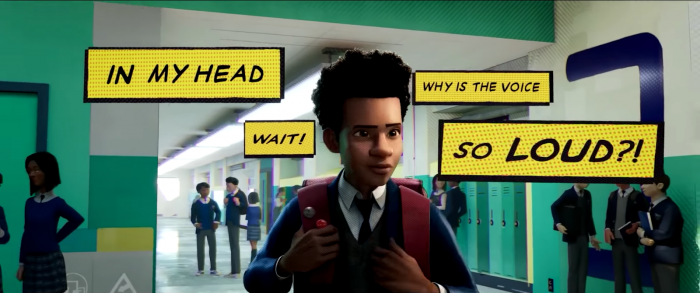

The comic flourishes don't just exist to remind viewers of the source. When Miles first deals with getting his powers, his invasive, paranoid thoughts begin to manifest as comic book paneling. As he moves through physical space, the narration boxes shift into the background — another great use of 3D — and they're replaced by new ones that are equally impactful:

Transposing these elements to film ends up uniquely transformative. Motion allows the narrations to forego a traditional left-to-right, the western orientation of the page. We don't need to see the boxes in a familiar pattern, since we track the order in which they first appear and read them accordingly. The final image, when read as a singular panel, is chaos — "IN MY HEAD why is the voice Wait! So LOUD?!" — not unlike Miles' state of mind at this point.Another example of this effect is Miles moving through his school hallway after an embarrassing encounter with Gwen (Hailee Steinfeld). Rather than narration boxes however, his thoughts are invaded by overlapping panels that exaggerate background details; bits of information of which he's now hyper-aware thanks to his Spider-sense. A clip of this scene isn't available online, but to illustrate, the effect also shows up during the film's backstory recaps:

Transposing these elements to film ends up uniquely transformative. Motion allows the narrations to forego a traditional left-to-right, the western orientation of the page. We don't need to see the boxes in a familiar pattern, since we track the order in which they first appear and read them accordingly. The final image, when read as a singular panel, is chaos — "IN MY HEAD why is the voice Wait! So LOUD?!" — not unlike Miles' state of mind at this point.Another example of this effect is Miles moving through his school hallway after an embarrassing encounter with Gwen (Hailee Steinfeld). Rather than narration boxes however, his thoughts are invaded by overlapping panels that exaggerate background details; bits of information of which he's now hyper-aware thanks to his Spider-sense. A clip of this scene isn't available online, but to illustrate, the effect also shows up during the film's backstory recaps:

Origin Stories

The characters' quick-fire origin tales are often told through inter-locking comic panels, some even framed by webs. This allows for multiple stories to be illustrated in quick succession, while also painting a portrait of a full life of Spider-hood that we haven't seen: Not only are these montages a fun visual shorthand — Peter (Jake Johnson) stomps on a glass at his wedding; he's finally Jewish in the text! — but the presence of these origins for each new player helps establish them as experienced Spider-people. Not just through action, mind you, but through the loss they inevitably experience. As even casual fans know, given the character's omnipresence in popular culture, a death on one's conscience is an inescapable part of Spider-Man's mythos.Minor spoilers to follow.Miles, unlike the other heroes, is just starting out — both as a crime fighter, and as someone with lots to lose. Spider-people from various dimensions comfort him after the death of a loved one, and of course, his subsequent guilt. Even if we don't see every death they reference, mere hints of Peter Parker's Uncle Ben, Peter B. Parker's Aunt May and Spider-Gwen's best friend are enough to make the weight of Peni's, Spider-Man Noir's and even Spider-Ham's respective losses feel tangible.One of the film's most affecting moments is so ridiculous on paper — an anthropomorphic, Looney Tunes-inspired pig voiced by a stand-up comedian joins in the collective mourning — but it expresses, with devastating clarity, the idea that mortality and death are inescapable facets of even the most escapist fantasy."You can't save 'em all."The divergent animation styles serve to punctuate this coming-together, as if the notions of heroism, guilt and loss connect them beyond universe and style and genre — the very webs that frame each origin stale also appear to physically connect their universes when the dimensions open up. As the Spider-folk commiserate, telling Miles they're probably "the only ones who do understand," the emotional heft feels earned.We've seen flashes of the lives they've lived, and we've likely seen a full version of this story on screen at least once. Given the film's multiversal concept, their tales are variations on a theme that's now culturally ingrained — a story perfected by Sam Raimi fourteen and sixteen years ago with the first two Spider-Man films.In contrast to our heroes' collective mourning, however, the villain Wilson Fisk (Liev Schreiber) lacks the same mechanics and support system to deal with loss. This also happens to be the very impetus for his dimension-hopping scheme. His grief is so unmitigated and so un-confronted, forever trapping him in the bargaining phase, that it endangers the entire world. The result of his experiments is a kaleidoscopic mish-mash of crumbling buildings, as if giving physical form to Fisk's erratic emotional architecture; an ugly embodiment of using great power irresponsibly.

Not only are these montages a fun visual shorthand — Peter (Jake Johnson) stomps on a glass at his wedding; he's finally Jewish in the text! — but the presence of these origins for each new player helps establish them as experienced Spider-people. Not just through action, mind you, but through the loss they inevitably experience. As even casual fans know, given the character's omnipresence in popular culture, a death on one's conscience is an inescapable part of Spider-Man's mythos.Minor spoilers to follow.Miles, unlike the other heroes, is just starting out — both as a crime fighter, and as someone with lots to lose. Spider-people from various dimensions comfort him after the death of a loved one, and of course, his subsequent guilt. Even if we don't see every death they reference, mere hints of Peter Parker's Uncle Ben, Peter B. Parker's Aunt May and Spider-Gwen's best friend are enough to make the weight of Peni's, Spider-Man Noir's and even Spider-Ham's respective losses feel tangible.One of the film's most affecting moments is so ridiculous on paper — an anthropomorphic, Looney Tunes-inspired pig voiced by a stand-up comedian joins in the collective mourning — but it expresses, with devastating clarity, the idea that mortality and death are inescapable facets of even the most escapist fantasy."You can't save 'em all."The divergent animation styles serve to punctuate this coming-together, as if the notions of heroism, guilt and loss connect them beyond universe and style and genre — the very webs that frame each origin stale also appear to physically connect their universes when the dimensions open up. As the Spider-folk commiserate, telling Miles they're probably "the only ones who do understand," the emotional heft feels earned.We've seen flashes of the lives they've lived, and we've likely seen a full version of this story on screen at least once. Given the film's multiversal concept, their tales are variations on a theme that's now culturally ingrained — a story perfected by Sam Raimi fourteen and sixteen years ago with the first two Spider-Man films.In contrast to our heroes' collective mourning, however, the villain Wilson Fisk (Liev Schreiber) lacks the same mechanics and support system to deal with loss. This also happens to be the very impetus for his dimension-hopping scheme. His grief is so unmitigated and so un-confronted, forever trapping him in the bargaining phase, that it endangers the entire world. The result of his experiments is a kaleidoscopic mish-mash of crumbling buildings, as if giving physical form to Fisk's erratic emotional architecture; an ugly embodiment of using great power irresponsibly.

Unique Framing

Eventually, once Miles rises to the occasion, his coming-into-Spider-hood is punctuated by him finally getting his own comic. The moment he arrives, all decked out in a sure-to-be-iconic look, the film even tweaks the way it presents him.For the majority of the runtime, our heroes are brought to life in the vein of traditional cel animation, in which frames of characters were often repeated. For instance, two identical character frames for every one frame of moving backdrop:

In technical terms, it's animating movement "on two's."This effect is re-created in Spider-Verse whenever Miles moves through space. The technique isn't usually employed by CG animation, so its presence helps grant the film a unique visual aesthetic:

In technical terms, it's animating movement "on two's."This effect is re-created in Spider-Verse whenever Miles moves through space. The technique isn't usually employed by CG animation, so its presence helps grant the film a unique visual aesthetic:

[If you'd like to test this yourself, the "." and "," buttons help navigate YouTube videos frame-by-frame. Try it!]Occasionally, even as other Spider-characters move a frame at a time, Miles' frames still double up — like he's lagging behind the more seasoned heroes.

[If you'd like to test this yourself, the "." and "," buttons help navigate YouTube videos frame-by-frame. Try it!]Occasionally, even as other Spider-characters move a frame at a time, Miles' frames still double up — like he's lagging behind the more seasoned heroes. However, once when Miles finally takes his leap and harnesses his powers, the film presents him in slow-motion, which necessitates smoother movement. Both Miles and his surroundings begin progress at the same speed, and even when he isn't slowed down (for instance, his free-fall), his movement is more harmonious, more in tune with the surrounding animation.He feels like he belongs.

However, once when Miles finally takes his leap and harnesses his powers, the film presents him in slow-motion, which necessitates smoother movement. Both Miles and his surroundings begin progress at the same speed, and even when he isn't slowed down (for instance, his free-fall), his movement is more harmonious, more in tune with the surrounding animation.He feels like he belongs.

Miles Morales, Spider-Man

What's especially notable about Miles' big "arrival" is the form his costume takes. The comic version of Miles — more interesting in concept than execution — has always felt lacking in this department. He gets his red-and-black suit readymade from Nick Fury, rendering it just another standard outfit. In Spider-Verse however, Miles spray-paints over the existing Spider-Man design and makes it his own — as if in tribute to his uncle, and the creativity they shared.It's the perfect expression of Miles' artistic spark coming to fruition, not to mention the perfect dramatization of the idea at the film's core: that "Spider-Man" is about what each unique individual brings to the table. Each Spider-person in the film has their own set of skills; Miles' talent is expressing himself visually through paint, and his costume being a unique artistic creation speaks volumes about his arc.Miles' most important moment isn't that he decides to take action — he's enthusiastic to help the other Spider-folk from the get-go — but rather, that he's finally able to do so. His turning point comes not through answering a call to action or through finding some hidden bravery, but rather, through his father Jefferson (Brian Tyree Henry) finally expressing his belief in his son.Miles not only has to overcome lofty expectation, but his father's disdain for Spider-Man. The young hero arrives at this emotional point shortly after being told by the other Spider-people that he isn't up to the task. Peter reminds him being ready would require a leap of faith — a lesson he reflects back to Peter to quell his fears about failure — but Miles isn't ready to take his leap until his father stands outside his bedroom door. Jefferson, who often struggles to connect with his son, uses the language of an out-of-touch parent trying desperately to nurture creative talent:"I see this spark in you. It's amazing."Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse is a story about art, taking shape as an ode to the very art forms that birthed it. It's a Spider-Man movie that pays homage to other Spider-Man movies, a Spider-Man cartoon that incorporates elements from Spider-Man cartoons, and a moving, breathing Spider-Man comic that brings to life — in composition, texture and most importantly, theme — the very pages that have made Spider-Man so enduring.Ultimately, it's a story of why Spider-Man, in concept, will continue to endure, circling all the way back around to Stan Lee and Steve Ditko's original idea. That anyone can wear the mask, and anyone can be a hero.