Exploring The "Cinematic Unrealism" Of Rian Johnson And Why It Works So Well

"I just didn't think it was realistic enough."How often have you heard someone's complaints about a movie essentially boil down to this talking point? If you've spent enough time on Twitter, Facebook, YouTube comment sections, you've heard it. No matter the forum, film-related discourse in the 21st Century undeniably tends to fall back onto realism. Not that this is problematic in and of itself, but look no further than the cottage industry of popular "satirical" video channels that have gained massive followings in the past decade or so and focus exclusively on lazily snarking on factual inaccuracies and "unrealistic" plot elements to see just how easily this mode of thinking can go awry.But what is realism, anyway? And what does director Rian Johnson have to do with this conversation? This might seem like a dumb question, but any proper discussion of film and filmmaking styles must first acknowledge the historical context. Let's define our terms."Realism" and "formalism" are two such styles that date back to the very creation of moving pictures as an art form. First popularized in the mid-1940s, French film theorist Andre Bazin spearheaded the argument that realism ought to be the purest function of cinema, by which the combination of certain camera techniques, editing styles, and shot compositions must be used for very specific purposes – namely, in removing all traces of "manipulation" on the part of the director, depicting everyday life exactly as it is, and ostensibly capturing the "objective truth" of human existence through a nearly documentary-like lens. Meanwhile, formalism exists on the opposite end of the spectrum, leveraging abstraction and expressionism to throw realism out the window in direct juxtaposition with our far less fanciful reality (this Patrick Willems video essay provides a solid overview of both film theories).It's arguable, in fact, that we're currently witnessing the pendulum swing back to filmmakers and audiences alike craving realism in film after decades of formalist art, such as lavish musicals and fantastical blockbusters, dominated pop culture. Consider Christopher Nolan's steadfast championing of the IMAX format and his commitment to grounded elements in his films. Peter Jackson made waves with his impressive, yet controversial effort to colorize and recreate sound effects along with dialogue from silent WWI footage recovered for his documentary They Shall Not Grow Old. Most recently, Ang Lee's audacious but hit-or-miss attempt at packaging 3D, 4K resolution, and High Frame Rate together for the most immersive experience possible was on full display with Gemini Man. And if the over-performance of Todd Phillips' Joker is any indication, even comic book movies are profiting from resisting their fantasy aspirations. It would seem that many of the biggest films and most distinctive artists are leading the charge in a very specific brand of filmmaking – one that relies heavily on cinematic realism.And then, as promised, there's Rian Johnson.Some of the most compelling filmmakers working today infuse their art with certain styles, themes, and concerns – ones that they can't help but return to over and over again. In Johnson's case, his most enduring preoccupation closely resembles what I call "cinematic unrealism". This particular style highlights the way that the purposeful heightening and bending of real-world logic in an otherwise familiar setting can have a profound effect on storytelling... in a way that abject realism, formalism, or even the middle ground of classicism could never accomplish.Alone, this idea of cinematic unrealism hardly scratches the surface of who Rian Johnson is as a living, breathing, constantly evolving artist. But perhaps this particular window into his work can lend insight to a singular talent who, given the overwhelmingly positive response to Knives Out, is currently operating at the peak of his abilities.

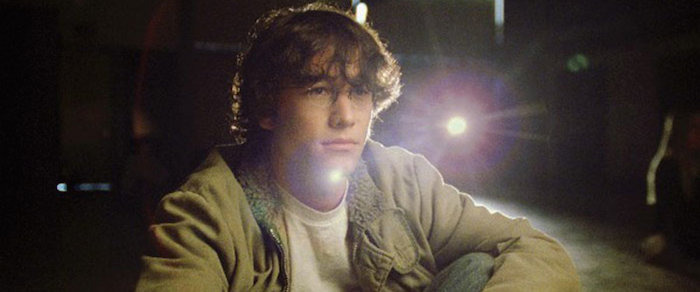

Brick

Suspension of disbelief.Chances are regular readers of this site are familiar with that ever-fluid concept, the invisible line of boundary-pushing a viewer can reasonably accept based on the world-building and "rules" a film establishes for itself. For some, the line in the sand that shatters immersiveness and prevents engagement can amount to something as arbitrary as the visual medium of animation (anyone with elderly family members can likely attest to this). For others, all it takes to invest in a story is for a film to commit to a certain level of disbelief and then never deviate.Naturally, Brick wastes no time in announcing precisely the amount of suspension of disbelief it requires from audiences.From crime lords to femme fatales to moody lighting drenched in harsh shadows, Rian Johnson's 2005 feature debut follows all the tenets of a standard neo-noir murder-mystery... with a twist: nearly all the action revolves around teens in a contemporary high school setting. So rather than, say, Ryan Gosling and Harrison Ford trading self-serious barbs in a conspiratorial plot of profound implications like Blade Runner 2049, we have a teenage-passing Joseph Gordon-Levitt delivering hard-boiled dialogue with a snappy cadence and gleefully dated colloquialisms to pulpy archetypes with names like Brain and Tug and Pin, all of which should be impossible to buy into.Oh, and that dialogue? Referring to such intoxicating speech as "heightened" almost does it a disservice – this is the snappy, dryly humorous type that almost goes by too fast to even catch, the kind that conveys personality every bit as much as it does exposition. Yet it's delivered naturally enough that we could be fooled into feeling capable of coming up with such witticisms ourselves on the spot, though on some level we know it would sound unbearably pretentious if we tried.Some viewers never quite manage to reconcile the idea of "But kids don't talk like that!" with the lofty ambitions Johnson is aiming for. Those able to get past that obstacle, however, are treated to a wonderfully idiosyncratic genre mashup that functions as an adoring throwback to classic noir just as much as a coming-of-age tale of an emotionally repressed teen coming to grips with lost love.What makes all this so effective, of course, is Johnson's near expert knowledge of film history and the basics of storytelling. Despite such a cobbled-together budget, stylized shots and camera placements either harken back to past inspirations or further invest us in the story. Each second of careful editing doles out crucial information while withholding others, both of which contain several layers of meaning. Every instance of blocking seemingly enhances Brendan's (Gordon-Levitt) loneliness by repeatedly swallowing him up in wide shots of the surrounding landscape, or hints at the power imbalances in the many uneasy alliances he must forge.But it's in the writing, from dropping these characters into such a setting in the first place to that language of "noir-ese", where Johnson's penchant for unrealism plants its flag and refuses to fade into the background. It's there all throughout Brendan's outsized journey as it turns from a quest to win back his jilted lover Emily (Emilie de Ravin) to a guilt-ridden attempt at atonement in identifying her killer(s). You can see it in every one of Brendan's charged interactions with ex-girlfriend Kara (Meagan Good) and tough guy Dode (Noah Segan), trying to suss out clues from a pair who are clearly keeping secrets. And it's most evident in the film's femme fatale Laura (Nora Zehetner), a beautiful cipher that Johnson made sure was given the dignity of her own agendas and goals.For me, a tête-à-tête between Brendan and the local drug kingpin (Lukas Haas, appropriately referred to as The Pin) sums up why there's so much to love here. As the unlikely pair takes in a particularly striking sunset on the beach, The Pin suddenly brings up JRR Tolkien and his descriptive writing; the sort of prose that, in his own succinct words, "makes you want to be there." Rian Johnson seemingly took that to heart by crafting exactly the sort of movie that makes you want to be there and yearn to live in it, even if only for a moment.Brick is a story of tragic romances, untimely deaths, operatic drama, moody atmosphere, and sullen, broody loner teens; all filling in their genre niches and all played refreshingly straight without a wink of irony or unease, to surprisingly humorous and heartfelt results. But more than that, it's a gauntlet thrown down in support of suspending our disbelief when it leads to an infinitely more rewarding experience. It's an unflinching display of cinematic unreality in motion – one that acts as a key to unlocking the rest of Johnson's movies.

The Brothers Bloom

Barely three years after his debut and not content to repeat the same trick twice, Rian Johnson's second feature sees him dabbling in a genre where unrealism is the main goal – a story explicitly about con artists and their complicated relationship with truth, with reality itself.Initially, the first 6 or 7 minutes of The Brothers Bloom seem to be a mere continuation from where Brick left off: in a rapid-fire montage, we're introduced to Mark Ruffalo's Stephen and Adrien Brody's Bloom as a burgeoning team of talented, orphaned grifters at the tender ages of thirteen and ten, respectively. Stephen is the writer and architect of their elaborate schemes while Bloom is the performer, dutifully acting out the roles he's been given as an escape from his insecurities. If the late actor/magician Ricky Jay's rhyming storybook narration doesn't give it away, the brothers' matching outfits (black suit jackets and top hats – you know, normal children's fashion!) and larger-than-life mannerisms immediately clue us into the tone of the film.Looking for realism? You've once again come to the wrong place.By the time the script jumps ahead 25 years, the dramatic conflict at the heart of The Brothers Bloom becomes clear. Haunted by the childhood memory of their con getting in the way of innocence and romance, Bloom has become a con man sick and tired of living vicariously through his brother's stories, threatening – not for the first time – to break up the duo for an early retirement and desperate to live in the real world with his own experiences for a change. As Bloom struggles to articulate his wants and needs, Stephen ironically finishes the thought for his frustrated brother, "You want an unwritten life."That this attempted parting of ways doesn't last for very long isn't very surprising. What is surprising, however, is the target of Stephen's final con, Penelope Stamp (an impeccably cast Rachel Weisz). A wealthy shut-in who's rarely ever left home and passes the time "collecting hobbies", Penelope has spent a lifetime observing others from a distance and teaching herself an endless variety of random skills. It's this lonely and sheltered and book-learned existence that, on some level at least, drives Stephen to choose her as their "mark" to give her a taste of adventure with Bloom – artificial and duplicitous though it might be.Once Bloom reluctantly accepts this latest con and hits it off with out-of-practice conversationalist Penelope after their "chance encounter", an intimate dinner conversation about her childhood reveals why she serves as his perfect foil.After an entire childhood quarantined due to a mistaken allergy diagnosis and then an adolescence spent indoors caring for her ailing widowed mother, Bloom gently inquires whether she feels cheated out of a normal life. As only a storyteller who loves to tell stories could put it, Penelope's ensuing monologue – beautifully performed by Weisz and impeccably written by Johnson, it bears noting – sums up everything we need to know about this character who, in the wrong hands, could've amounted to little more than a series of quirky affectations. Rather than letting uncontrollable events dictate her reactions, Penelope explains how she chose to dictate her feelings through stories she told herself; ones about finding the ability to love her mother and not resent her, about making her circumstances a little less miserable, about finding "infinite beauty" in everything.As Bloom eventually learns, con stories are inherently distortions of reality, mere fantasies that we tell ourselves and others to provide our own wants and needs. Penelope uses similar stories as both escape and self-deception. "The trick to not feeling cheated is to learn how to cheat," as she puts it. A woman who's always used stories to escape reality and create her own, paired with a conflicted con man seeking to escape his brother's invented narratives in order to create his own – is it any wonder these two broken individuals were placed at the center of a con man story wrapped in a romance?This delicate interweaving of themes is why Bloom and Penelope's love story hits as hard as it does, especially by the end when Bloom reaches for her outstretched hand and rides into the sunset with her "...like we're telling the best story in the whole world". Johnson managed to craft all this within the larger overarching idea of how unrealism can be more than just a twist on film theory. On top of entertaining us, the best stories have something meaningful to say about our experiences and The Brothers Bloom uses character, unabashedly romantic overtures, and the unrealism of a con film to do exactly that.

Looper

If Brick threw us headfirst into unrealism by deftly uniting such disparate tones and The Brothers Bloom approached it meta-textually through the beloved genre of con stories, then Looper is where Rian Johnson built unrealism right into its very premise.Hardcore realists and logic-obsessives, look away now!The year is 2044, and it'll be another thirty before time travel is invented in the world of Looper. The outlawed practice will eventually have fallen into the hands of shady crime syndicates and exclusively used to send targets thirty years into the past where loopers, such as Joseph Gordon-Levitt's Joe, promptly execute them and dispose of their bodies.After Joe fails to "close his loop" when confronted with killing his own future self (Bruce Willis), a frantic effort to protect his unfulfilled way of life while dodging his ruthless handlers soon turns into something altogether more complicated. Ominous warnings of an unhinged crime boss in the future known as the Rainmaker, Future Joe's disturbing knowledge of the Rainmaker's existence as a child in the present, and Present Joe's encounter with a loving mother (Emily Blunt) and her suspicious child all add up to a tense exercise in inevitable conflict. The realization that this serves as a neat twist on the "baby Hitler" thought experiment is only the cherry on top.So naturally, a significant amount of the post-release discourse ended up revolving around one thing: the fact that none of this makes much logical sense.Why wouldn't these future criminal organizations use their time travel machine to transport their unfortunate victims, say, to the bottom of the ocean or inside an active volcano? Why not kill them before sending them back through time? Why force loopers to kill their own future selves in the first place rather than tasking literally any other hitman to do it? In effect, why pick the least efficient method with the most points of failure as their standard operating procedure?Allow me to answer these concerns with a single line of dialogue courtesy of Future Joe himself: "It doesn't matter!"Depicting time travel can be a messy business - just ask virtually anyone involved with Avengers: Endgame. But true to form, Rian Johnson finds a simple yet ingenious way around such distractions: he turns the subtext into text by speaking directly to us. During a pivotal scene, the two Joes meet for a terse conversation to clear the air. Knowing just how tempting it is to fall down the rabbit hole of time travel logistics, Future Joe angrily drives the point home to Present Joe – and, by extension, us – to stop obsessing over the meaningless logic of it all and focus on what's important instead.Again, "It doesn't matter!"Of course, such brazen ambiguity won't satisfy everyone – especially among the CinemaSins crowd, where so-called "plot holes" and characters that dare to be flawed or act irrationally are perceived as unmitigated failures of storytelling, rather than intentional choices that make for interesting human narratives. But this is where Johnson emphatically makes his case, urging viewers to forgo realism and real-world logic in favor of getting lost in a fantastical metaphor that would only be possible through this leaky yet dramatically compelling premise.What's being advocated for here isn't a "Turn your brain off and go with it" mindset, to be clear, but a "Don't miss the forest for the trees" approach that prioritizes emotional resonance over rote plot mechanics. After all, only the most humorless literalists would throw out a convoluted setup rather than mine such an imaginative idea for as much purely sci-fi imagery as it's worth.Looper is a slight departure from Johnson's previous work in that, despite the outwardly sci-fi trappings, it's perhaps his most grounded film to this point. But as with his entire oeuvre, he clearly understands the main purpose of genre; in this case, to use impossible concepts and high-minded ideals as a simple allegory for our present.How else would one conjure up a scenario where a man with a tortured past and who's lost his grip on the present could be forced to confront his own future self? What better way to humanize a bitterly broken old man consumed by rage and grief than to pit him against the literal embodiment of his past regrets and mistakes? And at its heart, does a marginally unwieldy premise really negate the poignancy to be found in a mother trying to redeem herself by raising her frightened, volatile son – an innocent child who unknowingly holds the power to either continue endless cycles of pain and death... or to break it?None of this, however, would resonate without an audience willing to engage with a film on its own terms in order to find the many insights underneath. And if that's not the core essence of unrealism, I don't know what is.

Star Wars: The Last Jedi

Serving as much of the world's first introduction to his distinctive sensibilities, Rian Johnson's unexpected foray into the world of Star Wars with The Last Jedi provides a fascinating opportunity to observe an independent filmmaker's proclivities filtered through a massive blockbuster built for mass appeal. Fans can appreciate how he found a way to seamlessly insert himself into an ongoing franchise (a trick learned, no doubt, from his experience directing multiple episodes of Breaking Bad well into its run), deepen iconic characters by thoroughly exploring their psychology and legacy, and construct a film that's less interested in "subverting" the saga or our expectations as it is in recontextualizing everything that makes the franchise so special in the first place.Most impressively, however, might be the fact that he even snuck in a fresh take on unrealism on top of it all.Thanks to Star Wars' relatively strict adherence to its own "house style" – familiar wipe transitions, John Williams' iconic score, evoking the Original Trilogy aesthetics as much as possible, you know the deal – you'd think that Rian Johnson could only go so far in making, well, a Rian Johnson movie. But in lieu of being hemmed in by limitations, Johnson seemingly embraced the challenge and utilized all his prior experience to make a film that deals with unrealism as less of a style or method of filmmaking, and more of a theme.Perception, misunderstanding, and the idea that our preconceptions have the power to be even more potent than reality itself – these offshoots of unrealism are emphasized again and again throughout every main character's journey in The Last Jedi.Never is this more assuredly on display than when we flash back to Luke Skywalker and Ben Solo's fateful falling-out, the night Luke failed in his mission to train the next generation of Jedi and the night Ben truly became the sinister Kylo Ren, no less than three separate times. When Luke first tells Rey his side of the story, he depicts himself as an overwhelmed Jedi master (sans lightsaber, notably) who was powerless to stop the Dark Side raging within young Ben. In stark contrast, Ben recounts being awoken to a vicious lightsaber-wielding Luke looming over him, ready to mercilessly strike down his unsuspecting nephew in cold blood. The truth, naturally, proves to be somewhere closer to the middle of these wildly contradictory memories. Already poisoned by Snoke's teachings, Luke's glimpse into Ben's Dark Side-ravaged mind leads to a brief moment of weakness where he considers taking the most drastic action possible. Ben, for his part, sees only Luke's ignited lightsaber and his conflicted expression before reacting violently and setting himself on a path to destruction.Rey herself isn't immune to such self-aggrandizing flights of fancy, since much of her arc is driven by a motivation to be validated as a person of import who belongs amid the overarching Skywalker drama she finds herself caught between. Her unfulfilling vision in the Ahch-To mirror cave demonstrates this perfectly and is precisely why the revelation of her parents as "nobodies" is so vital to her journey. Characters who get what they want without conflict or growth, of course, can barely even be considered characters at all – they become vessels of wish-fulfillment instead, which is the last thing that Rian Johnson's writing would ever be accused of.Poe, Finn, and Rose all find themselves learning lessons about reality vs perception as well. Poe's arc from an unthinking soldier with no regard for chain of command to a genuine leader in his own right (with a crucial assist from Laura Dern's heroic Amilyn Holdo) may have been slightly divisive, but exists as a thematic link to the Rey/Kylo/Luke triumvirate. The same applies to Finn and Rose, in which Finn's realization of the abuse and suffering underneath Canto Bight's decadent allure, as well as finally aligning his goals with the Resistance, pairs well with Rose's acceptance of Finn as a flawed individual with the best of intentions rather than a perfect Resistance hero.While some would insist that not all of this comes together in the tightest, most conventionally satisfying way, it's hard to argue with the fact that Rian Johnson's unmistakable fingerprints shine through every facet of The Last Jedi. As the eighth episode of the Skywalker saga, this sequel pays adoring homage to the franchise's storied past in order to light a new way forward. As the fourth Rian Johnson film, this rookie step into a much larger level of blockbuster filmmaking is evidence of an artist's commitment to adaptation and growth without ever once forgetting the qualities that made him such an outside-the-box hire from the beginning.Unlike its antagonist, Johnson clearly sees through the lie of "Let the past die" and instead brought the full weight of his previous films to this production. And at the forefront, as always, is that tantalizing twist on unrealism and the very tangible ways it can affect the world of Star Wars as well as our very own. Along with its many other joys, this makes The Last Jedi stand out as a worthy, indelible, and resounding chapter of the Rian Johnson story.

Knives Out

True to genre conventions, Knives Out opens with the mysterious death of the elderly Harlan Thrombey (Christopher Plummer), whose vast fortune and valuable assets – to say nothing of an argumentative family simply rife with motive and opportunity – immediately raises suspicions over foul play rather than the suicide it's initially ruled. This is where the eccentric Sherlockian, Poirot-esque private investigator Benoit Blanc (Daniel Craig, having the time of his life) comes in, recruited via anonymous tip to discern the murderer for himself.From one standpoint, this film represents a sort of full-circle return to the murder-mystery roots of Brick. One look at the marketing, however, makes it clear that Johnson's latest film is proud to stand on its own feet... as it should be. Gone are the faded blues and greys of neo-noir cynicism and in its place we're given a hilarious, lively, crowd-pleasing romp so devoted to genre that it would feel right at home in the pages of whodunits such as Encyclopedia Brown, The Hardy Boys, and any Arthur Conan Doyle or Agatha Christie novel.Freed from the confines of a pre-existing universe that largely dictates tone and aesthetics, it's safe to say Rian Johnson went in an interesting direction with his very next film – setting it definitively in the real world at a very specific moment in time. This is a relative departure from his previous efforts (ones not dealing with literal time travel or taking place in a galaxy far, far away, at least), where only the odd outdated cell phone or phone booth lifts the artifice in the otherwise timeless haze of Brick or The Brothers Bloom.Indeed, there's a certain amount of irony in his most recent film so blatantly tackling real-world issues of its time at this point in Johnson's career.Knives Out would seem to have the most aggressive relationship yet with unrealism, committing to a particularly extravagant tone while going out of its way to bring up Donald Trump's anti-immigration policies and directly remind viewers of current politics (Johnson, for his part, cites his inspirations as a major reason why he chose to do this). Of course, avoiding all mention of such would've made for a far more awkward spectacle – after all, a wealthy white family like the Thrombeys, all selfishly benefiting from their patriarch's legacy (sometimes illegally) and all in blissful denial of their privilege, naturally invites comparisons. Centering the proceedings on Ana de Armas' Marta Cabrera, a kindhearted Latina immigrant working as Harlan's caretaker who suffers through the Thrombeys casually racist remarks and patronizing dismissals with infinite patience, only makes the decision even more appropriate.In many ways, Knives Out plays like a synthesis of Johnson's prior movies. Not only is it topically linked to Brick, but it shares a similar tone to The Brothers Bloom, sweeping us up in an entertaining joyride before slamming on the breaks to hit us with tension-filled sequences and heavy emotional truths. As with Looper, unrealism once again feels baked-in to the plot of Knives Out as a result of a premise and genre that will assuredly inspire complaints about how "unrealistic" the convoluted, coincidence-filled, yet thematically satisfying answer to the central mystery is. And in a neat echo of The Last Jedi, we even get instances of unreliable narrators spinning memories to better suit their own narratives. Multiple Thrombeys situate themselves in the exact same place of honor next to Harlan depending on whose perspective is being told and, in one notable example, an action as simple as a Thrombey beckoning Marta to join the family during a party takes on a disturbingly different tone depending on which version of the story we're privy to.At their heart, all murder-mysteries are a search for truth itself, which is why (whether by choice, instinct, or complete happenstance) Knives Out serves as a natural testing ground for further delving into unrealism. Marta's dignified sense of morality gives us a solid foundation to cling to amid so much untruth and uncertainty; a foundation that barely ever crumbles, even after the reveal of her fatal mistake of unwittingly switching medicine vials and poisoning Harlan with an overdose of morphine. That Harlan would go to such great lengths in his final moments to protect Marta and her undocumented mother from suspicion and collateral damage, up to and including slitting his own throat to preserve the ruse, certainly helps keep us on her side as a standard whodunit suddenly turns into a game of running out the clock and hoping that Marta stays one step ahead of the relentless truth-hound Blanc.But in quintessential fashion, the other shoe drops only when the reading of Harlan's will positions unsuspecting Marta as the sole inheritor of the Thrombey fortune. As the surviving Thrombeys – who repeatedly claimed Marta herself as "part of the family", mind you – predictably descend into indignant chaos over this revelation, the main thesis of Knives Out rounds into shape: America will only be great once the ill-served working class of this nation, the genuinely empathetic among us who truly value their station in life, are duly rewarded for their efforts.That such a well-crafted, modernized whodunit was used to sneak such a message into a Thanksgiving release in the year 2019 to wildly successful results is remarkable enough – that final shot! – but Knives Out just might be the best proof yet of Rian Johnson's prowess in storytelling instincts, understanding genre, and exploiting unrealism to share his stories with the world.

Our Conclusion

"Hopefully with each thing that you do you're learning something, you're growing, and you're pushing yourself a little harder in some way or another. So I think you'd be in real trouble if each new thing that you create didn't feel like 'Oh, wow. I feel like I'm doing something a little different this time.' "Well after the release of Looper, Rian Johnson provided this answer when asked if its production felt any different in comparison to his first two films. If all this internet ink spent analyzing his five films has accomplished anything, hopefully it leaves you with the sense that each and every one was an example of a filmmaker learning from his past – both mistakes and successes – in order to bring something new and unique to the table the next time.Many of the loudest voices on social media during the past two years have already drawn their own conclusions based on a single one of his films, but a trip through Johnson's filmography paints a different picture altogether – that of a singular storyteller with a firm grasp on genre and tone who's forging his own decisive path.Even after all this, some still won't be drawn to this director or his work... and that's perfectly fine, as he would likely be the first to say that art simply can't be all things to all people. But for those who do find themselves on his wavelength, five feature-length gems full of heart, pathos, and the wholly distinctive style of cinematic unrealism have already been gifted to us. With any luck, we won't have to wait too long for the next one.