Buster Keaton Had To Do Some Digging To Rescue His Early Films

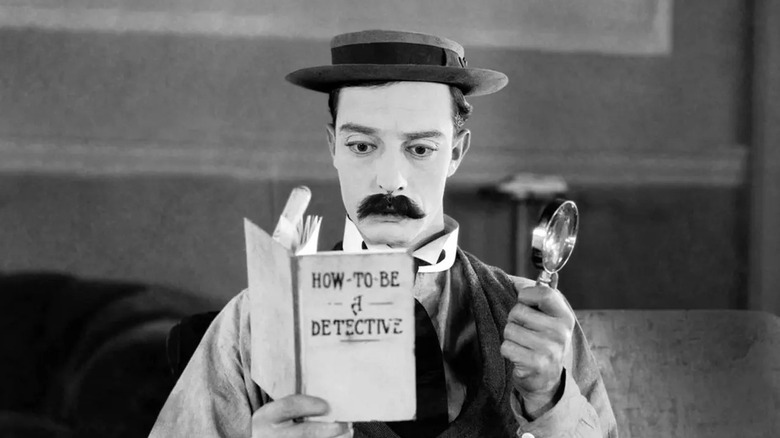

It's astonishing to see how the roster of silent clowns are still influencing how an entire medium is portrayed. From Charlie Chaplin to Harold Lloyd, each of them played an integral part in the pantheon of comedy in the silent era. The stone-faced Buster Keaton always ended up being my favorite. No one could replicate the dispirited look in his eyes, which usually hoodwinked anyone who came across his path.

Buster's experience on the vaudeville stage would ultimately prepare him for one of the most illustrious runs of the silent era. His brand of expressionless deadpan usually kept you at arm's length. You wouldn't know quite what he was thinking until he showed you with the kind of body language only he could pull off. He wasn't the only silent clown that got into stunt escapades. Out of all their daredevil exploits, however, Keaton's were among some of the most insane.

In many ways, Keaton's comedy endures because of the pure physicality that went into putting himself in life-or-death scenarios that will never be replicated ever again. Even a madman like Tom Cruise at least makes sure he's harnessed onto the side of a plane before it takes off, whereas Keaton would have grabbed on with his bare hands and hoped for the best.

That's why the comedic potency of Keaton's shorts, for the most part, will never die. The unfortunate thing is that as time passed on, so did the film stock deterioration of his work.

A compilation film brought Keaton back to theaters

In 1960, Keaton spoke with the Pulitzer Prize-winning Studs Terkel on his radio show about his career as a comic performer. Terkel asked him if there was any room for his brand of comedy in the modern sense, to which the "Sherlock Jr." star felt he was too old to pull off the same kind of stunts he performed decades ago. But rather than recreating the success of his earlier work, Keaton was intent on rereleasing them instead.

Amid a trip to Europe, Keaton had noticed there was a film that had been playing in several countries called "When Comedy Was King." It wasn't a movie, so much as it was a compilation that featured some of the greatest comedic bits from Chaplin, Fatty Arbuckle, and Charley Chase, along with some Laurel and Hardy. The film's director, Robert Youngston, spent his career throughout the '50s and '60s putting these compilations together for theaters with such titles as "The Golden Age of Comedy" and "The Big Parade of Comedy."

They exist mostly now as a curiosity considering it was most likely difficult to screen silent era filmmaking otherwise. Obnoxious sound effects were inserted to the gags, in addition to a grating narrator who flat out explains the jokes as they happen. It's the screen equivalent of the film bro boyfriend who leans over to their date and says "hey, that's Buster Keaton" when he shows up on screen.

Keaton was determined to hand over the prints that had been missing

When exhibitors asked him if he had any reels to offer up due to the resurgence of his popularity across Europe, Keaton was determined to give them the best. Keaton told Terkel that while he was in Munich, he had arranged to make duplicate negatives of missing prints that he had discovered:

"The original negatives have practically gone, but finding good prints of all these old pictures that I could get a good dupe negative off of and give them to them there in Munich, they will make me new prints, some with the subtitles of- in French, some in German, some in Italian, some Spanish, and some in English. And all we do is put a full orchestration music track to those silent pictures with no moderator and leave the old-fashioned subtitles in, put a good musical score behind them, and re-release them and this is going to happen within the next couple of months."

Keaton knew the timeliness of his shorts being out in the world. The re-release consisted of 10 feature films and 18 two-reeler shorts. It makes you wonder what Keaton's legacy would have looked like if these prints had once again seen the light of day. Film preservation wasn't exactly a high priority on the list. Most of them were destroyed after their theatrical run, so the fact that we can see them at all is a miracle unto itself.

If it weren't for James Mason, there's a great chance a lot of these prints wouldn't have been saved in time before their inevitable deterioration.

James Mason single-handedly saved a lot of missing prints

Keaton used to own a sprawling estate in Beverly Hills that he simply referred to as "The Italian Villa." He lived there with his wife at the time, Natalie Talmadge, who appeared in many of Keaton's films until their divorce in 1932. She won claim to the estate, but ultimately ended up selling it. Other stars had lived in the luxurious villa before "A Star is Born" actor James Mason purchased it. Naturally, Mason thought he was inheriting a magnificent estate, but little did he know there was a treasure trove hidden within the manor.

According to the LA Times, when Mason took over the "Italian Villa," he made an incredible discovery within his potting shed. It turns out that Keaton had left behind a whole slew of film prints that were just collecting dust. The two-reelers such as "The Play House," The Boat," "The Paleface," "Cops," "My Wife's Relations," "The Blacksmith," and "The Balloonatic" were rescued and set off for restoration. These prints were likely the ones Keaton used for his re-release strategy.

There were still other prints to be found, some of which would arise long after Keaton's death, but it goes to show that you never know where a lot of these prints might turn up, and if there's still more out there to be found.