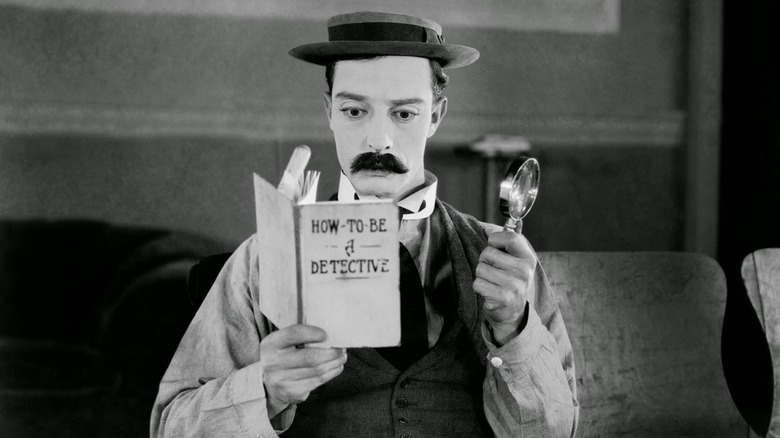

How Buster Keaton's Sad Man Schtick Became A Crucial Part Of His Comedy

One of the only photographs capturing Buster Keaton smiling is an early Vaudeville promotional still he took with his family when he was six. In the photos you'll see of Keaton in his cinematic heyday — the late 1910s to the early 1920s — his expression is flat, unsmiling, serious, and emotionless. He appears melancholy, defeated, stoic, mildly bemused, less-than-surprised, or completely nonplussed. His famed deadpan body language is the trademark of his comedy.

And yet, when one looks into the films Keaton wrote and directed, they will find a trove of impressive stunts, elaborate camera work, and scenes of utter danger. In 1926's "The General," Keaton was firing cannonballs. Keaton was also responsible for one of the most famous stunts in cinema history: For his 1928 film "Steamboat Bill, Jr.," Keaton stands up, facing away from a two-story house in a long shot. The house's entire front frame then fell forward in one giant plank, plummeting down toward the man below. Keaton managed to stand right on the spot where the second story's open window just happened to be, unwittingly avoided injury. It looked simple and off-the-cuff — but if Keaton had missed his mark by two feet, he would have been crushed to death.

Keaton realized early in his career that deadpan delivery, even in an elaborate comedy, was always going to be the secret to making audiences laugh. In a 1960 radio interview with the legendary Studs Terkel, Keaton talked openly about where he learned his comedy chops, and why he stuck with his shtick.

Learning organically

Terkel points out that, in 1960, Keaton's comedy had revealed itself as a primary influence among a lot of modern comedians. Although Terkel doesn't use the word "deadpan," he is clearly referring to Keaton's well-worn "sad" persona. Terkel muses that Keaton could easily join in with the modern kids and garner just as many laughs from audiences as he once did. Keaton demurely suggests that he, 65 at the time of the interview, wasn't spry enough to keep up. But Keaton did comment on how he discovered his famed stone face, saying:

"Well you see, I learned that from the stage, that I was the type of comedian that if I laughed at what I did the audience didn't. So I just automatically got to that stage where the more seriously I took my work, the better laughs I got. So by the time I went into pictures, not smiling was, was mechanical with me. I just didn't pay attention to it."

There was, it seems, no intended orchestration for Keaton. He wasn't scanning the Vaudeville landscape and seeking a new type of comedy that wasn't being done. He just, through years of performing, learned what audiences responded to. He stuck with certain techniques for a long while, and lo, a persona was born. The Keaton persona — the sad man — was versatile enough that he could be placed in any story or timeframe — a romance, a war film, an historical epic — and mine it for comedy. That kind of character is still the basis for comedy to this day, and one may find lessons on the topic taught at the Groundlings school.

Keaton vs. modernity

Terkel was eager to discuss comedic theory with Keaton, and spent a deal of the interview quoting from a book by Richard Griffiths and Arthur Mayer called "The Movies: The Sixty-

Year Story of the world of Hollywood and Its Effect on America."

Terkel is particularly interested in the notion of Keaton as an "old world" vanguard against an ever-encroaching tide of modernity. The book points out that Keaton's approach to the modern world is one of befuddlement. New technology seems to overwhelm the on-screen Keaton, and he tends to treat machines as people he doesn't quite understand. Additionally, Keaton has trouble relating to humans, and approached people as if they, too, are machines. Ultimately, Keaton's comedies could be interpreted as humanity rejecting mechanization. When asked to comment on this thesis, Keaton is pragmatic, pointing out that he only mastered "mechanized" comedy as a result of writing, directing, and starring himself. He said:

"Well, I guess that I found out I get my best material working with something like that. In other words, I was one of your original Do-It-Yourself fellas. I may not know how to do a carpenter's job, but I set out to build a house ... Well, everybody knows that you're going to get in trouble when you start that."

However one wishes to interpret Keaton's films, no one will be able to watch them without laughing. Keaton's abiding, expert, stunt-forward, sadness-background films are still as striking and hilarious today as they were nearly a century ago. He remains one of cinema's best.