Preparation Was The Key To Sidney Lumet's Filmmaking Style

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

If you have any interest in pursuing a career as a director, one of the first books you should read is Sidney Lumet's "Making Movies." It is not a heavily technical guide to the craft. Far from it. It's basically about how to set down a solid foundation that will allow you to withstand the vicissitudes of production. Lumet's process is a tad old-fashioned in that he cut his teeth in Off-Broadway theater before staging adaptations of plays for television. Lumet was not concerned with establishing a signature visual style. He was fixated on conveying the truth of the work. To do so, he prioritized rehearsal. Preparation is freeing. When you know what's expected of you, you can imbue the work with the unexpected ... within reason.

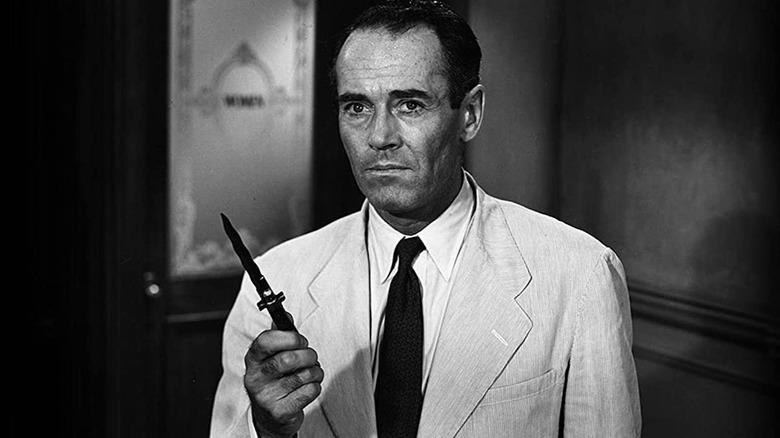

While Lumet was establishing himself as a top-flight filmmaker, he was saddled with tight budgets, which meant perfection was unobtainable. Take "12 Angry Men" for example. Lumet might've had Henry Fonda as a star and producer for the big-screen adaptation of Reginald Rose's pressure-cooker drama about jurors charged with deciding the fate of an 18-year-old boy who stabbed his father to death, but, despite the prestigious backing, his budget was a shockingly low $350,000 (equivalent to $4 million today). Whereas some young filmmakers might've tried to shoot for the moon on portfolio-boosting visuals, Lumet preached practicality.

Luck is the residue of design

In "Making Movies," Lumet bluntly punctures the notion of "movie magic." This is how the sausage gets made. As is the case on most films, Lumet shot piecemeal and out of continuity. "We went around the [deliberation room] three times: once for normal light, a second time for the rain clouds gathering, which changed the quality of the light coming from the outside, and the third time when the overhead lights were turned on. [Lee J. Cobb] arguing with Henry Fonda would obviously have shots of Fonda (against wall C) and shots of Cobb (against wall A)."

Simple enough, right? Not when your heavyweight actors — Cobb had originated the role of Willy Loman in Arthur Miller's "Death of a Salesman," while Henry Fonda was, y'know, Henry Fonda — are shot a week apart.

"But that's where rehearsals were invaluable," said Lumet, describing the hectic schedule:

"After two weeks of rehearsal, I had a complete graph in my head of where I wanted each level of emotion in the movie to be. We finished in nineteen days (a day under schedule) and were $1,000 under budget. Tom Landry said it: It's all in the preparation. I hate the Dallas Cowboys, and I'm not too crazy about him and his short-brimmed hat. But he hit the nail on the head. It is in the preparation. Do mountains of preparation kill spontaneity? Absolutely not. I've found that it's just the opposite. When you know what you're doing, you feel much freer to improvise."

Do right by your collaborators

"12 Angry Men" was Lumet's first theatrically released feature. He received an Academy Award nomination for Best Director, the first of four. He never won a competitive Oscar. This pleased Armond White, and Armond White alone. I've humored White's criticism of Lumet before, which is mostly rooted in the director's intuitive, make-your-days approach to filmmaking as described above. The Lumet of the '70s, the maestro who gave us "Serpico," "Dog Day Afternoon," and "Network," didn't have to worry a great deal about budget. He didn't just have stars, he had a track record. He could've been precious about his images. But the man loved actors, and if he had to cut on dialogue to enhance a performance, he'd do it without hesitation.

Art is messy. People are unpredictable. Cinema is, in its purest sense, a visual medium, but truth trumps purity when you're engaged in classical storytelling. Lumet could compose a shot with the best of them. Ned Beatty, framed to the left of center between those tiny green lamps in "Network," is seared into the brain of every card-carrying film buff. Lumet got it, and could go stone-cold Hitchcock if he wanted. But he was willing to sacrifice a meticulously constructed shot if his preparation favored a blessed accident. That's filmmaking. That's life. And that's why Lumet is one of the best to ever shout "Action." Even if you don't want to be a director, read "Making Movies." It's a beautifully pragmatic design for living.