12 Angry Men Ending Explained: Pride And Prejudice

Sidney Lumet's 1957 film "12 Angry Men" is required viewing for any Americans old enough to sit on a jury. More than just an intense character drama (although it is exemplary in that regard), "12 Angry Men" depicts a criminal justice system wherein thoughtful deliberation, context, crime, and class are all carefully discussed and considered during a murder trial. It's essentially a version of jury deliberation wherein everything seems to be working the way it ought to be — that means disagreements, that means confronting biases and prejudices, and that means considering the implications of how brutal and unjust it may be to sentence a young man to death.

And while it may be an idealized version of the criminal justice system, "12 Angry Men" is also very critical of it. The jury deliberation process, the film points out, is vulnerable to the lazy, disinterested caprices of ordinary people who would rather be anywhere else, and who accept that the death penalty is just sort of a natural, unquestioned part of all this. At the start of the film, most of the jurors think their murder case is so cut-and-dry, they have no problems with killing the defendant in the electric chair (the preferred form of execution used by the state of New York in 1957). It takes a full day of heated deliberation for some of them to realize that the death penalty may not be the best idea to mix into a criminal case.

Lumet, as far as I have been able to discover, never spoke out directly against the death penalty, but all throughout his career, his films were about how institutions are prone to corruption and lackadaisical expressions of banal evil, and how individuals who listen and understand one another can break that cycle. This was true in "Dog Day Afternoon," it was true with "The Verdict," it was certainly true with Lumet's corrupt cop dramas "Serpico" and "Prince of the City," and it's especially true of "12 Angry Men."

Prejudice. Wrote a Song About It. Like to Hear It? Here It Go!

"Prejudice always obscures the truth. I don't really know what the truth is. I don't suppose anybody will ever really know."

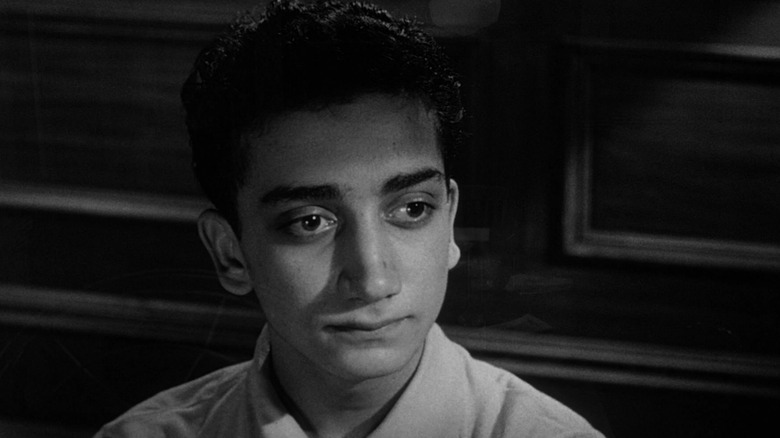

The story of "12 Angry Men" is simple: A young man is on trial for the murder of his father. There was a witness who saw the murder from another apartment, looking through the windows of a passing elevated train. Another witness says they heard the alleged murder and his father arguing shortly before the murder took place, and then claims to have seen him fleeing the scene of the crime down a staircase. The weapon — a switchblade knife — is unique and the murderer did indeed have a knife just like it. All the evidence points to his guilt. The accused man maintains that he was at a movie when the murder took place, and that he did not do it.

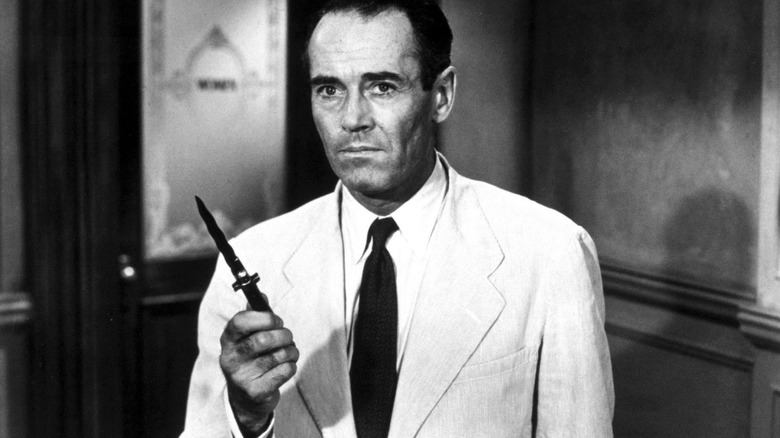

All this information is given in the hot, hot jury deliberation room where the entire film takes place. The unnamed jurors, mostly middle-aged, all white men, feel that this is a clear open-and-shut case of murder, that the deliberation will take no time at all, and that they can go home early; in one case, they'll even be able to make it to a baseball game. One of the jurors, #8 (Henry Fonda) feels that the stakes are too grave for the jury to merely speed past. This is about reasonable doubt, which he feels he has.

Over the course of the film, not only is each piece of evidence confronted and refuted, but so are the in-born prejudices of each juror. One raves about immigrants, and we see the assumption of guilt is based in racism. Another admits that he has a prejudice against people from the working classes. The old man in the room points out that we tend to dismiss the viewpoints of the old. Each one of them has to do some soul-searching in order to realize that they may not have a full version of the truth. Examining the fabric and strength of our own character is required when discussing the lives of others.

Juror #3

At the beginning of "12 Angry Men," the vote to convict — and to execute — is 11 to 1 with Henry Fonda being the dissenting voice. By the end of the film, and after personal truths have come to light, there is only one holdout in the form of Juror #3, played brilliantly by Lee J. Cobb. He is the most passionate about giving this kid the death penalty, and yells at other jurors for changing their minds. He really, really wants this kid dead. He accuses Juror #8 of being a "bleeding heart" (once a common term used by conservatives to decry liberal policies) and bellows about how sentimentality is blinding everyone. Juror #8 has, meanwhile, already pegged Juror #3 as a "sadist" and a "public avenger."

It was revealed earlier in the film that Juror #3 has a son about the defendant's age, but that they were estranged some years earlier. He talks about how "kids these days" don't call their fathers "sir" anymore. He tells a story about how, when his son was 9, he ran from a fight. Juror #3 was disgusted by his child's unwillingness to do violence, and vowed to "toughen him up." When the son was 16, he and Juror #3 got in a fight, and the son punched him in the face then ran away. They hadn't spoken in two years. "Kids," he says "you work your heart out."

In the film's final scene, Juror #3 redirects his anger from the other jurors to a picture of his son he had in his wallet. "Stupid kids, you work your heart out" he repeats. He then tries to rip up the picture, breaking into tears. It's then that he admits that the defendant is not guilty. Juror #3 has the worst kind of prejudice: Pride.

The Death Penalty

The history of the death penalty in the United States is checkered at best, often leaving the choice of whether or not to execute its citizens left in the hands of state legislatures. Michigan abolished the death penalty as long ago as the 1840s. In 1897, Congress ruled that it could be used to punish those convicted of federal crimes. Despite this, in 1911, Minnesota abolished the practice. After 1957, when "12 Angry Men" came out, six additional states were to abolish it as well. In the landmark 1972 case Furman v. Georgia, the death penalty was considered to be rife with racist leanings — Black people were executed far more than white people — and it was banned outright. Several states, however, re-worded their laws to gain access to capital punishment again, and by 1977, it was back on the table.

In 2022, 24 states still use the death penalty.

I mention all this because "12 Angry Men," while not arguing explicitly against the death penalty, is certainly an anti-death penalty film. If the American criminal justice system is anything like it was depicted in "12 Angry Men," then we understand that cases are being judged by flawed, prejudiced people who are fulfilling their own personal vendettas than committing themselves wholly to justice. And if that's the case, then maybe execution shouldn't be on the table. It could, however, be argued that "12 Angry Men" advocates the death penalty, but argues that it must be used only under the utmost of judiciousness.

I would argue that "12 Angry Men" should be shown in classrooms.