12 Best Horror Movies About Mental Health

The following article references suicide and suicidal ideation.

Horror movies have a long history of dissecting mental health. The 1920 silent film "The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari," for example, broke ground not only for its artistic achievement in storytelling but its boldness in delving into the recess of the mind and unearthing mental illness. Despite its portrayal of the mentally ill as villainous, it influenced the next 100 years in filmmaking. The genre continued to have an uneven relationship with its on-screen depiction of mental health and often missed the mark on the reality of daily suffering. Thankfully, there have been dozens of films that have dared to defy social norms and redefine mental illness, taking great care to humanize rather than demonize.

With the forthcoming "Mental Health and Horror: A Documentary," filmmaker Jonathan Barkan has enlisted a bevy of fellow creatives, spanning directors, actors, and horror scholars alike, to reassess his favorite genre. "Horror fans have long since been made to feel like there's something wrong with us for loving a genre that tries to be scary," he says in a Kickstarter promo. "But for many people, myself included, horror can be the medium for catharsis, representation, and even hope." Looking back at cinematic history, we have compiled 12 outstanding horror films that excel as chilling tales and showcase the struggle with mental health in beautiful, sometimes brutal detail. While the genre aims to terrify, it can comfort and heal. So take a seat, and dive right in.

If you or someone you know needs help with mental health, please contact the Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741741, call the National Alliance on Mental Illness helpline at 1-800-950-NAMI (6264), or visit the National Institute of Mental Health website.

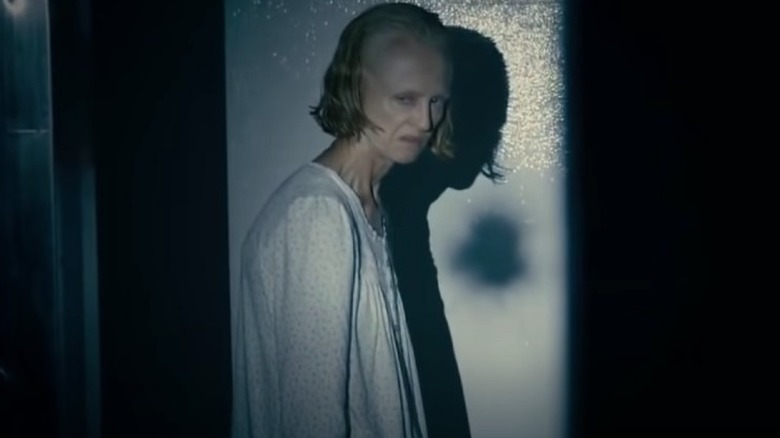

The Night House (2020)

"The Night House" expertly juggles chills and thrills with a devastating story about depression. Director David Bruckner takes great care to fill every single frame, either with palpable dread or raw emotion. With a screenplay co-written by Ben Collins and Luke Piotrowski, the film follows a young woman named Beth (Rebecca Hall) in her grief over the suicide of her husband Owen (Evan Jonigkeit). His death hangs like a shroud over her entire life, but that's not the only darkness following her around. Beth has long struggled with dark thoughts herself, but Owen's unconditional love kept her anchored in the present. His passing further opens the deep crevice running through her mind. Before long, what she determines to be her lover's ghost begins tinkering with her life through physical and auditory hallucinations. She suffers during her long days in the classroom, but the night seems even more suffocating.

What makes "The Night House" such a special feature is the weight given to the quieter character moments. While sitting at her desk one afternoon, a disgruntled parent of a student raises a fit about their son's final grade, eventually forcing Beth to reveal the cause of her absence at the end of term. It's a brief interaction that captures the film's entire thesis around the rippling effects of depression and suicide. It all boils over with the very last scene of the film — unleashing emotion so thick, you'd have to break it with a sledgehammer.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by dialing 988 or by calling 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

The Seventh Victim (1943)

"The Seventh Victim" masks a crushing story about depression and suicide with a cult overlay. Director Mark Robson brings a rich poeticism to DeWitt Bodeen and Charles O'Neal's script. From framing to mood-building, the film operates as a downright spooky tale on its own, but the rich thematic layers offer up something truly visionary. The story follows Highcliffe Academy student Mary (Kim Hunter) in a search to find her missing sister, Jacqueline (Jean Brooks). An initial investigation leads her to the cosmetics business Jacqueline once owned and has since sold to her assistant, an eye-raising decision that sends Mary further into a catacomb of mystery and intrigue.

Further conversations with other friends and colleagues, as well as a secret husband and a psychiatrist, reveals that Jacqueline suffered from mental illness and may have been involved in an underground cult. The nihilistic edge accompanies the dark spiral of depression. "The Seventh Victim," which features queer subtext, presents strangling mental health in simple terms. It neither sugarcoats nor romanticizes suicide and the end of one's life. It merely presents the tragic tale of Jacqueline in full, blinding light.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by dialing 988 or by calling 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

Daniel Isn't Real (2019)

Trauma drives "Daniel Isn't Real" and its central character. Director Adam Egypt Mortimer bases the dark and twisted story on a novel, titled "In This Way I Was Saved," by Brian DeLeeuw, who also co-wrote the script. The story focuses on Luke (Miles Robbins) and how witnessing a mass shooting completely derailed his life. In the aftermath, his mind created an imaginary friend named Daniel (Patrick Schwarzenegger) to cope. Daniel convinces Luke to grind up pills and put them in his mother Claire's (Mary Stuart Masterson) smoothie, thinking it will give her superpowers. Instead, she falls gravely ill from poisoning. Once recovered, Claire urges Luke to lock Daniel away inside her mother's old dollhouse, a symbolic gesture but one which carries great thematic power.

Years later, Luke struggles to balance school pressures and his mother's failing mental state. He worries he will fall into her orbit and become just like her. Daniel reappears after Luke unlocks the dollhouse, and things spiral dangerously out of control. "Daniel Isn't Real" contains all the reliable scares, but the real terror resides with its ability to capture the sheer tragedy of living daily with mental illness. Luke loses his grasp on reality and his ability to contain Daniel from wreaking havoc on the world. Daniel eventually takes over Luke's mental faculties and assaults a close friend. The world grows increasingly darker, leaving very little chance of escape. Sometimes, those who suffer don't get happy endings.

If you or someone you know needs help with mental health, please contact the Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741741, call the National Alliance on Mental Illness helpline at 1-800-950-NAMI (6264), or visit the National Institute of Mental Health website.

The Taking of Deborah Logan (2014)

In Adam Robitel's directorial debut, "The Taking of Deborah Logan," an elderly woman named Deborah (Jill Larson) is stricken with Alzheimer's disease and comes under the care of her daughter, Sarah (Anne Ramsay). Making a documentary about Alzheimer's and its effects on family, a film crew approaches Sarah about interviewing her mother. She's at first wary of their intentions and if her mother can handle the pressure. Sarah eventually agrees to allow the crew to document Deborah's daily life. Through a series of bizarre events, filmmaker Mia (Michelle Ang) realizes that something far more supernatural may be inhabiting Deborah and causing her erratic behavior.

Much like the disease itself, the story devolves into utter chaos when Deborah captures a young girl at the local hospital and hides away in the surrounding woods. Mia's research brings them to discover physician Henri Desjardins once attempted to perform a ritual to make him immortal, and it appears his spirit has returned to finish the job. "The Taking of Deborah Logan" is a rejuvenating entry in the found footage genre. It retools tropes and cliches to make an emotional, moving story about mental decay. A once vibrant, elegant woman slips from herself and transforms into a violent and unfeeling shell. The film is as downright terrifying as it is profound.

The Lodge (2019)

Religious trauma and mental anguish course like poison throughout Veronika Franz and Severin Fiala's psychological horror "The Lodge." When Richard (Richard Armitage) breaks things off with his wife, revealing plans to marry his mistress Grace (Riley Keough), she puts a gun in her mouth and ends her life. And that's just the opening scene. The film picks up six months later, and the Christmas season is well underway. For a quiet getaway, Richard invites Grace, along with his two children Aiden (Jaeden Martell) and Mia (Lia McHugh), to spend the holiday in a secluded cabin, nestled in the Massachusetts countryside. Winter is especially cruel this time of year and further illuminates Grace's gradual mental decline. Richard is soon called away back to the city for a work emergency, and he leaves Grace, Aiden, and Mia to get acquainted.

Well, that was his first mistake. Throughout "The Lodge," Grace experiences a nervous breakdown and relives traumatic moments from her childhood. Having grown up in a cult, her wounds easily reopen, and she tumbles into a pit of despair. Themes of gaslighting and human cruelty are also woven into the narrative to culminate in one of the most uncomfortable watches in recent memory.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by dialing 988 or by calling 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

If you or someone you know is dealing with spiritual abuse, you can call the National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1−800−799−7233. You can also find more information, resources, and support at their website.

The Haunting (1963)

In the same way as Mike Flanagan's "The Haunting of Hill House," 1963's "The Haunting" brings the emotional urgency, sorrow, and futility found deeply ingrained in the 1959 novel by Shirley Jackson. The film, later remade in 1999, excels in its subtle shades about mental illness, deterioration, and suicide through a classic haunted house template. Director Robert Wise gently nudges the audience into the story and supplies ample chills and nail-biting imagery. In relying on story and character, the scares come naturally as the characters poke around a lavish mansion in the hopes of uncovering its secret truth.

When Dr. John Markway (Richard Johnson) plans to investigate Hill House and its reportedly long, storied history with paranormal activity, he sends out invitations to those in the medical and psychic communities to get expert opinions. Only two respond — Eleanor Lance (Julie Harris) and psychic Theodora (Claire Bloom), who strike up quite an instant friendship. Bumps in the night play as vital a role in the story as does Eleanor's collapsing mind. As a young child, she once experienced terrible frights of the paranormal, and it has lingered in the back of her brain ever since. But now something far more insidious spills from her wildest dreams. It could be ghosts, or it could be a manifestation of her own wavering mental health. "The Haunting" is a beautifully drawn sketch about how illness is not necessarily loud and overwhelming. It can be just as muted and dull as ghosts rattling chains in a dusty attic.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by dialing 988 or by calling 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

We're All Going to the World's Fair (2021)

Director Jane Schoenbrun ties together the weight of mental health and the importance of digital spaces in finding community and connection. Billed as a horror/drama, "We're All Going to the World's Fair" uses conventions of found footage to tell a story about one young girl's desperation to be seen and heard. While living with her father, Casey (Anna Cobb) participates in an online viral trend called "World's Fair Challenge," in which a player watches a disturbing video and documents the effects. Casey doesn't experience anything out of the ordinary at first, but her mental state crumbles in the coming weeks.

Each of her video updates gets stranger and more troubling. Going by the initials "JLB," another online user reaches out to her and expresses concern over the latest upload, indicating that the online challenge has disastrous repercussions. The videos get even darker. One in particular shows Casey revealing intentions to either kill herself or her father with a shotgun. JLB grows increasingly alarmed, even when Casey claims she doesn't plan on actually following through. "We're All Going to the World's Fair" is a true roller coaster of emotion, highlighting the full breadth of depression and suicidal ideation in a way that feels haunting and raw and relentless.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by dialing 988 or by calling 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

She Dies Tomorrow (2020)

"She Dies Tomorrow" suggests that we are all terrified of the Grim Reaper deep down inside ourselves. While juggling collective mortality and an existential crisis, director Amy Seimetz delves into the incessant static of depression, as well. The film largely plays as a visionary thesis statement, less concerned about an overly intricate plot line than a message about hopelessness in the world. Kate Lyn Sheil plays a woman named Amy. And she is going to die tomorrow. If there's one thing she is sure of, it's that. Thoughts of death consume her entire being. She loses any sense of real purpose and simply resigns to the inevitable.

In her last 24 hours, she relishes everything in the world around her, from the feel of the carpet and branches on her lawn to the rush of a drunken ride in a dune buggy. Upon researching urns and leather jackets, she heads to a leather shop to ask about custom work as she plans to have her skin turned into a wearable leather jacket; but even that ultimately is unsatisfactory. She lumbers out to the desert instead. "She Dies Tomorrow" further connects anxiety with fear. Once one person comes into contact with another, they begin attesting to their own demise the following day. Paranoia is an epidemic, not unlike real life. Beautifully shot and composed, the film presents far more questions than it answers, and that is exactly the point.

If you or someone you know needs help with mental health, please contact the Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741741, call the National Alliance on Mental Illness helpline at 1-800-950-NAMI (6264), or visit the National Institute of Mental Health website.

Alone with You (2021)

Emily Bennett makes a powerful star turn in "Alone with You," an independent feature she co-directed with Justin Brooks. The low-scale horror picture was filmed during the early days of the global pandemic, so its cultural context certainly heightens the claustrophobic nature of the story. However, its thematic root stretches far and wide into issues of mental health, depression, suicide, and religious trauma. Bennett plays Charlene, a working makeup artist. With her girlfriend flying in from a work trip, she readies their apartment for a grand welcoming home to celebrate their anniversary.

On the surface, everything reads as normal, yet cracks around the edges tease a much different story. The hours tick by, and the paranoia swells to a suffocating level. Charlene leaves countless voicemails on her girlfriend's phone, lamenting where she is, and the walls bear down upon her shoulders. She begins hearing a blubbering cry from her vents, and her close friend Thea (Dora Madison) is too drunk to care. Her mother (Barbara Crampton) is a religious zealot, and an uncomfortable video call only adds fuel to the fire. Charlene slips further into her delusions, breaking down crying and believing herself trapped inside the apartment. "Alone with You" tightens the screws on mental turmoil in a way that's a remarkable feat, and the filmmakers make sure to bring plenty of unsettling dread and thrills to the mix, as well.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by dialing 988 or by calling 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

If you or someone you know is dealing with spiritual abuse, you can call the National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1−800−799−7233. You can also find more information, resources, and support at their website.

Dementia (1955)

"Dementia" is unconventional in every sense of the word. Director John Parker uses only stark imagery and composer George Antheil's lush, haunting score to relay the story. The film features not one line of dialogue. Only screams pierce through the pulsating soundscape when necessary. Instead, a sterling lead performance from Adrienne Barrett as Gamine carries the emotional weight. Gamine wakes up frightened in her hotel room after having the most god-awful nightmare. She self-soothes and then stumbles over to the mirror. She smirks in its glassy surface, retrieves a switchblade from her dresser and replaces it, and makes her way into the dark, dank city streets.

She meanders with no destination in mind, but soon meets a pimp, who tempts her into escorting an older gentleman around town for the night. She obliges. Naturally, the night doesn't go quite as planned. While in the cab between clubs, her mind spirals like a hypnotist's wheel and provokes a buried memory of childhood trauma. Her mind can't be trusted, and reality and fantasy blend together. Come to find out, she killed a man and had been so clouded in a mental hellscape she blocked it out. "Dementia" never makes Gamine out to be a villain; she's the definition of an antihero, a victim of herself as much as the outside world.

Lights Out (2016)

"Lights Out" gets the short end of the stick. Existing in the shadow of "The Babadook," released two years prior, the David F. Sandberg-directed feature bears a striking resemblance to the previous genre film in mood, tone, and theme. Where "The Babadook" deals heavily with grief, though, "Lights Out" focuses on mental health, generational trauma, and inherited conditions. Rebecca's (Teresa Palmer) relationship with her mother, Sophie (Maria Bello), hangs by a thread. Harboring unaddressed resentment and pain, Rebecca has moved out of the family home and left her brother Martin (Gabriel Bateman) in Sophie's care. One night, Martin witnesses his mother whispering to an unseen figure in the dark. Sophie later tells the frightened child that she was simply speaking to her friend "Diana."

Rebecca grows increasingly concerned about her mother's well-being and calls her out about not taking her medication. Tensions boil over, but that's the least of their worries. The dark entity latches onto Rebecca, and it becomes a race against time before it swallows her whole. "Lights Out" uses a malevolent presence to impart the inner struggle to navigate and overcome depression and dark thoughts. As we see with Sophie, these cycles can lead to complete destruction of really living and thriving.

If you or someone you know needs help with mental health, please contact the Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741741, call the National Alliance on Mental Illness helpline at 1-800-950-NAMI (6264), or visit the National Institute of Mental Health website.

Black Swan (2010)

Darren Aronofsky's "Black Swan" is a magnificent display of the role of art, as both a means to catharsis and an avenue to mental ruin. Tortured dancer Nina Sayers (Natalie Portman) desires to play the dual roles (as White/Black Swan) in an upcoming NYC ballet company production of "Tchaikovsky's Swan Lake." The theater's veteran ballerina begrudgingly goes into retirement, and the artistic director Thomas Leroy (Vincent Cassel) eyes a replacement. Nina auditions for the lead, and while she possesses all the elegance of the White Swan, she fails to command the stage as the Black Swan. Another dancer named Lily (Mila Kunis) owns both iterations in her performance and is subbed in as Nina's alternate in the unlikely event she can't perform. Pressure mounting, Nina questions her burgeoning friendship with Lily, who she believes intends to replace her in the show.

In true Aronofsky fashion, "Black Swan" is an arresting and disturbing visual feast. Nina suffers for her art every step of the way. Her reality skews as she delves further into the role, and when opening night finally arrives, it may be far too late for her to back away from the ledge. "Black Swan" is nothing if not a total mind trip.