Copyright Troubles Threw The Spy Who Loved Me's Script Into Chaos

James Bond was not in a good place in the mid-'70s. The classic film series had begun to flounder creatively, leading to a major box office disappointment, and separate financial issues had caused major fissures in EON Productions, the company behind the movies. A change was needed to give the character some new life, and in this case, the change would involve going back to the familiar.

Two movies in, Roger Moore (James Bond #3) had failed to make a real impression playing the famed spy, and the scripts reflected that, playing the hits of original Bond Sean Connery or forcing Moore through embarrassing pastiches of whatever genre pictures were big at the time — like blaxploitation movies and Kung Fu movies. 1974's "The Man With the Golden Gun" was a fairly major failure at the box office, one of the lowest-grossing entries in the whole series. It scored fairly high on /Film's Bond movie ranking, but its initial failure had a domino effect.

For its follow-up, producer Albert "Cubby" Broccoli, working solo on a Bond film for the first time, needed a premise. He already had a title: One uncharacteristic story from original Bond writer Ian Fleming called "The Spy Who Loved Me" was immediately evocative. But copyright issues made coming up with a story difficult.

Ian Fleming's shame

Ian Fleming, the novelist who created James Bond, pumped out books and short story collections on a near-annual basis from the mid-'50s to his death in 1964. The character was immediately iconic, from his taste in alcohol to his suave sadism. But Fleming had insecurities about the fame he found as a novelist, according to biographer Andrew Lycett. And he really didn't like his 1962 Bond novel, "The Spy Who Loved Me."

He had wanted it to undermine the character, and designed it around a random Canadian woman, Vivienne Michel, normal, unaware of the complexities of Cold War espionage. In the novel, James Bond appears briefly at the end, saving the woman from a terrible fate in an unromantic, violent way, just before the two have sex. Per Lycett, Fleming had meant for "Spy" to be a "cautionary tale" for the younger readers who had fallen in love with the character. He had even considered killing Bond off with the book. For his efforts, he got a hostile reception.

Out of some shame for the pans the book received, Fleming begged Bond publisher Jonathan Cape for a favor: no reprints, no paperback release. He wanted his grim failure to die on the vine. According to Bond website MI:6 HQ, Ian Fleming's embarrassment over the novel had led to his insistence that "if EON were to use 'The Spy Who Loved Me,' then they should take the title only and must come up with their own storyline."

Developing the script

Some 10 years after Ian Fleming's death, EON Productions was in need of a hit James Bond film, and producer Albert Broccoli decided to use that title as a springboard.

Broccoli's producing partner Harry Saltzman, with whom he had overseen every previous "official" Bond film, sold his stock in the their company Danjaq, Inq., the parent company of EON, effectively retiring from the filmmaking business in doing so. Broccoli was alone. He summoned a veritable army of writers to come up with something, anything, that could be the basis for the next entry in the series. Writers like John Landis (of "Coming to America" fame) and Anthony Burgess (author of the controversial "A Clockwork Orange") were commissioned to come up with drafts.

Veteran Bond scriptwriter Richard Maibaum kept only their best ideas. Bond's perennial number one enemy, the terrorist organization SPECTRE, would feature prominently as the villain, and the crux of the narrative would involve an oil tanker holding nuclear weapons. This was fairly standard material for Bond, quite like the Sean Connery films of the '60s. But both plot developments were caught in the heat of copyright disputes.

James Bond faced SPECTRE in the 1961 novel "Thunderball" and most of his '60s movies, beginning with franchise-starting "Dr. No." While Fleming's Cold War thrillers had largely used the real-life Soviet intelligence agency SMERSH as its league of evildoers, Saltzman and Broccoli had decided to switch it all to the fictional SPECTRE, all the better to keep the movies in the realm of escapist fun. But there was a problem with using SPECTRE.

The creators of SPECTRE

Fleming was not the sole creator of SPECTRE, as /Film documented. Two other writers, Jack Whittingham and Kevin McClory, had developed the idea for the outfit in conversations with Fleming about a James Bond film that largely went nowhere, according to Andrew Lycett's biography of Fleming. Legally, Fleming dropped all of his stake in the project after a certain point. When, a couple years later, the author decided to turn the screenplay concept into the novel "Thunderball," McClory took notice. He also took Fleming, then in the midst of major health issues, to court, with an eventual confrontation in 1963.

Lycett claims those health issues and the highly public nature of the case played a large part in his quick surrender, wherein all future printings of "Thunderball" would credit the other writers. McClory was therefore given the rights to all film versions of "Thunderball" and its consequent plot points, including SPECTRE. EON was able to incorporate SPECTRE (and its leader Blofeld) for a couple more movies, but wouldn't have the rights to include the organization again until 2013, when they greenlit a movie named "Spectre."

As Albert Broccoli brought on Christopher Wood to work on the Richard Maibaum draft of "The Spy Who Loved Me," Kevin McClory heard the news that SPECTRE would be involved. According to MI:6 HQ, the writer threatened legal action, as he owned the "sole rights to use SPECTRE and its agents." SPECTRE was out.

Nobody does it better

Christopher Wood's draft was completed, and one major plot point remained: a rogue oil tanker steals nuclear missiles and prepares to launch them at New York and Moscow, setting the stage for World War III. This became the plot of the movie, certainly a far cry from the low-key psychosexual intensity of Fleming's original novel. While no legal issues would keep the movie from being produced, MI:6 HQ claims that this idea was possibly plagiarized as well.

For starters, it was a fairly direct rip-off of Fleming's own "Moonraker," in which an ex-Nazi attempts to aim a nuclear missile at London. Additionally, Harry Saltzman had allegedly asked television producers Gerry Anderson and Tony Barwick to write an adaptation of "Moonraker" at some point in the early '70s. What they brought to the script included many elements that worked their way into the "Spy" screenplay, enough so that Anderson considered legal action but ultimately chose not to. As he claimed in "Gerry Anderson: The Authorized Biography," he was in too weak a position legally to fight the behemoth that was EON.

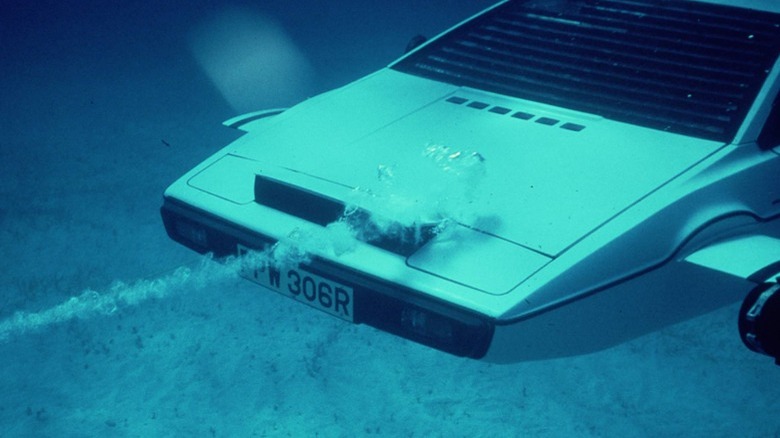

In return for the wild array of copyright issues faced to make "The Spy Who Loved Me" happen, EON got a strong James Bond movie, one that opens with maybe the best stunt sequence of the series and tells a nonsensical, but brisk, plot about nukes and a megalomaniac wanting to build Atlantis. It may not have had SPECTRE, but maybe that made it better.