The Daily Stream: Dear Brother Is A Masterclass In Melodrama

(Welcome to The Daily Stream, an ongoing series in which the /Film team shares what they've been watching, why it's worth checking out, and where you can stream it.)

The Series: "Dear Brother"

Where You Can Stream It: RetroCrush

The Pitch: Nanako Misonoo wasn't sure what to expect when she began freshman year at the prestigious Seiran Academy. She certainly didn't anticipate being picked for a coveted spot in the school's Sorority. But that's precisely what happens, transporting her overnight into a glittering world of byzantine scheming and desperate stakes. Every night Nanako writes to her pen-pal, a man she calls Brother. Slowly but surely she unravels the secrets of Seiran Academy, and the lives and burdens of its three great stars. The mysterious truant Rei "Saint Just" Asaka grapples with drug addiction; Fukiko Ichinomiya rules the Sorority with an iron fist; Kaoru Orihara is one of the most popular girls in school, yet despises the Sorority. As Nanako becomes tangled in their affairs, a great tragedy draws closer and closer.

Adapted from the work of Japanese comics legend Riyoko Ikeda by famous director Osamu Dezaki, "Dear Brother" is a '70s life-and-death school drama realized with impeccable style. Long inaccessible to English language audiences, the series was finally made available for streaming via RetroCrush. Now you, too, can understand what Nanako means when she says, at the end of every episode, "Brother ... these tears, they won't stop ..."

Why it's essential viewing

Anime is more popular now than it's ever been, in the United States and abroad. But that popularity comes with a very real presentist bias. Streaming sites promote new and exciting action series like "Demon Slayer" and the upcoming "Chainsaw Man," while older series are ignored. New viewers may be satisfied by the biggest hits. But sooner or later, they may find that what once seemed exciting becomes rote and disappointing. Instead of waiting for the anime industry to serve you a modern masterpiece on a platter, you may be better served digging through anime history for curiosities. Great anime continues to be made today, but some of the medium's greatest successes could only ever have been produced in their own time and context.

"Dear Brother" aired in 1991, predating modern classics like "Neon Genesis Evangelion" and "Sailor Moon." But it is also adapted from a comic that ran in 1975. Its creator, the artist Riyoko Ikeda, is part of the "Year 24 group," a generation of female cartoonists whose thematic and artistic ambitions revolutionized Japanese comics in the 70s. Her biggest hit was "Rose of Versailles," a retelling of the life of Marie Antoinette leading up to the French Revolution. The break-out star of "Rose of Versailles" was Oscar, a woman raised as a man. While she begins the series as Antoinette's bodyguard, her sense of honor leads her to join the revolution, where she dies storming the Bastille. If the great innovation of "Rose" was to reimagine the downfall of the French nobility as a tale of rich, bickering teenagers, "Dear Brother" asks, "what if high school students were as powerful and corrupt as the French nobility?"

I'll make an honest confession

"Dear Brother" is directed by Osamu Dezaki, one of Japanese anime's most famous auteurs. If you have watched anime produced for television, you have almost certainly seen a trick that he pioneered. Reusing the same footage multiple times in a row to convey intensity? That's Dezaki. White birds flying past windows to punctuate drama? That's Dezaki. Transforming an important scene into a watercolor painting? That's Dezaki. Dezaki's body of work is huge and varied, ranging from sports drama ("Tomorrow's Joe") to animal adventures ("The Adventures of Gamba") to action-packed science fiction ("Space Adventure Cobra.") He also directed the girl's tennis series "Aim for the Ace!" as well as, yes, the second half of the "Rose of Versailles" anime. Among his other accomplishments, his work permanently set expectations for how the melodrama of girls' comics would be translated to the screen in the following decades.

Dezaki began his career at Mushi Productions, directing episodes of "Astro Boy." All of Dezaki's innovations stem from circumventing the limitations imposed upon him by the studio, which was determined to make anime quickly and cheaply on a weekly schedule. Perhaps he could never have done it without Akio Sugino, a character designer and animator who would accompany Dezaki from "Astro Boy" to his masterworks like "Tomorrow's Joe" and "Rose of Versailles." Sugino ensured that Dezaki's characters would look consistently appealing, even if their animation could be stiff or even lifeless. While many in the anime industry today proudly count Dezaki as an influence, others label his work as "picture dramas" rather than real animation. Hayao Miyazaki would say with characteristic bluntness that "it was not just because of excessive expressionism that ["Tomorrow's Joe"]...was left behind the times and became a smelly corpse."

A part of me still imagines they might choose me

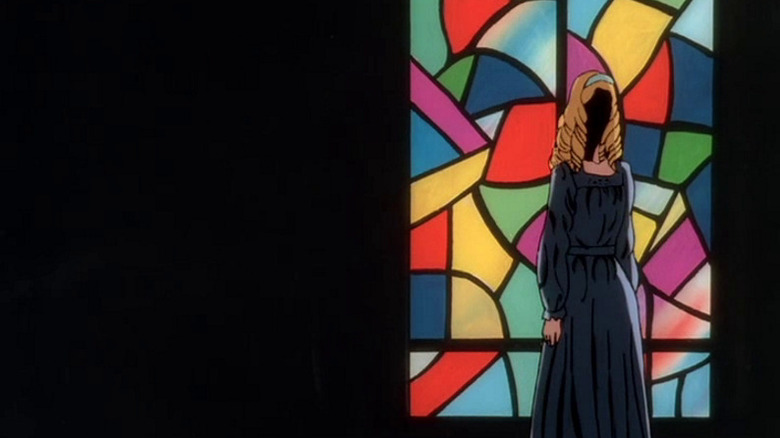

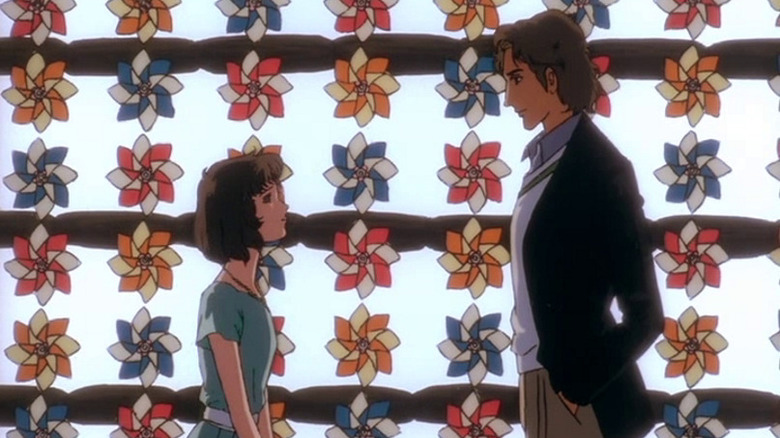

Those willing to tolerate Dezaki's eccentricities will find plenty to enjoy in "Dear Brother." The series contains some of the most memorable and decadent sequences in the director's career. Faceless teenagers stand in silhouette in front of stained glass windows. Flashbacks are staged against rows of turning pinwheels. Happiness, sadness, rage, terror, and guilt are all captured in exacting detail by freeze-frame illustrations, referred to by fans as "postcard memories." Once again, Akino Sujino translates Ikeda's character designs to animation, and supervises the animation itself for nearly every episode. The result exceeds even "Rose of Versailles" in its baroque imagery. If actual animation quality in "Dear Brother" is all over the place, its art design and storyboarding remain enchanting from beginning to end.

At the same time, "Dear Brother" makes creative decisions that only a director with Dezaki's prestige could get away with. Rather than set the story at the comic's publication date of 1975, or transplant the characters and setting to its 1991 airing, the staff has it both ways. The level of technology in the series is consistent with the early 1990s, and the characters wear clothes from that era outside of school. The anime is also much grander in scope than its source material, fleshing out three volumes of comics into a thirty-nine-episode epic. Very few modern anime adaptations would be as willing to risk angering fans with deviations of this kind. But remaking source material from the ground up to fit the needs of his team has always been Dezaki's way.

Quite extravagant and vain on the inside

Besides its distinct style, the best reason to watch "Dear Brother" are the characters themselves. It's tough not to sympathize with Nanako, who overcomes bullying and her own lack of confidence to brave the torments of Seiran Academy. Her best friend Tomoko is similarly likable as the only well-adjusted person in the bunch. But the real fun comes with the messiest inhabitants of Seiran, each of whom could anchor their own series. Nanako's classmate Mariko is especially memorable as a headstrong and manipulative teenager you either love or hate depending on the situation. The Seiran trio, consisting of Rei, Fukiko, and Kaoru, begin as god-like figures walking the academy corridors but quickly reveal themselves to be human beings. Fukiko may have the best character arc in the series, transforming from queen to monster to wounded child struggling to change. But my heart lies with Kaoru, who battles illness to liberate her classmates from Seiran's claustrophobia.

In addition to topics like bullying, suicide, and self-harm, "Dear Brother" tackles gender and sexuality. Both Rei and Kaoru dress like men and reject the norms of Seiran's all-female student body. Mariko refuses to even think about engaging in relationships with men due to her personal trauma. Rei becomes Nanako's first crush, while Rei herself has a deep past connection with Fukiko. While these emotions are handled carefully, the series ends in tragedy and a return to heterosexual "normalcy." Later comics and anime of the 1990s were daring enough to give their gay couples happy endings. But it bears remembering that "Dear Brother" was serialized in 1975, with accompanying strengths and weaknesses. (Those looking for further information on Japan's history of manga and anime about lesbian relationships, or "yuri," should seek out Erica Friedman's recent book "By Your Side.")

A spring rainstorm

"Dear Brother," then, is a mess of contradictions. It's a faithful reproduction of a pioneering 1975 school melodrama that drastically expands and remakes the source material. It has an instantly recognizable visual style that embraces its particular limitations, even if that means alienating modern audiences. It fearlessly depicts subjects on screen that remain taboo even today, but its vintage limits the way in which those subjects are handled. A modern anime fan would be more likely to recognize the progeny of "Dear Brother," like postmodern prog-rock opera "Revolutionary Girl Utena," then "Dear Brother" itself. Yet slowly but surely, the series has attracted an audience over the years. Once known to English-speaking fans only as a decades-removed follow-up to "Rose of Versailles," there are now critics who treasure the series as a great work in its own right.

As someone who loves "Revolutionary Girl Utena" and reveres the work of the Year 24 group, I think "Dear Brother" is revelatory. It can be old-fashioned and even retrograde in its way. But, sincerely, they do not make TV series like this anymore, in Japan or elsewhere. For those brave enough to take the plunge, I can only implore you to "be strong!" Just like Nanako says at the end of each episode, the tears will not stop.