How Come Drink With Me Created A Martial Arts Legend

Before they called her "Queen of Swords," Cheng Pei-Pei was a dancer. As a child in Shanghai, while waiting for her younger sister to finish ballet class, she would mimic the movements of the surrounding dancers. A teacher there was impressed and signed her up for classes. Before long, she was training in both ballet and traditional Chinese dance. After her family left the mainland for Hong Kong, an opportunity arose to join the Shaw Brothers, a film studio on its way to become one of the most important in the history of Hong Kong.

Cheng's fluency in Mandarin Chinese coupled with her dance background made her a natural fit. At that time, the Shaw Brothers specialized in musical dramas like "The Kingdom and the Beauty." They saw potential in Cheng to become another Ivy Ling Po, a Chinese opera film star. A role in 1964's Huangmei opera film "The Magic Lamp" set Cheng on her way. But fate had different plans for her. In 1965, the Shaw Brothers decided that the studio's future was not in Chinese opera, but in martial arts. The movies that would emerge from this period, tales of heroic martial artists joining forces against impossible odds, make up some of the best examples of the heroic "wuxia" genre on film.

The King and the Queen

In the years to come, critics would hail Cheng's "grace, agility and dignity, which...came from her background in ballet, music, and Chinese dance." Cheng possessed all these skills and more, but just as important a trait was her willingness to challenge herself. When the Shaw Brothers offered to train their crew in martial arts, Cheng jumped in head first. "I'm very proud, and competitive to a fault," she would later say in an interview with TimeOut. "I thought, if a man can do it, so can I." Cheng's spirit grabbed the eye of Runrun Shaw, one of the two Shaw Brothers, who immediately made the connection between her folk dancing prowess and a future career as a martial arts actor. Soon Cheng was given the lead role in a project that was to be a turning point in the history of Hong Kong film. That film was "Come Drink With Me," and its director was King Hu.

Despite having very different skill sets, King Hu and Cheng Pei-pei were actually quite alike. Like Cheng, Hu had left the mainland for Hong Kong. His fluency at Mandarin Chinese had won him a position with the Shaw Brothers as a set decorator. Also like Cheng, Hu did not set out to revolutionize the way martial arts films were made. His main skillset was acting, and he appeared in several films before apprenticing as a director under the famous Li Hanxiang. His first film was a propaganda picture meant to slam the Japanese, and his follow-up "Ting Yee-shan" was canceled once it became clear propaganda pictures were no longer profitable. The Shaw Brothers wanted a martial arts film, and Hu together with Chang Pei-pei were in the right place at the right time to make it happen.

Golden Swallow's unstoppable sword

Martial arts tales had existed long before "Come Drink With Me." Chinese classics like "Romance of the Three Kingdoms" and "Outlaws of the Marsh" depicted larger-than-life encounters between powerful warriors dueling to death. On the other side of the realism spectrum you had the equally important "Journey to the West," which in addition to its themes of Buddhism and enlightenment featured irrepressible transforming monkeys, magical tools, and man-eating bone demons. Early films made in China and Hong Kong had sought to capture the grandeur of these tales, but resorted to tricks to sell the illusion of supernatural human ability these stories required. "Fast or slow motion, footage printed backwards, animation..." According to the Harvard Film Archive, Hu avoided these tricks as much as possible. Instead he relied upon "the actual skills of his performers and the magic of editing."

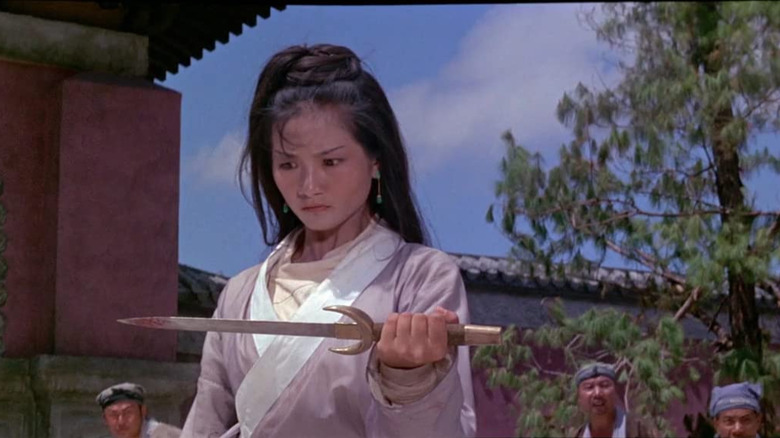

"Come Drink With Me" walks a careful line between realism and the supernatural. Cheng Pei-pei plays Golden Swallow, the child of a general seeking to rescue their brother from a bandit gang. She is introduced as a man, her actual gender only revealed later in the story. The character's introduction puts total faith in Cheng's athletic skill, trusting that her grace of movement coupled with detailed choreography would convince the audience they were witnessing a true martial artist at work. Watching the film today, the viewer senses immediately that Golden Swallow is stronger and faster than her peers, simply by observing the incredulous reactions of bystanders to the stunts she performs. Yet her performance remains grounded in physical reality, as does her villainous rival Jade Faced Tiger. Only Golden Swallow's comrade-in-arms Drunken Cat, and his nemesis Liao Kung, manifest abilities that are explicitly supernatural.

The shadow of Jin Yong

"Come Drink With Me" was not alone in redefining martial arts stories. Jin Yong's "Legend of the Condor Heroes," one of the most popular martial arts novels, began serialization in 1957. "Condor Heroes" borrows from past masterpieces, integrating historical drama, political and interpersonal conflict and some mythological elements. But like "Come Drink With Me," it grounds itself in a melodramatic realism. The characters and their relationships are at the forefront, and the supernatural is a hidden current under the surface of the world rather than a dominating force. "Come Drink With Me" is not a novel, and I don't know if anybody on set was an avid reader of Jin Yong. But I believe that these two works heralded a transformation in how these stories were told, creating a new paradigm upon which artists would riff for decades.

Another aspect in which "Come Drink With Me" and "Condor Heroes" broke ground is in their treatment of women. The hero of "Condor Heroes" is the naive but loyal male martial artist Guo Jing, but his soulmate Huang Rong steals the show. Huang is a quick and dirty fighter who resorts to trickery and poison, and while she loves Guo Jing too much to ever hurt him she happily plots circles around everybody else. "Come Drink With Me" similarly puts its heroine Golden Swallow front and center. For the film's first half, she plays the role of a headstrong martial arts hero without compromise. Complicating the scenario, Golden Swallow initially introduces herself as a man rather than a woman, introducing cross-dressing into the mix (Cheng had earlier played the role of a boy in her first film "The Magic Lamp.") Similarly, Huang Rong of "Condor Heroes" first befriends Guo Jing while dressed as a boy.

King exits, the Queen rules

That said, both "Come Drink With Me" and "Condor Heroes" only allow their female characters so much leeway. While Huang Rong makes a big impression in "Condor Heroes," the narrative truly revolves around Guo Jing. Similarly, Golden Swallow is poisoned halfway through "Come Drink With Me," at which point the reluctant martial artist Drunken Cat steps into the spotlight. Cheng Pei-pei comes back for the final battle, but the degree to which the narrative sidelines her character can't help but leave a bad aftertaste.

King Hu would evolve even further as a director in later films like "Dragon Inn" and "A Touch of Zen." These later two films are thought to be his true masterpieces, the high water mark of the wuxia genre on celluloid. But "Come Drink With Me" remains an important film, if only because of Cheng Pei-pei's performance. Hu took for granted she would star in his next film "Dragon Inn." Cheng would say to the South China Morning Post that "the costumes that had been prepared for that movie had my name on them." Unfortunately, "Dragon Inn" was to be made outside the Shaw Brothers, and Cheng was still on contract. Cheng chose to honor that contract rather than leave, because she was a "good girl" in her words. Cheng would never make another film with Hu, although they remained friends. In the meantime, her career continued to flourish.

"Ladies should be more refined"

Cheng's next big role was in "Golden Swallow." While named for the heroine of "Come Drink With Me" and supposedly set within the same world, the film was very different from its predecessor. With Hu having left Shaw Brothers, the job of director was passed to Chang Cheh. Just one year earlier Chang had directed the martial arts film "One-Armed Swordsman," which was as important in its own right as "Come Drink With Me." Chang would go on to become one of the most respected directors of martial arts films in the history of Hong Kong cinema. If Hu defined wuxia films at their most detailed and imaginative, Chang's hyper-violent masochism carved out its own bloody legacy.

Unfortunately, Chang was far less compatible with Cheng Pei-pei than Hu. He had rigid ideas about the difference between men and women, forbidding Cheng from performing stunts on set that she had simply taken for granted while making "Come Drink With Me." According to Cheng, Chang Cheh would say to her that "you're a lady, and ladies should be more refined." It was only through hard work and constant lobbying that Cheng was allowed to carry her own weight. Cheng had already compromised by returning to the role of Golden Swallow without King Hu in the director's chair. She refused to allow what she and Hu had created to be compromised any further.

The shadow of Cheng Pei-pei

"Around the time of Ricky Hui [in the 70s]," Cheng would say, "men started taking the lead and women became wallflowers." Slowly but surely, martial arts films were shifting away from the roles that Cheng had built her career on. But she would forge ahead regardless. Not only did Cheng collaborate with Chang Cheh once again in his film "The Flying Dagger," but she would continue to impress elsewhere in films like "Brothers Five" and "The Lady Hermit." After marrying in 1971, she ducked out of the film industry for a decade, but would return periodically to as a favor to old colleagues before starting again in television during the 1990s.

When Ang Lee hired Cheng to play the lead role in his Academy Award-winning film "Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon," it was with the full knowledge of Cheng's legacy and what she once represented. Once a dashing young swordswoman in "Come Drink With Me," Cheng plays the old, cunning martial arts tutor Jade Fox in "Crouching Tiger." Decades after the films that made her name, Ang Lee's film grapples with the same gender stereotypes that made Cheng's life increasingly difficult on set. The film never absolves Jade Fox, but the weight of Cheng's history is present in every scene.

The sword was a queen

"Swords are definitely my weapon of choice," Cheng Pei-pei once told TimeOut. "You can be more agile with it, unlike a staff." Cheng has wielded plenty of other weapons on the big screen, including whips and poison needles. But it is swords that have stuck in the memory. Not just because her dance experience lent her a unique athleticism. Not just because her break-out role, Golden Swallow, was a sword-wielder. But because Cheng Pei-pei is a sword in her own right. Direct, sharp-edged, forged in the fires of the Hong Kong film industry. Many have followed in her footsteps, to carve their own legacies in the history of film. But there is only one Queen of Swords.