Alfred Hitchcock Explains The Power Of Film Editing

Few filmmakers can claim the level of influence held by Master of Suspense Alfred Hitchcock. Talking about Hitchcock, Brian DePalma claimed, "if you wanna learn about cinematic storytelling, he's it" on an episode of "The Dick Cavett Show." DePalma owed his visual perfectionism and lurid narrative sensibilities to the director's work, but he also notes that Hitchcock crafted and perfected some of the fundamental grammar of filmmaking, especially in the art of cutting. His primary focus with editing, the very thing that led to his mastery of suspense, was in emphasizing one thing: the act of seeing. He used editing to show what characters see, how they see, and when they saw it.

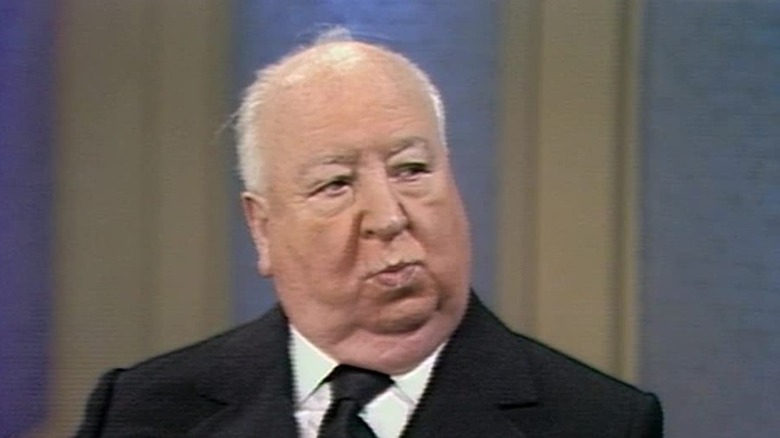

Hitchcock wasn't afraid of specializing in heightened gimmicks, like the one-take conceit of the Jimmy Stewart thriller "Rope" or the killing in the reflection of glasses in "Strangers on a Train." Even the classic "Rear Window" could be said by some to be an exercise in style more than anything. But as Hitchcock said in his own interview with Dick Cavett in 1972, that film best epitomized his narrative style by focusing specifically on one thing: using a character's point-of-view to reveal more about them and the story.

Points of view

That kind of visual storytelling, elemental as it is, even now feels uniquely direct. His famous concept of the filmmaking toolbox, with elements such as sound, color, and actors being pieces with specific functions, could have resulted in cold, overly-controlled films. The same could be said for his alleged overreliance on storyboards and pre-production (to the point where even he claimed the actual making of the movie was the worst part). But all of his movies teem with life, danger, and eroticism, sometimes all in the same shot. Much of that comes from what characters see and how they see it.

In the DePalma interview, Cavett notes that Hitchcock hated shots that placed the camera in fireplaces, an example of the kind of shot that disregards traditional point-of-view in favor of something sensational. He "always wondered who's in the fireplace." Hitchcock knew that a shot cluttered in the foreground would convey the perspective of a killer, and that giving the audience a taste of the killer's perspective was a way to show a hero was in danger. He also knew that letting the audience see what the character saw could put you directly in their shoes.

The Kuleshov effect

For Hitchcock, it's a question of object and subject. When you have James Stewart looking out a window, he's the object of the scene, shot evenly. But it's what you cut to next that leaves an impact: the subject of Stewart's gaze. If you cut to a child playing, and see Stewart smiling, he's a kindly older man. However, if you cut to a woman changing her clothes, and see Stewart smiling, he's a dirty old man. The subject ends up being the key component of the story being told.

Talking to Hitchcock, Cavett ends up referencing "The Kuleshov Effect," a filmmaking concept devised by Russian filmmaker Lev Kuleshov. Kuleshov's primary aim was to emphasize the power of cutting as the true innovation of the medium. In the most famous example of Kuleshov's work, the film cuts from the image of a warm bowl of soup to a stone-faced man, to a baby in a casket, to a woman lying seductively on a chair, and then, finally, back to the man. In all cases, the shot of the man is the exact same, but the moods conveyed by the subject of his gaze (sadness from the child, hunger from the bowl, and lust towards the woman) turn his stone face into a truly expressive piece of acting.

According to Vsevolod Pudovkin, who helped conceive the piece, the audience found the actor to be extraordinarily moving in all three instances. That his performance was technically just clever trickery ultimately demonstrated the value in the idea of the objective-subjective point-of-view style of cutting, a well Hitchcock went back to again and again.

Objective and subjective

You see it all the time in Hitchcock's movies. Not just "Rear Window," where the perspective of the hero is a key component of the plot, but in everything from the threatening state troopers in "Psycho" to James Stewart's obsessive P.I. studying San Francisco streets through his windshield in "Vertigo." The effect of a given scene can be paranoia, suspicion, or love, but in each case, it takes a master's delicate, patient hand to craft the narrative.

These cuts also let Hitchcock pace out the drip of information, building suspense by letting a viewer question what's going to come next. When Cary Grant unwittingly waits for an assassination attempt in "North by Northwest," the slow, even cutting from Grant's looks of confusion to mostly empty cornfields put the viewer in the character's headspace. The same could be said for the claustrophobia of "The Wrong Man," which uses the technique to cut from Henry Fonda's expectant gaze to endless shots of prison bars. In every case, Hitchcock finds new dimensions in the idea, transforming it from a technique into a filmmaking philosophy.