Rear Window Ending Explained: Spying On Your Neighbors Is Fun (Until It's Not)

There's something inherently voyeuristic about cinema. Just because you're peering into the lives of fictional characters (or, in the case of a documentary, a manipulated version of real events), that doesn't mean you're not still gaining some form of enjoyment from watching the struggles of others. But how do you explore this idea on-screen without making a movie that comes across as either a hypocritical exercise in the very thing it's critiquing or a tedious polemic?

Such is the magic of Alfred Hitchcock's 1954 classic "Rear Window," a mystery-thriller based on Cornell Woolrich's 1942 short story, "It Had to Be Murder," which is so riveting (as well as darkly funny and sexy) that it gets you quietly scrutinizing its characters' dubious actions — and, by extension, your own — without even realizing it. It's little wonder that similar thrillers still struggle to escape the movie's shadow nearly 70 years later, even when they bluntly tip their hat to it (as "The Woman in the Window" recently did).

James Stewart stars in "Rear Window" as L.B. "Jeff" Jefferies, an unmarried photographer who's itching to get back to work after being stuck for so long in his Manhattan apartment while recuperating from a broken leg. To pass the time, Jeff spends his days casually spying on his neighbors, including Lars Thorwald (Raymond Burr), a traveling jewelry salesman whose wife is chronically ill. But what seems like harmless fun to Jeff takes a sinister turn when he comes to suspect that Thorwald has killed his wife.

Watching Other People to Avoid Looking at Yourself

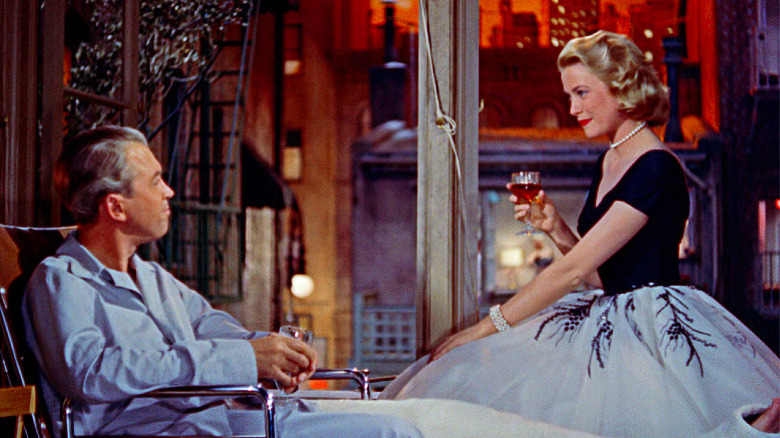

While all that is going on, Jeff is dealing with (non-homicidal) personal problems of his own. His girlfriend, Lisa Fremont (Grace Kelly), wants to tie the knot, but Jeff doesn't think their lifestyles (she's a socialite, he's always traveling) are compatible with marriage. More than that, Jeff fears that settling down will diminish his passion for his job and sow the seeds of resentment into his relationship with Lisa.

As Jeff watches his neighbors, he sees reflections of not just himself (a single pianist devoted to his work) but also Lisa (a young dancer he dubs "Miss Torso"), as well as what one or the other could become. There's a lonely woman he calls "Miss Lonelyhearts," a newlywed couple who almost seem to be prolonging their honeymoon to avoid dealing with their real life together, and a middle-aged married couple who lead a simple yet, by the look of it, happy life. Even the activities of the possibly murderous Thorwald echo Jeff's insecurities about his future.

Hitchcock shot almost the entirety of "Rear Window" from Jeff's apartment and often from his POV directly, pulling the audience deeper into his headspace and, in doing so, making them complicit in his questionable behavior. This also gets them to (be it consciously or subconsciously) check their own voyeuristic tendencies and wonder: is there anything they, too, are putting off by losing themselves in the act of "watching others?"

The Ending of Rear Window

Working with Lisa and his nurse Stella (Thelma Ritter), Jeff finds proof that Thorwald actually did murder his wife in the form of Mrs. Thorwald's wedding ring, which Lisa recovers by sneaking into Thorwald's apartment and nearly getting herself killed before Jeff and Stella call the police (who arrest Lisa for trespassing). Along the way, though, Thorwald realizes he's being watched and tries to murder Jeff by pushing him out the window of his apartment. However, in an ironic twist, Jeff is saved by the very thing that got him into this deadly situation: his camera gear. Although, he breaks his other leg for his troubles.

Ultimately, "Rear Window" paints Jeff's voyeuristic habits in a nuanced light, showing that they can be used to do good (like catching a killer) without ignoring the murky ethical and moral waters he wades into by casually invading the privacy of others. The film isn't interested in passing judgement so much as observing the peculiar habits of people and how their shared quirks can bring them together, much like Jeff and Lisa come to realize they really are kindred spirits thanks to, of all things, their morbid fascination with a suspicious neighbor.

Even better, its final scene reveals Jeff can now relax enough to take an afternoon nap in his apartment, with Lisa sneakily finding time to read a fashion magazine while he's asleep. Those two kids learned to share a life without sacrificing who they are after all.