After Yang's Colin Farrell And Director Kogonada On The Beauty Of Ordinary, That Incredible Dance Sequence & More [Interview]

"After Yang" may not be making as much noise as "The Batman," but the new film from "Columbus" director Kogonada absolutely deserves your attention. The film stars Colin Farrell and Jodie Turner-Smith as Jake and Kyra, a pair of parents who purchased a big brother android (Justin H. Min) as a way to instill more Chinese heritage and culture into their young, adopted daughter Mika (Malea Emma Tjandrawidjaja). Their family is forced to reflect on their relationship with each other and Yang himself when he suddenly malfunctions — and there doesn't seem to be a way to repair him.

Before the film arrived, /Film spoke with Kogonada and leading man Colin Farrell (who also crushes it as Penguin in "The Batman") to talk about the beauty in the ordinary that is so majestically presented on film in this story. Find out how Kogonada expanded a short story into a dramatically different feature film, hear what drew Farrell into the project, and discover the inspiration behind that amazing opening credits sequence with the entire cast dancing their hearts out.

"It was so crushing to even read it, to be honest with you, man."

I love this movie so much. I saw it when it played the virtual Sundance Film Festival, and then I had to watch it again just to really fully prepare myself to talk about it. This is just a tremendous movie that just crushed me in my very soul, it's so beautiful. I was curious, how did you approach this movie from the short story and add so many more elements to expand it into this deeper story?

Kogonada: Thank you for all of that. Well, the advantage was that it was such a short story. This is the first time I adapted anything, and I've heard that often it's the process of reducing, but here I knew that there was room and space to write things into it that I was wrestling with and cared about. So that was the starting point of it.

Also, Alexander [Weinstein], the author, was just so generous. He really was the perfect author. I hope to have that kind of experience again, because I went to his house, he made me some teas — he's a real tea connoisseur — and he was like, "Make this your own." So I think I knew that I wanted it to be more than a day. I knew that I didn't want memories purely to be flashback. So I knew that I was going to build something into this, the film space that would handle memory that way. So it was just a starting point, there were real incredible seeds to grow that story.

Colin, what was it about the script that attracted you to the story? Was there something specific that really just spoke to you?

Farrell: No, it wasn't specific, nor was it general. Just the script presented to me when I read it, just so many different aspects of the human experience: friendship, — love, romantic, familial, and parental — fear, inability to connect to yourself or to those around you, disappointment, shattered dreams, obviously mourning, grief. All these huge kind of issues. But they were presented in such a gentle and such a beautiful way. Not homogenized in any way. When I say beautiful, I just mean there was a certain grace to the way the script was written. There was a certain grace to the set that Kogonada created that we all inhabited for the two months that we shot. Yeah, it was just beautiful.

You said it was soul-crushing. It was so crushing to even read it, to be honest with you, man. Because as an actor, you approach a script, not as an actor. I mean, you do as well — you're thinking about yourself and "Is it something I want to do?" and "What's the pay?" All that s**t. Who's the filmmaker and all that stuff. But you're always reading it as just a human being, no more or no less human than you were when you were 4, 12, 28, you just have a little bit more language at your disposal. But I read the script, and I had to stop it on page 40 or 50 and go make a cup of tea for 15 or 20 minutes because I was surprised by how almost unsettling I found the gentle presentation of these really, really fundamental and really, really important issues that were being explored and given to me.

"What does it mean to be a construct of this racial identity?"

Absolutely. Kogonada, the short story deals a little bit more with the racism that exists in the population for these techno sapiens like Yang, but that doesn't really seem to be quite as present in the movie. Why did you make that choice?

Kogonada: I think this was part of the choice of kind of leaning into what I cared about. I certainly care about racism, and I do think it still exists in the way that there's Jake's own attitude towards clones. Again, I think it's a future — we were talking about this in another interview — but the history of race is that you just find the next "other" that we can all sort of gang up and suggest that they don't belong.

So that's in there, but it's interesting too, because Alexander, he's a white, lovely, progressive man in Detroit and he's writing it. My insight was he wrote these Asian characters and put it in a certain context, and as an Asian, what was really interesting is how much I identified with Yang, the android. There was something about his constructed Asian-ness that I knew that I could speak to, for Alexander and his lovely short, and I really love it. But I just thought, "Oh, I identify with this construct of Asian-ness." And that's kind of where I was leaning into to explore that. What does it mean to be a construct of this racial identity, and the longing that he has for it to be more than that? That's also the same space that I am in and find myself in.

How did you go about determining how to visualize the memory space for Yang and this movie?

Farrell: So beautiful.

Yeah. I haven't ever seen anything like it. It's ethereal, but it also still has a genuine representation of a futuristic computer. How did that come about?

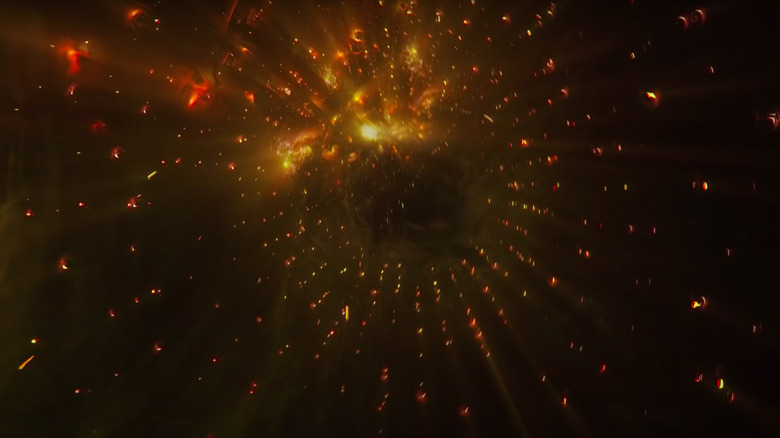

Kogonada: I knew that I didn't want it to feel like an interface we understood, like a desktop, "Oh, that's how we undo our files." I wanted Yang to be a mystery, even to me.The way Justin and I talked about is, "I don't know Yang, I don't fully understand." And I wanted us, when we entered into his memory, for us not to fully understand how that interface works, but for it to feel expansive and almost an evolving universe all its own. And it's also organic, I think, that some of it is like a fragment of his longing. There are trees and a sense of a place within his memory being built into this thing — you see him confess to Jake, that he wishes he had a memory of a place in time. So I loved that the memory itself was shaping itself into a sense of place.

"It was so moving to me because of the deep pantheon of unchecked memories that also exists."

Colin, were you given any inkling as to how that would be visualized, the things that your character was seeing in that space?

Farrell: No. A little bit on the day, I remember K saying there might be something coming up from the top corner or the bottom corner. I know that there were certain looks or head movements or gestures that weren't used, and I'm so glad they weren't used, that there was a simplification. Because I don't think the audience always needs to understand the technical aspects. Even though there's some pretty profound technology explored and touched on, I don't think the audience needed to understand exactly how I was accessing or which memory was I choosing. When I saw, it was an absolute shock to me. I had seen no renderings and had no idea of how it was going to look. It was so moving to me because of the deep pantheon of unchecked memories that also exists.

We go into this space, we hone into this one starlike glow, and then that takes the form of a memory that lasts three seconds captured. There's just some significant beauty or passing moment of profundity or normality. Obviously we know profundity can exist within normality, and that's somehow what this script is also about for me, is the beautiful moments in normality. But in the memory of going into Yang's memories, it's as much about that ocean of unchecked memories that exist out there and how rich his life was. His life was only really — I say it was "only really," but don't speak that badly, shallowly about Yang — but a lot of his life was built around the purpose of him observing the life of those he was there to provide a service to. Only through his observations can Jake really find his way back to the beauty of the life that he has been living, that he has ceased to be able to experience. So I don't know if that answers the question.

No, that's lovely.

Farrell: It was beautiful.

Speaking of those memories, Kogonada, how did you come up with the various visuals that you wanted to use to represent what Yang treasured himself? Obviously the memories with Mika and Ada are important, but there are so many peaceful, singular shots of him merely taking in the ordinary and finding the beauty in it. How did you determine what you wanted to shoot for that?

Kogonada: I think I just knew that Yang valued that. That there would be something about him attending to, like, hanging clothes or. So I think I always felt that there be a real sense of everydayness. His life was fairly limited, at least that version, by the time we get to Gamma, he's kind of within that house. So much of it is just of that house. So yeah, that was an interesting process, writing and trying to represent what he was collecting.

"I do see this film and this tale as a reference point to how I should never, for too long, go without slowing myself the f**k down..."

Did this movie at all shift your perspective on your own memories, whether it was shooting it or after seeing the movie? Because for me, this is a personal thing, but my father passed away last year —

Kogonada: Sorry.

Farrell: Sorry to hear that.

Thank you. I had been thinking about only milestone memories with him now that he was gone, and this movie made me key into the more ordinary, mundane memories with him. Did you find yourselves affected by that and viewing your own life in a different way because of that?

Farrell: There was plenty that I said was moving when I read the script and all, but I didn't have the power of imagination to find myself journeying down the road of being as moved by the memories that Yang captures. When I read it in the script form, it was lovely, and I could see what was being reached for, and it was very touching. But when I saw it in the film — even though it's a film that I'm in, and I don't usually get moved by anything that I'm in — I was so moved by it. And yes, I was reminded about myself, how there are really significant and important things that are happening around me all the time in relation to the world I inhabit, or the people that I love within that world, and my own thoughts or feelings that I observe in regard to nature.

But I'll fail for the rest of my days, because I'm not walking around going, "Beauty, record. How was I grateful? Life is quick. It's going. Be in the moment, be in the moment." I'm not, I get so lost sometimes, but I will and I do see this film and this tale as a reference point to how I should never, for too long, go without slowing myself the f*** down and trying to take stock of what the present is for me. Because it's ever fleeting. Ever fleeting, it's going too fast.

"I liked the idea of starting this film with all the families in sync, and then right afterwards, we see a bit of the dissolution of families."

Venturing into a little bit lighter territory. I wanted to talk about the opening credits for this movie because a lot of movies don't really have opening credits sequences at all anymore. This one is just so fun and it's so different from the rest of the movie. Can you talk about how it came together? And Colin, what it was like learning all of those dance moves and getting to do this with the rest of the cast?

Farrell: It was fun, man. It was really fun. It was a blast. The film has a somberness to it. It has a melancholy to it, which is what I love about this film, because it feels honest and it feels like it lacks declaration. It's certainly the furthest thing from hysteric in its articulation of the emotions and the psychology the characters are going through. So there's that, but then there's this kind of film within the film at the start, which is a few minutes long, the credit sequence of us doing this dance online. It's a global competition that tens of thousands of people are dancing in at the same time around the world, families, and they're trying to follow the moves they're being told to do. It was just a blast. It was a blast for us to get out of our heads and to just get into our bodies and have fun, f*** up in front of each other, and have to go again. It was a lot of fun. I don't know, maybe Kogonada can talk about that because it was his doing. It's his fault.

Kogonada: Yeah, I liked the idea of starting this film with all the families in sync, and then right afterwards, we see a bit of the dissolution of families. There's this film by [Yasujirō] Ozu, "Early Summer," that I really love. At the beginning of it, you just see this multi-generational family and they're not dancing, but they're in sync. They're making breakfast and you can just tell they've done this a hundred times, and then the rest of the film, it's going to be the last weeks of this family together. So that idea was in mind.

I'll be honest, I've only shared this a couple times, but there is this martial arts film that I watched, when I was a kid, by the Shaw brothers, and they have an opening sequence [that inspired this one]. It's called "Kid With the Golden Arm." It's suspended, and it's a credit sequence that has stayed with me. I showed it to Arjun [Bhasin, our costume designer], which is why they're wearing metallic suits, but each person, or gang member, is doing what their specialty is, and they're running the credits over it. That sequence has always stayed with me. So once I started imagining the studio, I showed them that intro sequence. I was like, I want it to be a dance, but I want to have this style of this.

Farrell: I got to watch this tonight, man.

Yeah, me too.

Kogonada: Yeah, it's great. It's a great movie too.

Farrell: It was lovely talking to you, man. I'm sorry for your loss again, brother.

Thank you. I appreciate that so much.

Kogonada: All the best.

The film absolutely helped me work through some emotional stuff.

Kogonada: That means a lot.

Farrell: All the best, brother.

"After Yang" is playing in theaters right now, and it's also available on Showtime.