North By Northwest Ending Explained: Hitchcock Rushes Through Mount Rushmore

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Throughout his legendary career, Alfred Hitchcock was a firm believer in the MacGuffin. The term's coinage is often attributed to the master of suspense, but it actually originated with screenwriter Angus MacPhail, who collaborated with the filmmaker on numerous films. It refers to the object or goal that plays an integral role in driving the plot's momentum, like the Death Star plans in "Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope," the Ark of the Covenant in "Raiders of the Lost Ark," or Hoke's dentures in "Miami Blues."

In Hitchcock's films, the MacGuffin's importance to the audience was secondary at best. The airplane engine in "The 39 Steps," Clause 27 in "Foreign Correspondent," and Ambrose Chappell in "The Man Who Knew Too Much" aren't wholly uninteresting in theory, but all viewers need to know is that being in possession of these items or simply knowing what they are is hazardous to the health of our protagonist, and the bad guys will pursue them to the ends of the Earth to obtain what they know and/or have, and, of course, eliminate them.

In "North by Northwest," one of Hitchcock's best films, the protagonist is the MacGuffin. This is not to suggest that Roger O. Thornhill, a twice-divorced mother's boy and successful New York City advertising executive, is of secondary interest to the audience. After all, the character is played by Cary Grant at the height of his singularly seductive movie star powers. Cary Grant is to be protected at all costs. But the man his pursuers mistakenly believe Thornhill to be, George Kaplan, is a non-entity. He does not exist. Ironically, Thornhill's inability to prove he is not this fictitious creation hurtles him through a breathtakingly perilous gauntlet that concludes with him becoming the best version of the man he has it in him to be.

What you need to remember about the plot of North by Northwest

"North by Northwest" is the platonic ideal of Hollywood escapism, a model of "and then" storytelling that keeps its plates spinning until the final shot. The film opens with Grant's committed bachelor Thornhill meeting up with a couple of business peers for a several-martini lunch at Manhattan's Plaza Hotel, where a bit of bad timing convinces some nattily attired thugs that he is the man who's been paged by the waiter: George Kaplan. Thornhill is kidnapped and left to die in a drunk driving accident, but the experienced tippler is able to drive himself to safety. It would seem to be a worst-case scenario for the men hunting George Kaplan, but they're prepared to improvise. So, too, is Thornhill, even though, while attempting to clear his very real name, he's burdened with the added weight of trying to ascertain the kill-worthy activities of the man he's believed to be.

Thornhill soon learns that Kaplan is caught up in some kind of intrigue involving a United Nations diplomat, whose murder gets pinned on him as well. The frantic ad exec manages to stow away on a train bound west to Chicago, where he eludes capture via the kindness of a drop dead gorgeous traveler named Eve Kendall (Eva Marie Saint).

At this point, Hitchcock and screenwriter Ernst Lehman have revealed to the audience that Kaplan is a decoy identity created by the United States Intelligence Agency to throw their adversaries off the scent of the film's second MacGuffin, vitally important microfilm hidden in a small statue. We haven't the slightest idea as to what this is, and we never will, because all that matters is Thornhill's safety.

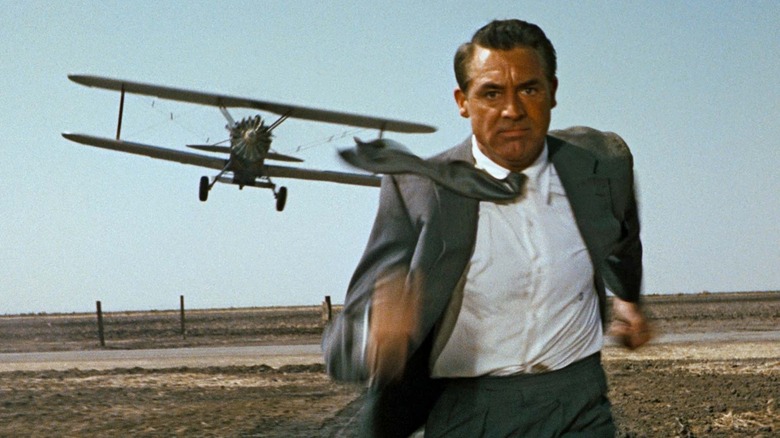

This elegantly brilliant plotting briefly leads the audience to think that Kendall has tried to get Kaplan/Thornhill killed by sending him to a rendezvous deep in Indiana farm country, where he's hunted in a masterfully shot, cliche-dodging suspense sequence by a machine-gun-wielding crop duster pilot. Is she in league with the bad guys? No. She's the operative being protected by the non-existent Kaplan, who, as far as these rogue operators are concerned, does exist in the form of Thornhill. When Kendall is captured by the villains, led by a suavely evil James Mason as Phillip Vandamm, Thornhill's mission is no longer just about saving himself. This moneyed mama's boy is sticking out his own neck to rescue Kendall.

What happens at the end of North by Northwest?

The finale of "North by Northwest" takes place in a mountain lair situated above Mount Rushmore (a setting that sparked a government controversy in real life), where Vandamm reveals all, save for what exactly is on that microfilm. Speaking of micro, Hitchcock none-too-subtly finishes off the minor narrative arc dealing with the unrequited affection Vandamm's ruthless henchman Leonard (Martin Landau) harbors for his boss, which has been hinted at throughout the movie. When Leonard blasts away at Vandamm with Kendall's blanks-loaded gun (which Vandamm believes is loaded), he's committing a crime of passion and last-gasp act of love all in one. Alas, Leonard sees too clearly, and he's rewarded with a sock in the face from Vandamm.

This rebuff becomes vitally important moments later during the film's celebrated chase across the faces of Mount Rushmore, where Kendall, clutching the statue, and Thornhill attempt to evade Leonard and another of Vandamm's lackeys. The sequence ends with Thornhill, grasping for dear life with one hand to the lip of a cliff, desperately trying to pull Kendall up to safety. He looks up to Leonard, who just seconds ago hurled Kendall into this predicament, and begs for help. Leonard tentatively approaches Thornhill, and we wonder if, having been spurned by Vandamm, he might do the right thing. Instead, he places the sole of his shoe on Thornhill's hand. Grant's anguished grimace in his moment is exceptional. He's survived multiple attempts on his life, become an honorable man of action rather than a martini-swilling ad hack, and this is his reward?

Fortunately, Leonard is shot from a distance by the authorities, But the removal of this obstacle still leaves Thornhill with the literal heavy lift of getting Kendall and himself out of this predicament. No one is in a more precarious position here than Hitchcock. In order to ramp up the suspense of this situation, the director has made it abundantly clear via close-up that Thornhill's grasp is nowhere near firm enough to support his attempted rescue of Kendall. Short of someone running to Thornhill's rescue, our eyes tell us that her goose is thoroughly cooked. How to resolve this?

Why the ending of North by Northwest means

In a leap of screenwriting and editorial magic, Hitchcock has Thornhill say, "Come along, Mrs. Thornhill" as our hero magically lifts her up to the top bunk of a bed in a luxury train compartment. In all of one or two seconds of screen time, the master has allowed his characters to cheat death, wed and head off on their honeymoon. This is akin to Hitchcock cutting away from James Stewart's terrified Scottie Ferguson, dangling from a San Francisco building gutter and on the verge of fainting, to the character sitting safely in Midge's living room in the opening scene of the previous year's "Vertigo."

Many have wondered by "North by Northwest" ends so abruptly in this fashion, and there's a simple answer: It's a slick trick that works because Hitchcock knows precisely what the audience wants and how to deliver the impossible without setting off their BS detectors. Interestingly, according to Lehman, the "Mrs. Thornhill" line dubbed in to satisfy the production code's aversion to unwed sex.

Hitchcock has time for one more cut at the end of "North by Northwest," and that's to the infamous shot of the train carrying Thornhill and Kendall speeding phallically into a tunnel. Even Eva Marie Saint herself commented on this final shot during a screening of the film at the TCM Classic Film Festival Road to Hollywood in 2012, saying (via Burlington County Times), "The first time I saw it was when I went to the opening. At the end, you can see a train go through a tunnel, and I said to my husband, 'That's a little Freudian, isn't it?'"

In the indispensable interview book "Hitchcock/Truffaut," the master observed this shot was "one of the most impudent shots I ever made." We know what's going on in that compartment, and all we can hope is that this time, having risked his playboy life to save the woman he loves, the ring never leaves his finger.