Year Of The Vampire: 100 Years Ago, Nosferatu Defined The Vampire Movie

(Welcome to Year of the Vampire, a series examining the greatest, strangest, and sometimes overlooked vampire movies of all time in honor of "Nosferatu," which turns 100 this year.)

Strictly speaking, "Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror" is not the oldest vampire film. There are other lost films that predate it, and still other extant works in which the vampire, or "vamp," serves as more of a proto-femme fatale, divorced of blood-drinking and many of the genre conventions that would arise after "Nosferatu."

The distinction that "Nosferatu" holds is that it is the oldest surviving Dracula movie, a landmark of the silent-film era and German Expressionism. F.W. Murnau's unauthorized 1922 adaptation of Bram Stoker's novel came a full quarter-century after the book's publication in 1897. Vampires were in the ether long before it, but with "Nosferatu," they crystallized in an image that still haunts: that of Count Orlok, the pointy-eared, raccoon-eyed, snaggle-toothed vampire, played by Max Schreck.

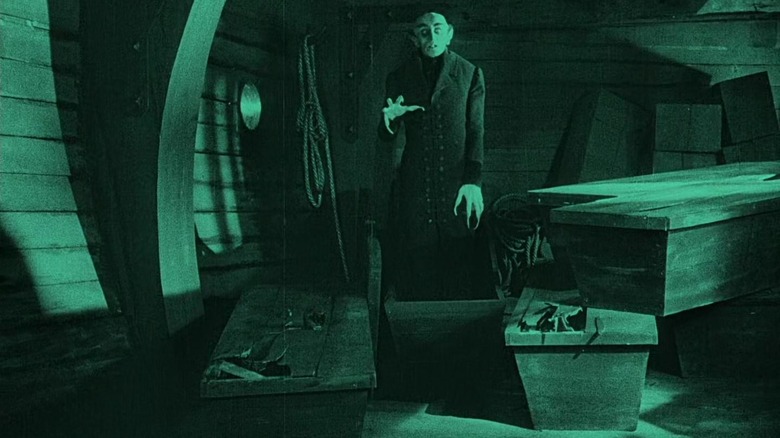

Even if you've never watched "Nosferatu," chances are strong that you've absorbed the sight of Orlok through film history osmosis. Maybe you've seen him sit straight up in his coffin, stretching his long, clawed fingers toward the camera. Maybe you've seen the low-angle shot of him with masts behind him on the deck of the doomed ship that ferries him from Transylvania to the fictional German town of Wisborg. Or perhaps you've seen him bent over the neck of Ellen Hutter (Greta Schröder) in bed.

One of the most evocative images in "Nosferatu" is Orlok's silhouette creeping up the staircase — a shadow that stretches long across the vampire movie genre. Orlok paved the way for a century of other bloodsuckers to move up those stairs into the public's imagination.

What It Brought to the Genre

Over the years, the vampire has functioned as a many-sided metaphor on celluloid. Prior to "Nosferatu," the vamp was a seductive figure, usually a woman who brought about a man's downfall in keeping with the retrograde gender politics of the time. "Nosferatu" brought out the more monstrous aspects of the vampire.

In Stoker's novel — which is in the public domain and available online for free via Project Gutenberg — the author gives a detailed physical description of Orlok's literary analog, Count Dracula, just prior to the famous line, "Listen to them—the children of the night. What music they make!" His Dracula has an aquiline nose, bushy eyebrows, sharp teeth, and pointed ears.

Orlok mirrors these features, the sum total of which form a rat-like visage onscreen, despite intertitles that liken him to "the deathbird calling your name at midnight." As the Jewish culture site, Alma, points out, Orlok also comes to Wisborg "surrounded by rats, an animal that Jews were frequently compared to in Europe at the time." His bald pate further aligns with antisemitic caricatures that were prevalent on the cover of dime novels and such in the early 20th century.

It's worth noting that a Jewish actor, Alexander Granach, plays a prominent role in "Nosferatu" as the Renfield-like real estate agent, Knock, who displays similar features and whose name recalls the myth of vampires entering homes by invitation only. In his autobiography, Granach wrote that Murnau was "always chivalrous" and defended him from antisemitic attacks. Whether or not the director consciously intended for Orlok to reflect stereotypes, the fact remains that prejudice was incubating in his country, where a deep-seated fear and hatred of the Other was taking root in the wake of World War I.

The Nosferatu Experience

"Nosferatu" bills itself as an "Account of the Great Death in Wisborg" — a reminder of Europe's plague-ridden past and our own pandemic present. The film has undergone multiple restorations and there are numerous versions of it floating around out there. While some may think of it as a black-and-white-movie, "Nosferatu" was "originally color-tinted throughout and only meant to be seen that way." This is why you will see it change color in some versions, with different tints denoting different times of day and lighting conditions or interior and exterior locations.

Act I of "Nosferatu" is devoted mostly to Thomas Hutter (Gustav von Wangenheim) and his sojourn to "the land of thieves and phantoms," an epithet that illustrates how the vampire myth was also entwined with prejudices against the Roma, who endured their own genocide in tandem with the Jews. Here, the locals are très superstitious, werewolves (really, striped hyenas) prowl the Carpathian Mountains at night, and Orlok himself arrives in a stagecoach to transport Hutter to his castle. Anyone familiar with the story of "Dracula" should have an idea of what comes next.

As the movie irises in and out of classic Stoker scenes, the incipient vampire tropes are all here: that of a creature who sleeps in a coffin by day, leaves bite marks on the necks of its victims, and dies when caught in the light of dawn. The title of Murnau's romantic, non-vampiric 1927 Hollywood debut, "Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans," almost reads like it's meant to be a morning antidote to "Nosferatu." For his part, Fritz Arno Wagner, who served as the cinematographer for "Nosferatu," would go on to provide the striking camera work for Fritz Lang's "M."

The Nosferatu Family Tree

Like any cinematic relic, vampire or otherwise, "Nosferatu" has to be situated within its historical context to be understood. The shadow of plague, xenophobia, and war hangs over it — just as its own slinking shadow, that Expressionist representation of evil, hangs over the vampire genre. Orlok came to Germany the year before Hitler's first failed coup. The Nazi Party had already formed two years before "Nosferatu" made its premiere in a Berlin zoo.

That some of Orlok's attributes may have been couched in pre-Holocaust demonizations of Jews only heightens the unnerving nature of the character, who would go on to influence a whole strand of less-glamorous bloodsucker depictions down through the decades — even as the vampire drifted from its questionable origins into other murky waters, such as the Antebellum South. The late Anne Rice's watershed 1976 novel, "Interview with the Vampire" notably depicted its brooding, undead protagonist as a slave plantation owner.

In 1979, Werner Herzog remade Murnau's film as "Nosferatu the Vampyre," with Klaus Kinski in the role of a Count who took back Dracula's name but kept Orlok's appearance. In 2000, "Shadow of the Vampire" even gave the behind-the-scenes legend of "Nosferatu" a meta treatment with a tongue-in-cheek tale that postulated Schreck really was a vampire and that's why he was so convincing. The film picked up two Oscar nominations, one for Willem Dafoe's acting and the other for the feat of make-up that helped bring his transformational performance to life (or undeath, as the case may be).

Whether it be the sewer-dwelling Reapers of Guillermo del Toro's "Blade II" or the coal-eyed Alaskan vampires of David Slade's "30 Days of Night," every time a filmmaker tries to make vampires scary again, they're pulling from the "Nosferatu" playbook.