E.T. Ending Explained: Spielberg Bids His Childhood Farewell

1982's "E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial" marked a shift in Steven Spielberg's directing career. It's not that his movies were impersonal up to that point; far from it, Spielberg has included pieces of himself in every feature film he's ever made (even the less than stellar ones). Yet, it wasn't until he told the story of a lonely boy named Elliott (Henry Thomas) and the lost little alien he befriends that it felt like Spielberg had really put his own life on the silver screen.

Over time, it's come to light just how much of his real childhood Spielberg and "E.T." writer Melissa Mathison poured into the film, from the way Elliott interacts with his siblings to Elliott's absentee father and the effect his divorce with Elliott's mother Mary (Dee Wallace) has on his youngest son. It remains one of the most autobiographical movies Spielberg has ever made and says so much about his upbringing while also speaking to the universal experiences of childhood — all of which has allowed the film to retain its power to move and enthrall audiences four decades later.

So why does Spielberg feel compelled to revisit that time in his life on-screen with his next directorial effort, a quasi-memoir titled "The Fabelmans?" To understand the answer, you have to look closer at how "E.T." creates a fictionalized version of the filmmaker's youth.

Exploring Childhood From the Inside Looking Out

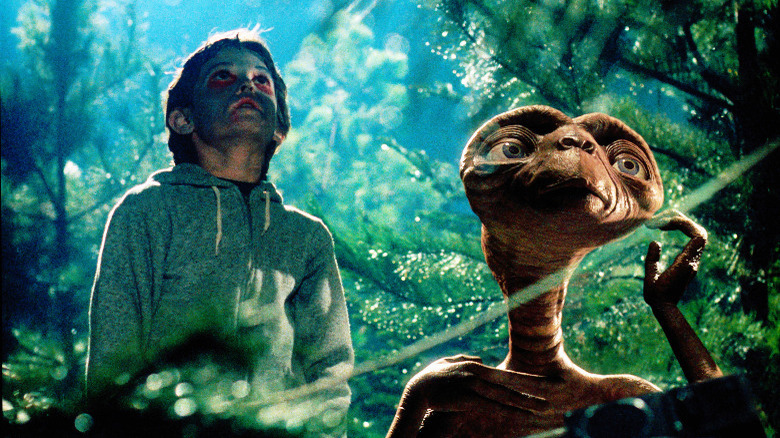

"E.T." revolves around the fantastical bond that Elliott forms with E.T. after the latter is stranded on Earth. Like an imaginary friend made flesh and blood, E.T. has super-human powers and can share his emotions with Elliott directly, providing Elliott with someone who understands him in ways he thinks his family does not and allowing them to work together to help E.T. contact his own kin. All the while, the duo are pursued by U.S. government agents led by Keys (Peter Coyote), a figure defined via the synecdoche of the keys on his belt.

The way "E.T." characterizes Keys before he meets Elliott is indicative of Spielberg's greater approach to the movie, which was to tell its story from the point of view of a child. This is why Mary is the only adult character given a proper name, as well as the only one whose face is shown clearly on-screen (or at all) until the third act. By doing this, "E.T." is better able to capture Elliot's limited understanding of the world visually and depict how he perceives the people and places around him.

However, because of the way it frames its plot, "E.T." also offers little to no insight into either of Elliott's parents, much less why they separated. It's these aspects of his childhood that Spielberg will likely focus on in "The Fabelmans," only this time from the outside looking in and not through the lens of a fairy tale.

What the Ending of E.T. Means

Over the course of their adventure, E.T. quietly teaches Elliott invaluable lessons that allow him to grow and mature, including how to be responsible for others, how to process grief and deal with personal loss, and how to ride a bicycle in the air (okay, that one's less applicable to adulthood, but it's an iconic moment). This all culminates in the movie's tear-jerking final scene, where E.T. bids Elliott a tender goodbye before pointing to his head and reminding him: "I'll be right here."

Suffice it to say, there's a lot one can read into "E.T.," and the way it operates as a coming of age parable. It's a story about developing empathy for others as you grow older, with Elliott learning to literally feel someone else's feelings for the first time. Similarly, scenes like the one where Elliott and E.T.'s mental link causes the former to behave erratically at school act as a metaphor for how confusing life is when you're Elliott's age, as you're beset by urges and desires you barely grasp.

Following that same train of thought, the ending to "E.T." serves as a touching reminder: sooner or later, we all have to say farewell to the parts of our childhood that made us who we are. Still, we can take comfort in knowing that they live on in our memories and will always be there by our side, much like a 40-year movie about a kindly, magical, other-worldly visitor.