The Only '80s Best Picture Winner That Roger Ebert Didn't Give A Perfect Score To

Movie-wise, the 1980s get a bad rap. Yes, the New Hollywood movement was put on life support in 1980 when Michael Cimino's hubristic (and utterly brilliant) Western epic "Heaven't Gate" had its plug pulled with Francis Ford Coppola's commercial fiasco "One from the Heart" (which is actually a masterpiece), but a new generation of film school brats like Spike Lee, Jim Jarmusch, and the Coen brothers stepped up to take cinema in exciting new directions. The artistic rebellion of the '70s wasn't quelled; it just went independent.

Meanwhile, Hollywood studios settled into a formulaic groove. High-concept blockbusters were all the rage, while prestige pictures grew loftier and ever more important. Just look at the decade's Academy Award winners for Best Picture. There are some great movies in the mix ("Ordinary People," "Amadeus," "The Last Emperor," and "Platoon"), but even those films came freighted with message-heavy significance. These filmmakers were dealing with serious ideas, and their movies could change the way you viewed the world. There was a void in your life if you didn't line up to see these highly consequential movies at your local multiplex.

Chicago Sun-Times film critic Roger Ebert, the most prominent film voice of the decade, bought what Hollywood was selling. He gave four stars to every single film that won Best Picture in between 1980 and 1989 — except one. Ebert gave Barry Levinson's 1988 Best Picture-winner "Rain Man" a three-and-a-half-star review. I think it's a much better movie than Oscar darlings like "Chariots of Fire," "Gandhi," "Out of Africa," and, dear god, "Driving Miss Daisy." Why did Ebert deem it the least of the '80s Best Pictures?

Roger Ebert struggled to comprehend the theme of Rain Man

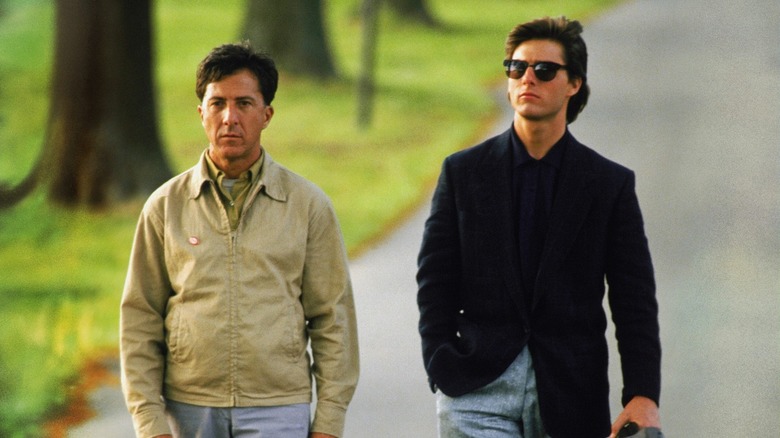

It's a three-and-a-half-star review, so, clearly, Ebert thought quite highly of "Rain Man." Tom Cruise has his star wattage dialed up to 11 as Charlie Babbitt, a sketchy Los Angeles operator whose business is going south in a hurry. He's gifted what appears to be an unexpected financial windfall when his estranged, wealthy father drops dead back East, but is only bequeathed an automobile. The old man's fortune is going into a trust for an autistic brother, Raymond (Dustin Hoffman), whom Charlie didn't know existed.

Hoffman disappears into the role of Raymond, but Cruise gives what remains the performance of his career as Charlie. He's a man who's gotten by his whole life on his charisma, and now the one person who could deliver him a desperately needed jackpot is impervious to his charm. Ebert identifies this dynamic in his review, but he seems more interested in the problem of Raymond. What's going on inside that brain? The opening paragraph to his review sets this up somewhat problematically. Per Ebert:

"Is it possible to have a relationship with an autistic person? Is it possible to have a relationshbip with a cat? I do not intend the comparison to be demeaning to the autistic; I am simply trying to get at something. I have useful relationships with both of my cats, and they are important to me. But I never know what the cats are thinking."

Obviously, our understanding of the autism spectrum has grown tremendously since 1988, but even then, I'd like to know what was going on in Ebert's brain when he decided to compare the brain of an autistic man to a house cat's, and suggested it's impossible to have a relationship with an autistic person! Bad Roger!

Otherwise, Ebert levels no real criticism against "Rain Man," but he does struggle to figure out what it's about. I'd prefer a puzzle like that to a bloated, pre-solved epic like "Gandhi" and "Out of Africa." And certainly to an old-woman-discovers-racism-is-bad travesty like "Driving Miss Daisy."