Oscar-Winning Director Steven Soderbergh Doesn't Read Reviews For A Good Reason

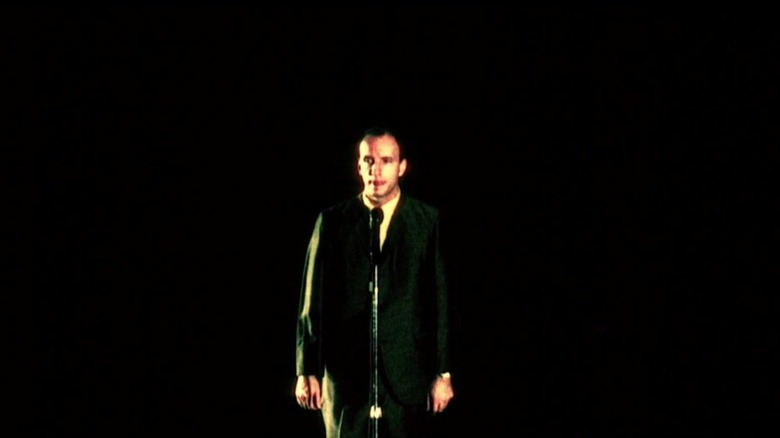

Steven Soderbergh has adopted a filmmaking ethos that allows him to be impressively prolific. Soderbergh can shoot and edit quickly, sometimes allowing him to release two films in a single year. In 1996, he put out his low-budget surrealist comedy "Schizopolis," but also the Spalding Gray monologue film "Gray's Anatomy." In 2000, he famously released two major Oscar contenders with "Traffic" and "Erin Brockovich." 2002 saw the release of his drama "Full Frontal" and his sci-fi epic "Solaris." 2009 was the year of both "The Girlfriend Experience" and "The Informant!," while 2011 had the two-fer of "Contagion" and "Haywire." Just this year, Soderbergh has already released the haunted house film "Presence" and the crime drama "Black Bag." The man can't stop.

Soderbergh was interviewed by the Suicide Girls website back in 2009 to talk about "The Girlfriend Experience," a film that starred celebrated adult actress Sasha Grey (no relation to Spalding). He said that he likes to work on instinct when shooting a movie. He doesn't stop to analyze or question his decisions. Soderbergh shoots quickly, figuring out shots as he goes. He says that he's "not a result person," but "a process person." He likes making movies more than he likes judging them in medias res. The director will only reassess a movie later, after it's already finished. "I want to make them for the amount of money and time that I've been given to make them, and then I just want to move on to the next thing without agonizing."

Of course, when one sees films as a process, it makes criticism seem churlish. A critic only sees the finished product, after it's been edited, completed, and released to the public. A critic, then, may begin to unpack what a film means, its sociological context, and how successful it was in communicating its message. Soderbergh, who was previously focused on the filmmaking process, knows that a negative review can't change what he already did.

Soderbergh likes to judge his movies on his own terms

If one is focused on results, of course, this is a very healthy way to think. It encourages a certain degree of practical filmmaking, reliant on finishing the day's work, not on highfalutin ideas of art or inspiration. Soderbergh seems unpretentious in this regard. He just wants to get the movie on film, solve the problems, and get on with his life. A critic, he feels, can't add to that process. If he made a mistake, a review won't alter that. And if one of his movies said something sloppily, or was a little unclear, that will be something Soderbergh will want to judge on his own. In his words:

"When I stop making [movies], then maybe someday I'll sit down and look at them and determine for myself what my success rate was. Right now, it's just not relevant. Except if you're making a certain type of movie — an art-house movie — and you know from a business standpoint that if you get terrible reviews it's going to be very difficult to get the audience to show up. But in terms of what they say, it doesn't change the movie. Pixels don't get re-arranged because a critic said something."

Many filmmakers don't like to read reviews for reasons of ego defense. If a critic lays into a bad movie, the director will only wince at the observations. Or a critic may bring an unexpected interpretation to their work that they didn't intend and couldn't have expected, making them feel that they didn't communicate their ideas well. Perhaps a critic will put their movie into a larger context they didn't consider, making them feel unobservant. Soderbergh simply doesn't have time for late-stage nitpicks on a movie he's already put behind him. "When one film comes out," he added, "I've usually already made something else, or I'm in the middle of something else, and my head has moved on."

Back in 2009, Soderbergh felt that movies were already over

The Suicide Girls interviewer asked Soderbergh about the fact that, even in 2009, film critics were being laid off from major newspapers en masse. A lot of local papers were folding at the time, and print journalism was finally seen as a dying medium. Soderbergh didn't like to see people losing their jobs, but he did acknowledge that film criticism had become too widespread to be taken seriously as an art form any longer. Technology, he said, made everyone a published critic, and the days of singular, iconoclastic critics — he cites Pauline Kael as his example — are long over.

But, more vitally, Soderbergh said that film was kind of dead. He felt that films still could influence people, but that other newer media had supplanted movies as the most important art format of our age. He said:

"[Movies] are more influential than they've ever been and less important than they've ever been. They're influential in terms of how people act and how they dress, and also what they laugh at. But in terms of importance? In terms of what they can do for us, how they can enhance us? I think they've never been less important than they are right now. There was a period of time when that wasn't true, but that time has passed. I think it's still the dominant art form, but I don't think it's an important art form anymore."

And if movies are no longer important as an artistic force, then what use is a film critic? Films are now a mere commodity, one of many commercialized art forms, cluttering up American culture. Some break through to a mass audience and become a viral sensation we can share. But in terms of spearheading artistic movements, influencing people's thoughts on a mass scale, or actually shaping the country's culture for the better, film has been dead for a while. Soderbergh made that statement in 2009. One might wonder if his view has changed or only been enhanced in the last 16 years.