You Can Thank This Classic '70s Anime For Studio Ghibli's Style

Studio Ghibli is one of the most beloved animation studios of all time, foundational in the rise in popularity of anime both in Japan and internationally. Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata have been responsible for some of the best anime movies ever made, no matter what metric you use to judge that.

But as famous and popular as their work with Ghibli is, Takahata and Miyazaki's pre-Ghibli work is just as important. The duo (but particularly Takahata) had already established themselves as legends in their own right, with movies and TV shows that challenged what was thought possible at the time. They drew inspiration not just from Walt Disney's work, but also from French animation and the emerging Soviet landscape. They created something unique that continues to inspire animators (and live-action filmmakers) everywhere. I've already written about some of Miyazaki's pre-Ghibli work and how unique that work is, but there is one particular show that — above all else — set Miyazaki and Takahata on the path to establishing their respective styles within Ghibli.

That show is "Heidi, Girl of the Alps."

Takahata's masterpiece is Heidi, Girl of the Alps

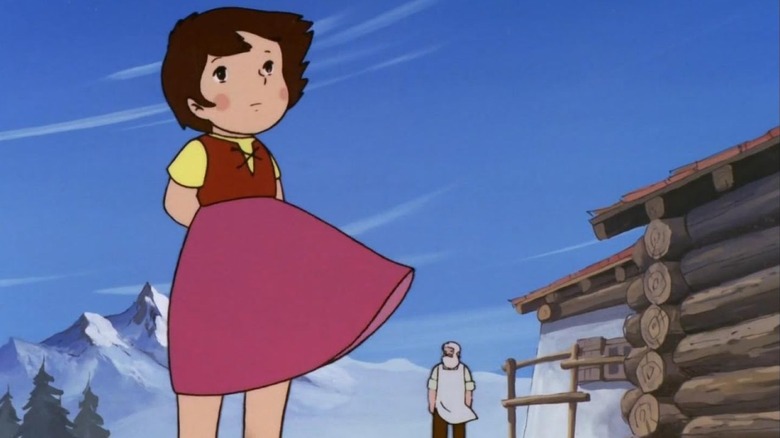

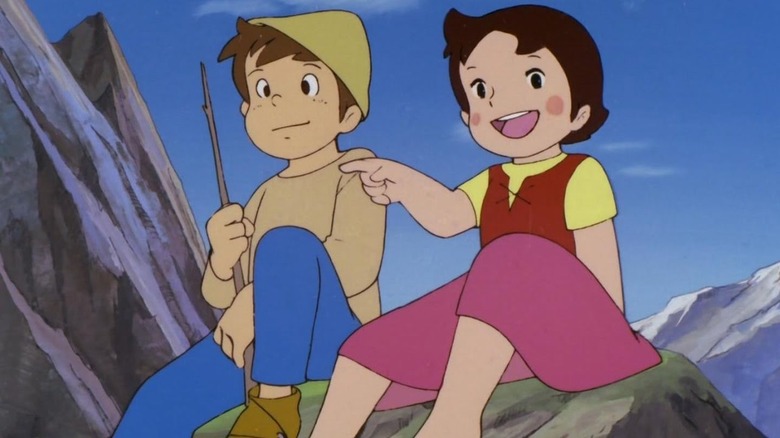

Produced by Zuiyo Eizo (now known as Nippon Animation), "Heidi, Girl of the Alps" is based on Johanna Spyri's "Heidi's Years of Wandering and Learning" from 1880. Isao Takahata directed the show and led a team that included numerous legendary animators, including Miyazaki (who contributed to the scripts, scene design, and layouts) and even "Gundam" creator Yoshiyuki Tomino (who worked on scripts and storyboards). The show followed the daily life of Heidi, an orphan who is sent to live in the Alps with her grandfather.

The series was recently the focus of an article by Animation Obsessive, who points out the uniqueness of the anime and how important it was for the future of Takahata and Miyazaki's careers. Indeed, from the very beginning, it was clear this would be an anime series like no other. Unlike Takahata and Miyazaki's previous works, there would be no fantasy or even just over-the-top stories in "Heidi." This was going to be a show that aimed for brutally unapologetic realism. Instead of flashing lights and lots of noise that was common in TV animation at the time (and still is in many countries), "Heidi, Girl of the Alps" dialed back the drama, telling mundane stories with a focus on tangible realism.

As Miyazaki said in an interview published on the Blu-ray set for "Heidi, Girl of the Alps," the goal was to create something that "accurately depicted the foundations of daily living." This, at the time, was near unheard of. After all, animation excels at the fantastical, which this show doesn't have. According to Animation Obsessive, Takahata initially thought that the adaptation was more fitted to live-action. Still, they pushed through and used live-action techniques to create something new, a show that would force the viewer to pay attention. Wide shots were common, as were scenes devoid of dialogue, forcing on empty space, and just character acting.

The result was a monumental success. Not only was "Heidi, Girl of the Alps" a huge hit in Japan, but also internationally in countries like Spain (which had its own comic book adaptation of the series) and the Middle East. The anime is credited with making Japanese tourism in the Swiss Alps popular (when I visited the house that inspired the original book by Johanna Spyri near Zurich, it was full of merch for the anime). In the Ghibli documentary, "The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness," Miyazaki called this show Takahata's "masterpiece."

A show instrumental to Ghibli as we know it

Despite how successful and well-made it was, "Heidi, Girl of the Alps" also brought unbearable working conditions to its staff. Miyazaki reportedly drew 300 layouts weekly, sketching characters, compositions, backgrounds, and even camera directions for shots. Miyazaki once described working on the show as being in a state of emergency as your normal condition. Granted, this wasn't uncommon at the time, but it meant that both Miyazaki and Takahata were growing disillusioned with what work would make these conditions worth it.

With the success of "Heidi," the studio started adapting more and more literary works through its "World Masterpiece Theater" series — eventually adapting works like "Les Misérables" and "Little Women." But that success, and the pressure to repeat it through other adaptations (such as "3,000 Leagues in Search of Mother") made Miyazaki realize he craved fantasy worlds, while Takahata leaned toward even more realism, feeling that "Heidi" had veered from that initial plan. The two men, partners for years, started drifting apart creatively, as their personal tastes and styles evolved with time.

This led to Miyazaki escaping realism by directing "Future Boy Conan," an anime that featured characters that felt tangible and real, but inside a fantasy world. Takahata, however, got hired to adapt "Anne of Green Gables," which he turned into his least idealized project yet, a work that went for full objectivity in its realism.

This is to say, we see the way both men worked within Ghibli in what happened right after "Heidi." Takahata's love for realism and objectivity, as well as Miyazaki's love for magical realism, can be seen clearly in the bizarre double feature of "Grave of the Fireflies" and "My Neighbor Totoro." This would become their signature style, with Takahata striving for grounded stories (even if he did direct the movie about raccoon dogs that use their testicles as parachutes) while Miyazaki went for more fantasy.