The 15 Best Movies On Tubi Right Now

You may or may not know this, but Tubi is an amazing streaming service. Sure, it's ad-supported, meaning you'll get a couple of commercial breaks during viewing, and no one's championing Tubi Originals. But no other streamer has a library as eclectic — mixing classic cinema, foreign films, studio hits, cult genre junk, horror favorites, and more. Where else can you find "The Red Shoes" next to something called "Dinocroc vs. Supergator"?

Tubi is like the niches of every other streaming service rolled into one, and it regularly hosts some of the greatest American and world cinema — for free, aside from the occasional ad break. Keep your Netflixes, HBO Maxes, and Criterion Channels — if I could only have one, I'm keeping Tubi.

Here are the 15 best movies on Tubi right now.

Jaws

There's a lot to say — and that has been said — about "Jaws": that Steven Spielberg was just 27 when he redefined theatrical releases and invented the summer blockbuster; that the escalating Hitchcockian tension in a beach town desperate for tourist dollars is brilliantly mounted; that Bruce the shark remains one of the greatest practical creature effects ever filmed.

But an underrated aspect of "Jaws" is how Spielberg made a beautifully textured hangout movie between the action, uniting three singular character actors — Roy Scheider, Robert Shaw, and Richard Dreyfuss — into an adventure-horror film that slows down just enough to let us soak in the warmth of three men at sea before snapping back into gripping suspense. "Jaws" is a perfect genre picture, and the thoughtful blockbuster it introduced is one we rarely see now.

North by Northwest

For "North by Northwest", Alfred Hitchcock abandoned the dense symbolism of "Vertigo". Instead, he dropped Golden Age icon Cary Grant into a globe-trotting espionage flick of dive-bombing planes, sultry train rides, and danger atop Mount Rushmore — a scene that even stirred some government controversy.

Building on his love of mistaken identity plots, Hitchcock and screenwriter Ernest Lehman crafted a set-piece-heavy spectacle often seen as a precursor to modern action films. It's a deliberate snare for those who think of Hitchcock as an over-serious pulp artisan — here, he's having a blast, and the result is a perfectly paced crowd-pleaser, tossed off with deceptive ease.

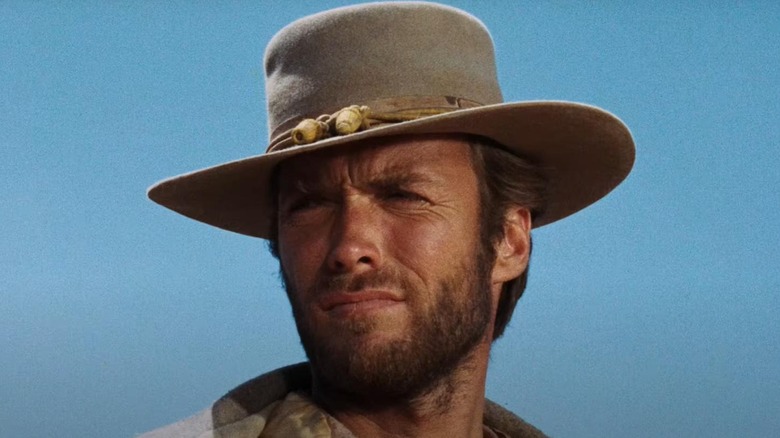

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

The conclusion of Sergio Leone's "Dollars Trilogy," "The Good, the Bad and the Ugly" is a defining Spaghetti Western, imagining the American West as a hazy dreamscape of beauty and bloodshed. Mostly shot in Spain, the contrast between its European production and the Civil War-era setting creates a kind of poetic alienation, revealing deeper fractures in American mythmaking.

Even so, Leone and his expert cast — Clint Eastwood, Eli Wallach, and Lee Van Cleef — deliver iconic sequences you've likely absorbed by cultural osmosis. But in full context, they still hit like a train. With sweeping cinematography by Tonino Delli Colli, a legendary Ennio Morricone score, and bravura set-pieces including a practical bridge explosion, "The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly" is a classic that really is just that good.

12 Angry Men

Sidney Lumet's dialogue-driven classic is one of the great masterpieces of surmounting a moral crisis, as twelve white jurors are packed into a stuffy room on a sweltering summer day to settle the fate of a young Puerto Rican defendant charged with murder. As a legal drama, "12 Angry Men" is as robust as they come; as an example of the power filmmaking has to make a group of people talking in a room as exciting as any action movie, it's almost unbelievable.

Lumet, cinematographer Boris Kaufman, and screenwriter Reginald Rose turn what in other hands could feel like a superficial school lecture into a marvel of narrative economy and constructive use of limited space, so gripping is it in drilling deep into the psychology and prejudices of its marvelous ensemble, centered on Henry Fonda's dissenting everyman who helps usher his resolute peers towards justice. The film feels starry-eyed in today's political climate, but its infectious idealism speaks to the potency of the material.

The Night of the Hunter

Charles Laughton's lone foray into directing stands as perhaps the most remarkable single-film legacy in cinema. "The Night of the Hunter," based on Davis Grubb's 1953 novel of the same name, received mixed reviews and poor box office returns upon release, which were responsible for Laughton never again helming a feature film from behind the camera, but the moody, gothic stylings of this Deep South quasi-horror crime picture demonstrate a filmmaker with a rich understanding of his cinematic progenitors.

Laughton's employment of German Expressionist techniques makes for a film that feels both out of time and ahead of the curve of other standard American dramas from the '50s, envisioning familiar facets of the country as vicious opportunities for avarice and violence. He finds a perfect vehicle for this unease in Robert Mitchum, delivering an electrifyingly disconcerting performance as the preacher-posing serial killer Harry Powell — one of the greatest villains in movie history — out to nab a stashed-away $10,000 by any means necessary. "The Night of the Hunter" reveals a certain wickedness tucked away in the creases of America's amiable exteriors and religious devotion, and it does so with an enduring, stylized dread.

The Third Man

One of the best noirs of all time is also one of the most genius uses of the all-encompassing presence of Orson Welles, whose relatively brief on-screen appearance causes the magnitude of his company to swell like the strongest of tidal waves. But for the most of the film, his character, Harry Lime, acts as a specter hovering over Joseph Cotton's Holly Martins, a pulp writer who arrives in Austria to visit Lime only to find that he's died in an accident — but something suspicious is afoot when Martins learns of the existence of a "third man" at the scene of the incident.

Martins is sent on a spiraling pursuit for the truth across Vienna, with English director Carol Reed materializing the turmoil and confusion of his protagonist via the stark black-and-white framing of Robert Krasker's camera, which turns the streets of the city into a frenzied labyrinth of deceit and fatalist consequences. Also featuring one of the best final shots of all time, "The Third Man" is a model example of converting all the base components that make a great film into one amazing, unifying whole.

Night of the Living Dead

The grandfather of the zombie genre as we know it today is notable not only for its pioneering approach to horror — with its uncharacteristically graphic scenes of blood and gore — but also as a landmark of independent, DIY filmmaking and political cinema. Zombie movie maestro George A. Romero kicked off his "Living Dead" series with this cult-classic-turned-genre-essential, which traps a group of everyday Americans in a rural shack as they fend off encroaching "ghouls" afflicted with a pernicious sickness and a craving for human flesh.

Made during the chaotic later years of the Vietnam War and in the thick of the Civil Rights Movement, Romero envisions citizens forced to confront a sickness of both mind and body plaguing the nation. Central to this radical dissection of the era is the casting of Duane Jones, a Black man whose ultimate fate reveals a grisly truth about the country's social condition, and offers a stark commentary on who violence-prone Americans believe they need protection from. "Night of the Living Dead" was mired in controversy and landed like a bomb on an unsuspecting audience, serving as both a mirror to a sick society and a relentlessly bleak horror film, complete with the grim deaths of major characters (including children) and a deliberately desolate, unsatisfying ending.

Taxi Driver

"Taxi Driver" is a film so discerning in its upsetting nature that it seems out of place for it to be constantly lumped in with other college-dorm-room-poster "bro" cinema. It's a severely grim portrait of America's prejudices and malice distilled into one lone, radicalized psychopath: Travis Bickle, an unwell Vietnam War veteran played with an initial disarming charm and naivety by Robert De Niro, which slowly morphs into the persona of a sociopathic lunatic.

Decades before any discourse about the "male loneliness epidemic," director Martin Scorsese and screenwriter Paul Schrader made a film about a man whose isolation is self-imposed, a result of a specific brand of male entitlement and an all-encompassing sense of bigotry. His eventual turn toward some kind of self-perceived vigilante justice in an ultra-violent ending is just a reflection of long-stewing violent tendencies; his simmering rage toward the citizens populating the streets of New York is the outcome of a man who feels like he was owed a life not afforded to him. Scorsese and Schrader perfectly depict a particularly toxic strain of male malaise in this crucial analysis of one deranged character.

Bringing Up Baby

In an interview with Peter Bogdanovich, director Howard Hawks once spoke about a self-perceived misstep regarding his manic 1938 comedy "Bringing Up Baby": "There were no normal people in it. Everyone you met was a screwball... I think it would have done better at the box office if there had been a few sane folks in it." He's potentially right about the box office, but this is the very reason that "Bringing Up Baby" endures as so effortlessly, resoundingly funny today.

With the irreconcilable pairing of its leads, Cary Grant and Katherine Hepburn, "Bringing Up Baby" is a screwball romantic comedy in the most classical sense, and is further escalated by its nutty digressions, including the eventual leopard that enters the plot and gives the film its name. It's comedy amplified to pure Looney Tunes levels of cartoon anarchy; some may even find its incessant nature of havoc and brash personalities taxing. If you're like me, you'll find 100 minutes of belly laughs.

The Apartment

Regular collaborators Billy Wilder and I.A.L. Diamond's follow-up to their Marilyn Monroe-starring hit "Some Like It Hot" is surprising in how it utilizes an ostensibly madcap premise to close in on stirring pathos. Jack Lemmon also returns from that previous film for "The Apartment," this time as CC Baxter, a small, anonymous cog in the large corporate machine of an insurance company, who receives preferred treatment from some of his higher-ups as he runs a side-gig loaning out his apartment for them to take their mistresses to, a premise that Jack Lemmon saw as more controversial than "Some Like it Hot."

With elements of mistaken identity from Baxter's neighbors believing he's a playboy, to his scrambling to adjust his apartment-borrowing schedule for his superiors, there are traces of the more outwardly zany comedy this could have ended up as. But as Baxter becomes involved with the elevator girl Fran (Shirley MacLaine), who herself is involved with Baxter's unscrupulous boss Jeff Sheldrake (Fred MacMurray), "The Apartment" begins to define itself in a more tragicomic register, with an ample understanding of how to offset the buried misery of its characters with an amicable sense of comedy. It's well-suited for fans of "It's A Wonderful Life," with its elements of melodrama and throughline of a man learning to unfetter himself from the authority of corporate power structures set at Christmas time. More than anything else, it's just a treat to watch. Y'know... movie-wise.

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre

For a horror film whose villain would go on to typically be lumped in with your other standard slasher boogeymen like Michael Meyers or Jason Vorhees, it's always a shock to the system to watch "The Texas Chain Saw Massacre" and see how closely it veers to being something completely avant-garde, totally separated from almost any major horror release before or since.

Sure, Leatherface may now be the face of a franchise built on a standard practice of IP-mining, leading watered-down remakes and used to prop up an always-online co-op video game, but when Tobe Hooper and his ragtag team of Texas DIY filmmakers first gave him life, it was in a movie full of an almost unrecognizable aura of disquiet and terror.

In "The Texas Chain Saw Massacre," the kills are quick and feral, the tone is grungy and chaotic, and the story is abrupt and merciless. Hooper made a movie about the decay of American idealism in the '70s that spoke directly to the heart of a nation's fear, anger, and distrust within savage suggestions of brutality that were now familiar to a populace that had spent years watching a needless war waged overseas in Vietnam and were now privy to Charles Manson-type evils. In its concentrated dose of political and visceral backcountry frenzy, "The Texas Chain Saw Massacre" is one of the most important horror movies ever.

Moonlight

Barry Jenkins' breakthrough 2016 film that divides the coming-of-age of a queer man into three distinct chapters of his life was nothing short of stunning upon its initial release, a true calling card for an essential new voice in cinema if there ever was one. Nearly 10 years on, "Moonlight" is still breathtaking, perhaps even more so for how time has proven Jenkins' intimate, sensitive vision to be wholly singular. In his delicate, naturalistic drama defined by small character moments of knowing glances and meaningful gestures, Jenkins builds a critique of contemporary masculinity directly into the filmmaking that coincides with the development of his characters, suggesting that a better world where we curb the cyclical repression of men's emotions can exist, and it would result in a more caring, empathetic world for all.

James Laxton's shallow-focus framing of his subjects is luminous and recalls the films of Wong Kar-Wai, allowing the audience to easily locate the pained history and desperate need for connection felt by the principal cast, who all turn in exceptional performances, especially Trevante Rhodes and André Holland. With "Moonlight," Jenkins proved himself as a crucial filmmaker of his generation.

Memories of Murder

Before Bong Joon-Ho made waves as the director to tie up Oscar records with "Parasite," which also was the first non-English language film to win Best Picture, and even before he was widely known to cult film audiences as a constructor of fun genre escapades like "The Host" and "Snowpiercer," he made one of the best police procedurals of all time with "Memories of Murder."

Led by regular Bong collaborator Song Kang-ho, "Memories of Murder" follows two South Korean detectives as they attempt to solve a murder case — a bog-standard, no-frills premise when talking about procedurals. However, Bong's adept filmmaking sensibilities set this apart, riding the line between the pulp thrills of its genre template and the melancholy nature of his protagonists, whose obsession with their case gives the narrative turns a particularly sobering sense of malaise and deliberate discontentment. As far as kinetic narratives underlined by disillusioned characters and indifferent societal structures, it's most easily compared to David Fincher's "Zodiac," and Bong beats that movie to the punch by four years.

Malcom X

"Malcom X" was a movie decades it the making that almost never came to exist: it faced enormous controversy before production; it changed directorial hands from Norman Jewison to Spike Lee after public backlash; Lee had to contribute a chunk of his own salary to finish filming; and then, the project got shut down in post-production for running over budget before being saved by a handful of financial contributors including Oprah Winfrey, Michael Jordan, Prince, and more.

With that in mind, more than just a movie that shouldn't exist, it's a film whose difficulties meant that it could have easily been an extraordinary 3-hour boondoggle. But "Malcolm X" is an essential biographical examination, with Lee and Denzel Washington at the height of their respective powers, conveying the grand, mythic scope of Malcom X's life by concentrating on the intricacies of his humanity, intellectualism, and collective pieces of activism that comprised his indomitable fight. It is a plain text for understanding the fundamental struggle that rests in the soul of a nation that loves to romanticize its sense of democracy and brush over its horrible legacy and, more simply than that, it is simply a pitch-perfect approach to the often tedious genre of the life-spanning biopic.

Jackie Brown

In a filmography full of movies that could reasonably be considered a director's best, "Jackie Brown" has to be Quentin Tarantino's most consistently underestimated. In his adaptation of the novel "Rum Punch" by Elmore Leonard, Tarantino tones down some of his more overbearing tendencies as both a writer and filmmaker, delivering a crime movie that operates as a loving homage to '70s blaxploitation, while still operating in the realm of his subversive sense of pop filmmaking owed to an obsessive love of cult and genre filmmaking that consistently bleeds into his work.

The 1997 flick feels separated from his other projects — it's the only movie not completely based on his own idea. Tarantino apparently doesn't even consider "Jackie Brown" part of his cinematic universe. For an auteur whose films are usually defined by a particularly caustic strain of post-modernism, perhaps the most surprising facet of "Jackie Brown" is the earnest, romantic quality imbued into its story and characters, with Tarantino delivering a certain level of emotional sincerity he wouldn't quite locate again until "Once Upon a Time... In Hollywood." "Jackie Brown" is still about Tarantino's love for pulp stories, but it's one that smoothly nestles itself right within the body of the director's influences, as opposed to merely existing as an inevitable product of those films' impact.