The Story Behind The Best Episode Of The Simpsons, A Conan O'Brien Masterpiece

In the 1993 "The Simpsons" episode "Marge vs. the Monorail," the corrupt nuclear power plant owner Mr. Burns (Harry Shearer) is busted by the EPA for stuffing glowing toxic waste into trees at the local park (the trees sprout tentacles and the squirrels gain eyeball lasers). As punishment, Mr. Burns is fined $3 million, which he happens to have in his wallet. Springfield, suddenly flush with cash, has a town meeting debating what to spend it on. Marge Simpson (Julie Kavner) proposes that they use the money to fix up pothole-strewn Main Street, but a mysterious flim-flam man named Lyle Lanley (Phil Hartman) interrupts her. Using a broad smile and heaps of smarmy charm — and a "Music Man"-style musical number — Lanley convinces Springfield to spend the money on a monorail that he will build himself.

Clearly, Lanley is a con man who sells shoddy monorails to unsuspecting cities and then skips town before his low-rent transportation fails. In a hilarious twist, Lanley's old targets fall into dystopian ruin. "Marge vs. the Monorail" is hilarious, odd, and came from a time when "The Simpsons" was firing on all cylinders. /Film recently declared it to be the best "Simpsons" episode of them all, which is no small feat, given that the series is about to enter its 2,145th season.

"Marge vs. the Monorail" was written by Conan O'Brien, then a staff writer on the series, and directed by longtime animation veteran Rich Moore. In 2020, Vice interviewed the makers of "Marge vs. the Monorail" to get the full story of its making, and where the initial idea came from.

Inception

Where did this weird idea come from? The idea of a con man bilking Springfield out of millions of dollars seems like a fine idea for a "Simpsons" story, but why a monorail? "Marge vs. the Monorail" was also clearly inspired by "The Music Man." Was Conan O'Brien a fan, or was he merely fond of the structure? According to showrunner Mike Reiss, O'Brien was still something of a "new kid" on the show, and the entire episode was his idea. Reiss and co-showrunner Al Jean heard O'Brien's pitch (at a special writers' retreat) but were concerned that show creator Matt Groening and executive producer James L. Brooks wouldn't like it. They were wrong. Brooks loved it. Indeed, Reiss recalls that O'Brien successfully pitched three script ideas during the writer's retreat.

Story editor Josh Weinstein recalled O'Brien as being energetic and "up" all the time. "Working with Conan was like watching a ten-hour episode of his show, every day, in the writers' room," he said. "All the other writers are hilarious, but most of them are quiet and thoughtful, whereas Conan's just out there."

As for the "Music Man" thing, that was all O'Brien. Producer Jeff Martin, in the Vice oral history, noted that O'Brien turned in the lyrics and his was his job to make it musical:

"Every single word of the monorail song was unchanged from Conan's first draft, which is impressive. My niche on the show in those days was to actually write the tunes to the songs. I wrote a bunch of songs, so I was assigned to set the monorail song to music. It's sort of like, 'Bum, bum, bum, bum. I think I'm done!' It's barely a song. It's just sort of a rhythm and 'Monorail! Monorail! Monorail!'"

Mono– D'oh!

The Simpsons gets surreal

Compare the fourth season of "The Simpsons" to the first, and one will notice a definite change in tone. "The Simpsons" started as a send-up of the all-American sitcom. Homer (Dan Castellaneta) was initially a below-average blue-collar boob who was deathly afraid that his family was also below average. Homer was often preoccupied with traditional suburban traditions like saying grace at dinner, and enjoying milkshakes as a family. As the years passed, Homer transformed into a half-mad, child-brained weirdo who only dimly perceived the world around him. Springfield transformed from an "average all-American town" into a filthy, tilted universe, perhaps just next door to the Twilight Zone.

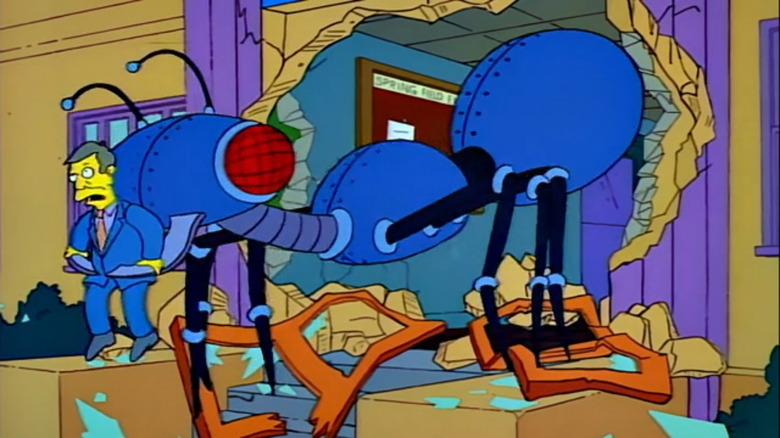

"Marge vs. the Monorail" features a brief fantasy sequence wherein Principal Skinner (Shearer) is cut in half by giant mechanical ants. That sort of scene wouldn't have appeared in the show's first season. At the end of the episode, special guest star Leonard Nimoy openly broke the laws of physics, a notable first for the series. Reiss recalled the shift, saying:

"The show was slowly drifting into surrealism. At the end of that episode, when Leonard Nimoy beams out of there like on 'Star Trek,' I remember Jeff Martin said he was thinking, 'Alright, I guess we're doing this now. "The Simpsons" has decided it can break physical laws.' It wasn't a vision we had for the show or anything like that, Al [Jean] and I were just trying to get laughs. The show had to get a little bigger and weirder all the time for it to do that."

They followed their hearts, and their hearts were leading the "Simpsons" down a very, very weird path.

The inimitable Phil Hartman

According to everyone interviewed for the Vice piece, Phil Hartman was a true professional. He nailed every line on his first read and was a delight to work with. Some of the showrunners noted that Hartman was always upbeat, usually coming across as one of his characters, even when he wasn't in the recording booth. The animators didn't want to design Lyle Lanley to look too much like Hartman, and clearly took physical cues from Robert Preston's character in "The Music Man." By the time "Marge vs. the Monorail" aired, however, Hartman had already appeared on "The Simpsons" 14 times, playing the shyster lawyer Lionel Hutz, the blowhard actor Troy McClure, and a few other ancillary characters.

As the article noted, "Marge vs. the Monorail" was one of the earlier instances of Springfield emerging as a character unto itself. There are hundreds of characters on the series, but when you get them all in the same room, Springfield emerges as an ignorant, easily manipulated mass. Jeff Martin noted:

"Mindless groupthink is a recurrent theme on 'The Simpsons,' and I think the monorail episode is the best — and certainly my favorite — example of Springfield mob mentality. Watching the episode, I decided to go ahead and time it. From Lanley whistling in the back of the auditorium to the entire town marching on the town hall steps singing 'Monorail!' is a little less than two minutes. I think it took Harold Hill at least four minutes to whip up River City."

We got trouble, my friends.

Disaster!

At the end of "Marge vs. the Monorail," the monorail breaks down on its maiden voyage, causing its engines to jump into overdrive and its brakes to fail. Homer, the driver, has to reach out of the window, pull a metal "M" off the monorail's exterior ("M" for monorail), and use it as an anchor to slow the vehicle. The dragging anchor cuts through the oldest tree in Springfield and does a lot of other damage besides.

Ultimately, the reason many attach themselves to "Marge vs. the Monorail," at least according to Rich Moore, is how cinematic it is. There are a lot of new settings and scenarios never seen on "The Simpsons" before, and Moore compared it to a 1970s Irwin Allen-style disaster movie. That, he felt, helped elevate the episode. Moore said that he had to assemble shots on the fly, and felt lucky that everything came together as well as it did:

"It was all done with coverage. It was scenes out of order. It was really just guesswork. 'I'm going to need this kind of shot — I'm going to need it going away from the camera, I'm going to need it coming towards the camera, dragging this giant 'M' around as an anchor, and it bouncing around.' Since there wasn't a whole lot of time up front, before it was animated, it was just like, 'Okay, I'm going to have to let go a little bit and trust that if I create this group of shots, we're going to be able to construct something worthwhile at the back end.'"

After this episode, "The Simpsons" became stranger and stranger, and remained on a hot streak for many years. A common complaint about "The Simpsons" is that "it hasn't been good since season [blank]." Everyone can agree, however, that season 4 was one of the better times for the series.