Ten Days Before The Twilight Zone Premiered, Mike Wallace Asked Rod Serling A Question That Aged Badly

Nobody can predict the future, but sometimes our predictions are way, way off. Back in 1946, 20th Century Fox studio executive and Oscar-winning film producer Daryl F. Zanuck said television was a fad that would run its course in six months. "People," he argued, "will soon get tired of staring at a plywood box every night."

Zanuck was wrong. Television not only changed the industry, it changed the world. And over time, this medium that seemed like a flash in the pan developed its own identity, not just as an industry but as an art form. Brilliant writers like Paddy Chayefsky and Rod Serling helped push the stories told on television into exciting and challenging directions, setting the stage for ambitious standalone and serialized entertainments that wowed audiences and made a genuine impact.

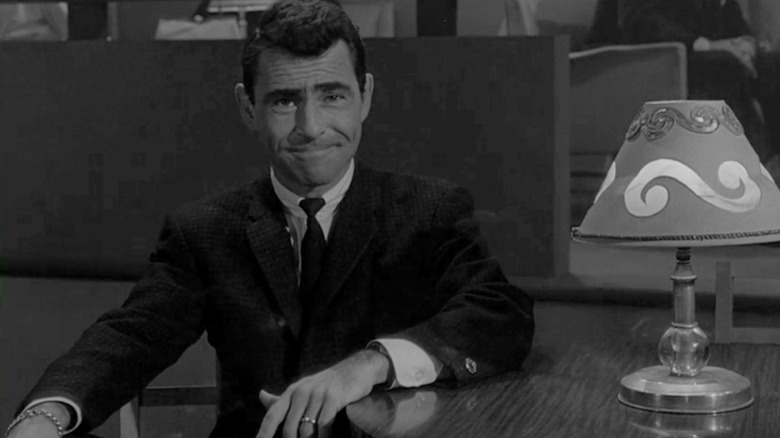

One television series that made its mark and remains influential and iconic today is Rod Serling's "The Twilight Zone," a sci-fi/fantasy anthology series featuring tales of irony and morality that gave popular culture some of its most enduring references and helped establish sci-fi/fantasy in the mainstream as a serious artistic enterprise. "The Twilight Zone" is arguably one of the most important accomplishments in the history of television.

And yet, just ten days before the premiere of the very first episode (sort of), newsman Mike Wallace interviewed Rod Serling and asked him a question that he never would have asked if he could have predicted the future...

'You've given up on writing anything important'

We have to set the stage here, because Mike Wallace's question came at an interesting time in Rod Serling's career. He had made his name writing hard-hitting, serious teleplays like "Patterns," about the intersecting evils of ageism and capitalism, and "Requiem for a Heavyweight," about a boxer with brain damage struggling to rebuild his life. He also wrote scripts like "A Town Has Turned to Dust," originally an allegory for the lynching of Emmett Till, until network sponsors demanded crowd-pleasing changes that undermined Serling's artistic vision.

The episode of "The Mike Wallace Interview" featuring Serling had already delved into his comically difficult tussles with sponsors, who demanded bizarre changes to his many screenplays and made it difficult to tell controversial stories. "The Twilight Zone," Serling himself argued, was designed in such a way that sponsors would have little to complain about. "We're dealing with a half-hour show, which cannot probe like a ninety [minute show], which doesn't use scripts as vehicles for social criticism. These are strictly for entertainment."

By this point, Serling was well into production on the first season of "The Twilight Zone," and either he was fooling himself — which seems highly unlikely — or he knew he was about to get away with something. They were likely already working on "The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street," as damning an indictment of "Red Scare" McCarthyism as any ever filmed. Future episodes of "The Twilight Zone" would directly warn the audience of the rise of American white supremacist fascism, the painful scars left over from the Holocaust, and the dangers of capitalism replacing workers through automation.

Still, at the time, nobody had seen a frame, so Mike Wallace could perhaps be forgiven for asking, "For the time being and for the foreseeable future, you've given up on writing anything important for television, right?"

'A tired non-conformist'

It's not a question that has aged terribly well, but to be fair, even Serling seemed to agree with Mike Wallace at the time.

"Well, again this is a semantic thing," Serling said. "'Important for television.' I don't know. If by 'important' you mean I'm not going to try to delve into current social problems dramatically, you're quite right. I'm not." [Editor's note: He did.]

But as the interview continues, it sounds less like Serling was trying to take a break from writing quality television and more like working with the milieu of sci-fi/fantasy simply made sponsors easier to work with.

"Somebody asked me the other day if this means that I'm going to be a meek conformist. My answer is no, I'm just acting the role of a tired non-conformist, and I don't want to fight anymore," Serling said. "I don't want to have to battle sponsors and agencies. I don't want to have to push for something I want and have to settle for second best. I don't want to have to compromise all the time, which is, in essence, what the television writer does if he wants to put on controversial things."

The frustration that emanates from Rod Serling in "The Mike Wallace Interview," as calm and collected as he sounds, is palpable. Serling believed that television could be a powerful art form, except corporate interests were holding it back:

"I think it's criminal that we're not permitted to make dramatic note of social evils as they exist, of controversial themes as they are inherent in our society. I think it's ridiculous that drama, which by its very nature should make a comment on those things that affect our daily lives, is in the position, at least in terms of television drama, of not being able to take this stand. But these are the facts of life."

'This I have to reject'

It's important to remember that in its infancy, television wasn't a well-respected art form. The inherent commercialism of the medium seemed at odds with a genuine artistic spirit. Wallace even quoted Herb Brodkin, a prominent TV producer, who said, "Rod is either going to stay commercial or become a discerning artist, but not both."

Serling remembered the quote. "I didn't understand it at the time. I failed to achieve any degree of understanding in the ensuing years, which are three in number," Serling explained. "I presume Herb means that inherently, you cannot be commercial and artistic, you cannot be commercial and quality, you cannot be commercial concurrent with having a preoccupation with the level of storytelling that you want to achieve. And this I have to reject."

"I don't think calling something commercial tags it with a kind of odious suggestion that it stinks, that it's something raunchy to be ashamed of," Serling added. "If you say commercial means to be publicly acceptable, what's wrong with that?"

Rod Serling was an early proponent of the now-popular idea that new media could be an art form and "pop art" could also be meaningful art. Over the course of his five seasons with "The Twilight Zone," Serling effectively proved that premise.

Wallace may not have predicted the future of Serling's writing career, but in his final thoughts, Serling did say something about television that has, thanks in no small part to his work, proven accurate:

"Some television's wonderful. Some television is exciting and promising and has vast potential. Some television is mediocre and bad. But I think it has promise, Mike. I think this can conceivably be a real art form and I stick with it for the reasons I said, and because I think it can only improve, and improve tremendously, and I think aims toward that."