The Twilight Zone Parodied Studio Notes By Having Shakespeare Punch Burt Reynolds

There's a piece of advice that every writer gets at some point in their career, and it goes like this: "Write what you know."

It's not bad advice if you don't take it too literally. "Write what you know" doesn't mean that you should only write about your own autobiographical experiences, it means that when you do write from experience you'll probably be able to write more truthfully, more meaningfully, and in more detail than if you had to make it all up from scratch. Even if you write about strange new planets filled with creatures totally unlike anything found on Earth, you're probably better off finding an angle that speaks somehow to your personal interests, your beliefs, or your memories.

The irony of course is that as writers keep on writing, eventually "what they know" the most about is being a writer. You may have noticed that a whole heck of a lot of Stephen King characters are novelists. And you may have noticed that Hollywood types love to make movies and TV shows about working in Hollywood.

"The Twilight Zone" creator Rod Serling was no exception to this rule, so although he wrote a lot of different stories about a lot of topics that spoke to him in various ways, he wasn't above writing the occasional tale about why the entertainment industry is a terrible place. Sometimes it's a story about how Hollywood Westerns are insipid and irresponsible. And sometimes it's a story about how Hollywood studios would ruin the works of William Shakespeare if he were alive today.

The teleplay is the thing

Let's travel back in time to the fourth season of "The Twilight Zone," in which the episodes were stretched to an hour long. It was a major misstep for the series that left the majority of the season's installments awkwardly padded. But there are a couple of exceptions to this rule, like the disturbingly prescient white supremacist tale "He's Alive," starring a young Dennis Hopper, and — more to the point — the playfully self-aware Hollywood farce "The Bard," in which William Shakespeare becomes a literal ghostwriter.

"The Bard" stars Jack Weston ("Cactus Flower") as Julius Moomer, a hack screenwriter whose enthusiasm can't compensate for his extreme lack of talent. When we meet Moomer he's rattling off script ideas to his long-suffering agent, and mostly they're terrible and/or seriously underdeveloped. He's got one idea about a woman who doesn't know she's married to a zombie, and another idea for a woman who falls in love with a robot she invented. (Although admittedly one of his ideas turned out to be a good one: "Boy Meets Girl," an anthology series about a different meet cute every single week, has a premise very similar to the 1970s series "Love, American Style," which later spun off into the legendary hit sitcom "Happy Days.")

To get Moomer out of his office his agent agrees to give him a crack at a new TV pilot about black magic. Moomer doesn't know anything about it, so he gets himself a spell book and tries to conjure up a spirit, and he accidentally summons the ghost of William Shakespeare, played by John Williams (the actor from "Dial M for Murder" and "Sabrina," not the composer). Shakespeare is here to do Moomer's bidding, and so Moomer puts him to work, and then he simply puts his own name on The Bard's brilliant script.

The fool doth think he is wise

The network is very happy with Moomer's latest masterpiece, a teleplay called "The Tragic Cycle," and immediately sets a meeting with the show's sponsor, a food corporation. And here we quickly find out what Rod Serling is really getting at. The sponsors have barely had Shakespeare's/Moomer's screenplay for a minute before they start making arbitrary changes. A line about how an onion makes you cry is swiftly changed to a turnip, even though that doesn't make any sense, because unlike onions (?), "everybody knows about turnips."

Moomer, who wants to be a successful screenwriter and doesn't care about being a good one, quickly rolls over for the network and makes every alteration they ask for. But when Shakespeare decides to visit the set and see how his script is coming along he's in for a rude awakening. Shakespeare discovers that the sponsors have changed everything about his story, removing the tragic climax in which the protagonist ends her own life and replacing it with a scene where she "runs away with this bass fiddler from Artie Shaw's Gramercy Five," and switching out her grieving mother with "the gardener's wife," a new character who "did time for embezzlement."

A poor player that struts and frets

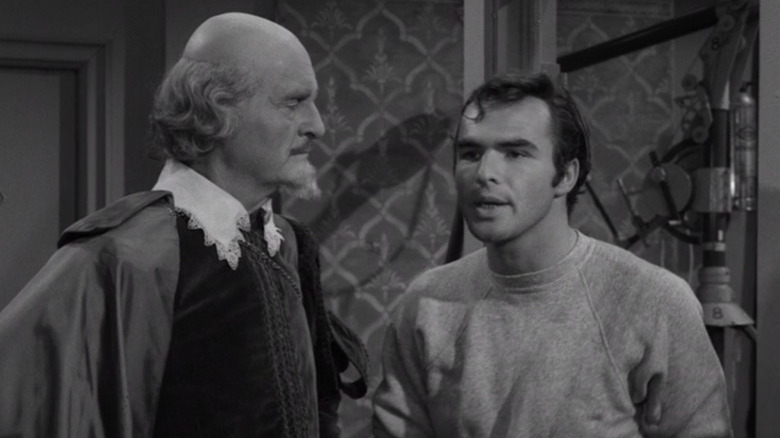

Adding insult to Shakespeare's injury is the teleplay's star, Rocky Rhodes, a stuck-up Method actor who needs a detailed explanation about why his character would be motivated to open a door before he'll even rehearse a scene. Rhodes is famous for his performance in "A Streetcar Named Desire," and in case that wasn't a big enough hint for you, he's also played by a young Burt Reynolds, who looks a lot like a young Marlon Brando and is doing a nearly perfect vocal imitation of the "Wild One" star to boot.

Well, that's the last straw for Shakespeare. Infuriated with the whole modern studio system, Shakespeare punches Marlon Brando — er, "Rocky Rhodes" — so hard he falls head over heels into a pile of chairs. Moomer tries to tell Shakespeare that's just the way Hollywood works, and Shakespeare leaves him with a withering speech:

"And you, Julius Moomer, foolish mortal, you could have covered yourself with a cloak of immortality. To you, Julius Moomer, who has succumbed to the rankest compound of villainous smell that ever offended nostril; to you, Julius Moomer ... lots of luck."

So yeah, Rod Serling had some opinions about studio notes. Have you noticed the subtle allegory here? Have you realized that he's writing from personal experience?

Fight to the last gasp

There have been studio notes as long as there have been studios. Movies and television are expensive artistic mediums, so the people who foot the bill want to be confident they'll make their money back, preferably with a profit. It's not surprising when they try to steer productions into the mainstream, shirking bold ideas in favor of clichés. Naturally they'd want to make the sponsors of their TV shows, without whom they could not afford to make any shows at all, as happy as possible.

Behind the scenes there's almost always a battle raging between artists trying to make the best art and executives trying to make the safest investment. Not all studio notes are bad — in the original ending of "Clerks" Dante was anticlimactically murdered in a liquor store robbery, and cutting it was a good idea — but some are ridiculous, and Serling had to deal with a lot of those.

Take the episode of "The Twilight Zone" where they weren't allowed to say British people drink tea, because their sponsor made coffee. Or worse, the time when Serling wrote an allegory about the tragic murder of Emmett Till that was changed, piece by piece, until it no longer had any relation to reality. Or the other time Serling wrote an allegory about the tragic murder of Emmett Till that was changed, piece by piece, until it no longer had any relation to reality. That literally happened twice, to the teleplays "Noon on Doomsday" and "A Town Has Turned to Dust."

"By the time 'A Town Has Turned to Dust' went before the cameras," Rod Serling said in The Twilight Zone Companion, "my script had turned to dust." Bad studio notes, Serling argues in "The Bard," don't just ruin his own scripts, they would literally ruin the greatest writing ever written, by the greatest writer who ever lived.