The Pilot Episode Of The Twilight Zone Wasn't An Episode Of The Twilight Zone

In the world of television, first impressions are everything. A great pilot episode is a promise to the audience, telling them what the show is about and how it will go about it, in the hopes that people will be so impressed that they'll tune in every week. If you don't grab them early, you might lose them altogether.

Case in point: If you watch the first episode of Rod Serling's "The Twilight Zone" you'll find that it is one of the most striking TV series debuts in history. The disturbing standalone tale "Where Is Everybody?" stars Earl Holliman ("Police Woman") as a man who finds himself in a town without any people in it. It's completely deserted from top to bottom, or is it? He keeps coming across signs that people were here, and he only just missed them. Trapped in a completely open world, alone in a space made for thousands of people, taunted by a mysterious unseen influence, "Where Is Everybody?" is an unforgettable nightmare that set the stage for the future of the anthology series, which would produce various tales of the strange and the fantastic across five acclaimed seasons.

But the funny thing about the pilot episode of "The Twilight Zone" is that, technically, it wasn't the pilot episode at all. Rod Serling sold the show based not on the quality of "Where Is Everybody?" but on the success of another weird tale that was produced for a completely different series.

The Westinghouse Desilu Playhouse

The producers and stars of the enormously popular sitcom "I Love Lucy," Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz, were a powerful force in the television industry. In addition to their own hit series, their production company Desilu was directly responsible for the creation of legendary shows like "Star Trek," "The Untouchables," and — you guessed it — "The Twilight Zone." But we'll get back to them.

Rod Serling was also a TV powerhouse in the late 1950s, thanks to hard-hitting, critically acclaimed, award-winning teleplays like "Patterns" and "Requiem for a Heavyweight." But Serling had become jaded with the process of producing teleplays, which often forced him to acquiesce to the bizarre demands of network sponsors, who demanded script changes that sometimes diminished the story's impact, or undermined the plot and themes entirely.

Since sponsors balked at serious issues that could turn off potential customers, or at least remind them that the real world is an unpleasant place, Serling moved away from conventional dramas and pulled out an old half-hour science-fiction script he had written in the early 1950s called "The Time Element." The teleplay originally aired on a series called "The Storm" on the Cincinnati station WKRC-TV, even though Serling had, at the time, been on staff at a rival network called WLW. Unfortunately for them, WLW didn't realize they had a huge talent on their hands, and what's more they had no interest in producing dramas. Instead they tried to enlist Serling to play a circus clown on one of their shows. (All that exists of that experiment is one lone photograph.)

Serling then expanded "The Time Element" into an hour-long teleplay and then sold it to CBS, a network that did not produce it. At least, not until producer Bert Granet came along.

Let's just say it was about time

Bert Granet was a producer at "Westinghouse Desilu Playhouse" — we said we'd get back to them! — and was working to improve the anthology series' image by enlisting attention-grabbing talent. Rod Serling fit the bill, so after Granet learned that one of the acclaimed writer's scripts was just sitting around gathering dust, he purchased it for $10,000 (that would be over $100,000 today, adjusted for inflation).

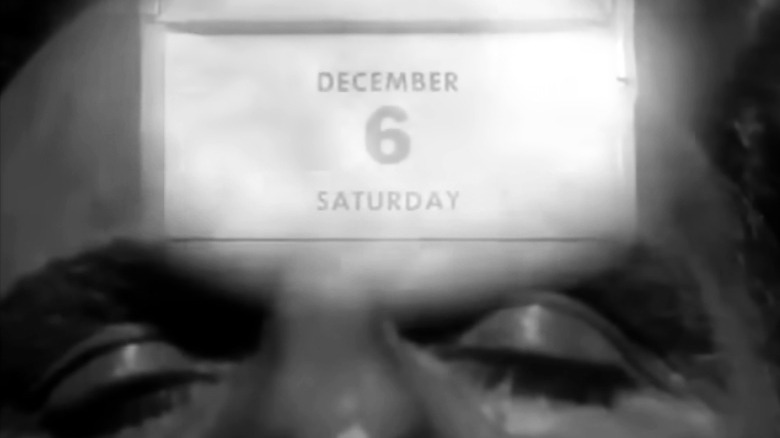

"The Time Element" is a striking high-concept story that starred Oscar-nominee William Bendix ("Wake Island") as Peter Jenson, a man in a psychiatrist's office describing a bizarre, recurring dream. Every night he dreams he goes back in time to Honolulu, Hawaii on December 6, 1941, and every night he tries to warn people of the impending attack on Pearl Harbor. But every night no one listens to him. His psychiatrist, played by Martin Balsam ("Psycho"), tries to convince Peter that time travel isn't real, but Peter has done his research. The people he dreamed of really existed, and they really died on December 7, 1941.

Serling's screenplay ended on an ambiguous note, suggesting that Peter Jenson either died in his latest journey back in time and rewrote himself out of existence, or that possibly his psychiatrist dreamed up the whole thing himself. Sponsors hated the idea of an open-ended story that left the audience scratching their heads. "They said if we did it I had to make a blood promise that I would never do that kind of a story again," Granet recalled in The Twilight Zone Companion.

But that's not how it played out. Not at all.

What a twist!

In a twist as ironic as anything found "The Twilight Zone," critics loved "The Time Element" and audiences flooded the network with letters about it. CBS realized Serling's idea for a weird anthology series had potential, and in the end "that kind of story" would be told every single week for many years on "The Twilight Zone."

But it wasn't a total victory: The sponsors still managed to worm their way into Serling's script for "The Time Element." One plot point in the original draft found Peter Jenson trying to warn the U.S. Army about the attack on Pearl Harbor, and to no avail. That wouldn't do for Westinghouse, according to The Twilight Zone Companion. The company had government contracts, so in the final version Peter tries — and fails — to alert the newspapers instead, with the semi-reasonable justification that the media might be able warn more people, more quickly.

The futility of Peter Jenson's plight comes across regardless, so although he is not officially a resident of Serling's "Twilight Zone," he still set the template for many of the protagonists that would follow in Serling's hit series. Hapless, ordinary individuals confronted with the strange and uncanny, who are completely incapable of convincing anyone else that their visions, their theories, and their torments are real. And in the end only the audience would really know for sure.

Except in the case of "The Time Element," because that broadcast ended with Desi Arnaz returning to the stage to announce that he thinks the whole story is just a dream, which really dampened the teleplay's dramatic ambiguity. Gee, thanks, Desi. Thanks a lot.