14 Mistakes You Never Noticed In The Twilight Zone

You're traveling through another dimension, a dimension not only of imagination but of cinematic imperfections. It is the middle ground between reality and illusion, between what is intended and what is captured on film. This is the dimension of mistakes and oversights. It is an area which we call "The Production Zone." In it, mirrors reflect mistakes, film equipment appears at the periphery of vision, continuity wavers, editing stumbles, and stock footage mismatches.

As you journey through this realm, you'll uncover imperfections often overlooked in the iconic series "The Twilight Zone." Known for thought-provoking tales, the series wasn't immune to production hiccups, gaffes, and glitches.

Question the facade of the extraordinary as we explore elusive mistakes — 14 in total — across beloved episodes in this "land of shadow and substance." Will you emerge unscathed from this journey into cinematic blunders? Or, like its characters, be forever changed by what you see? Answers await beyond the signpost up ahead, just beyond the threshold of imagination.

1. Fifth dimension meets fourth wall

In the realm of "The Twilight Zone," both the fifth dimension of imagination and the theatrical fourth wall push the boundaries of storytelling. The fifth dimension immerses you in the bizarre and supernatural, while the fourth wall in theater acknowledges your presence as an audience member. Intentional fourth-wall breaks include Serling's introductions, but unintentional, inadvertent mistakes reveal the artifice.

Take "The Four of Us Are Dying" (Season 1, Episode 13), where impressive photography showcases the lead character's face-shifting ability in a single, effects-free shot. In another scene, numerous neon signs hang, suggesting a city we don't see. Yet, a glaring flaw emerges when both the scenic backdrop's end and the soundstage wall and rafters become visible, abruptly breaking that fourth wall. Francis Ford Coppola could get away with such artifice in "One From the Heart" (1981), but here it sticks out like a sore thumb.

In the blink of an eye during "Stopover in a Quiet Town" (Season 5, Episode 30), an error appears as the camera whips to reveal Serling as the narrator. Sharp-eyed viewers can catch a glimpse of the kitchen set's right end just before the cut. Afterward, a stage light and crew members flash by like phantoms.

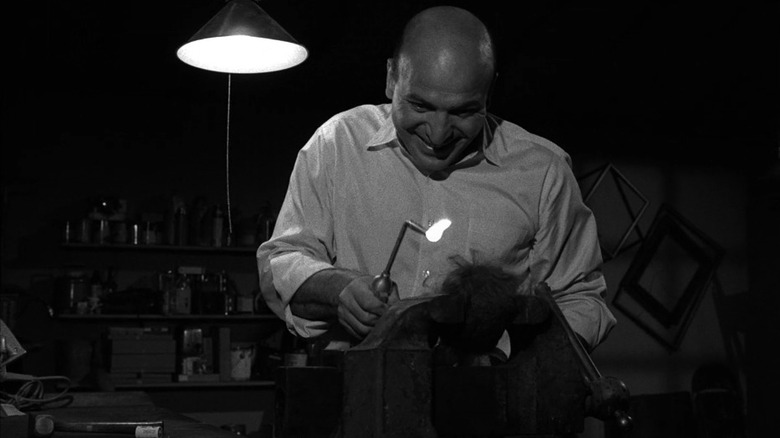

2. Telly Savalas flamed out

In "Living Doll" (Season 5, Episode3), a stepfather named Erich Streator (Telly Savalas) becomes furious when his new wife Annabelle (Mary La Roche) buys an expensive doll, "Talky Tina" (voice of June Foray), for his stepdaughter, Christie (Tracy Stratford). In response, the doll begins behaving eerily lifelike, issuing ominous threats targeting Erich. Despite his desperate attempts to get rid of the doll, it keeps reappearing, intensifying the psychological horror.

As the malevolent presence of the doll intensifies, Erich's frantic attempts to rid himself of this tormenting toy unfold. In a memorable sequence, he explores various methods to annihilate the sinister creation. When he gleefully hits on the idea of using a blowtorch, every time he brings the flames to Tina's face, the flame goes out. But watch Savalas' torch-holding hand. Notice the flame extinguishes not via magic or a special effect, but because his fingers release the trigger.

Was Erich unconsciously hindering himself from destroying the devilish doll? No. Talky Tina continues issuing threats even after his demise.

3. Frozen figure faux pas

People being frozen in place occurs in several "TZ" segments, representing dead bodies, mannequins, or people stuck in time. When moving characters needed to appear with them, freeze-framing was impossible. Actors and background players had to remain perfectly still, not shift their eyes, blink, sway, or breathe visibly. It's hard to do for more than a few seconds, especially when standing.

In "Elegy" (Season 1, Episode 20), director Douglas Heyes hid such minor movements by moving the camera, and this works well. However, any time the camera stops moving, the illusion is at risk of falling apart. But there's one scene where no amount of camera dolly can disguise the unfrozen background players. In a crowd scene celebrating the election of a mayor, there's a prolonged shot of the three astronauts, behind whom two of the "frozen" men blink repeatedly. The crew clearly didn't notice while filming. It's tough to miss in the finished episode, and film editor Joseph Gluck was probably tearing his hair out over it.

The septuagenarian couple in "The Trade-Ins" (Season 3, Episode 31), John and Marie Holt (Joseph Schildlkraut and Alma Platt), long for youthful vitality. A remarkable technological advance allows them to exchange their old bodies for young ones. But, as they browse the showroom of new body models, a pair of these inanimate showroom dummies abruptly shift positions a split second before vanishing from view.

4. Nightmarish footwear

"Nightmare at 20,000 Feet" (Season 5, Episode 3) is a spine-tingling journey into the depths of fear. While on a commercial flight, Robert Wilson (William Shatner) sees a disturbing creature (played by Nick Cravat) meddling with one of the plane's engines. Because Wilson has just been released from a sanitarium after experiencing a nervous breakdown, nobody believes him. The sheer isolation of the airplane's cabin amplifies the terror as the passenger grapples with his sanity and the safety of everyone aboard.

The gremlin-like creature is a menacing and bizarre entity with a hideous face. How effective the costume is to modern eyes viewing HD TVs depends on personal taste. (To me it looks like a soggy sheep with a grotesque mask.) But its biggest flaw is the soles of its feet. They're light-colored, clearly human-shoe-shaped, probably rubber to prevent the actor from slipping on the wet wing.

So, every time the "Nightmare" bears its soles, the illusion is diminished.

5. Small universe syndrome

While people often refer to "The Twilight Zone" as science fiction, it actually plays like more of a fantastic-tales affair. Hard science fiction it ain't, and no one fact-checked the science as De Forest Research did for "Star Trek." This is baldly apparent in episodes dealing with distances between heavenly bodies.

The "Third from the Sun" (Season 1, Episode 14), protagonists flee to a "small planet" 11 million miles from theirs. In the de rigueur "TZ" twist, that planet ends up being Earth. That's closer than either Venus or Mars. The iconic "To Serve Man," (Season 3, Episode 24) is contradictory about spatial distance. The human-hungry Kanamits (Richard Kiel) insist they originate "far beyond your knowledgeable universe." Two Earth morsels state it's 100 million miles away. Pick one, show.

In "Elegy," the astronauts determine the asteroid they've landed on is 655 million miles from Earth. That's closer than Saturn and farther than Jupiter, but said asteroid has two suns. And in "On Thursday We Leave for Home" (Season 4, Episode 16) two characters describe the colony world as "a billion miles" from Earth... also with two suns. A billion miles is further than Saturn and closer than Uranus. The nearest binary system to us, Alpha Centauri, is 40.2 trillion km away.

Why the confusion? Humans can imagine tens of thousands of things. But millions? Billions? Trillions? Our brains just can't even. Call it a journey into the imagination we can't make.

6. Instant wet to dry

Maintaining continuity in a scene can be exceptionally challenging, especially at the speed of 1960s TV series production. Add water to the equation and the continuity challenges multiply. Wet costumes, hair, and makeup must be consistent between takes. Tracking changes in water volume, and wetness level is essential to ensure a seamless visual flow in the final edit.

When two-bit thug Fred Renard (Steve Cochran) sits on a wet curb to put on a new pair of shoes in "What You Need" (Season 1, Episode 12) he gets a wet spot on his bottom. Moments later, he's hit by the car, and his trousers are dry. A neat trick to unwet yourself, right?

In "Mirror Image" (Season 1, Episode 21) when Millicent Barnes (Vera Miles) meets Paul Grinstead (Martin Milner), he wears a hat and raincoat. The hat remains wet, while the raincoat appears wet and dry when captured via during different camera angles. Closeups: wet. Two-shots: dry.

7. Vehicular vagueries via stock footage

In "The Hitch-Hiker" (Season 1, Episode 16), Nan Adams (Inger Stevens) drives a four-door, light-colored 1959 Mercury Montclair with four headlights. But in a single shot, when she serves to hit the titular hitch-hiker (Leonard Strong) we momentarily see a dark 1957 Ford Custom or Fairlane with two headlamps.

In "Nightmare at 20,000 Feet," it appears the in-flight shots of the plane are of a member of the Convair 240 family of twin-engine airliners. However, the gremlin does its dirty work on a wing with two propeller engines, which resembles that of a quad-engine Douglas DC-6 or -7.

The root of both inconsistencies? The use of stock footage. Doubtless, there was no appropriate shot of a matching airplane available for "Nightmare." Likewise, someone deemed a shot of a swerving car necessary. In both instances, stock footage filled the gap but created continuity mismatches.

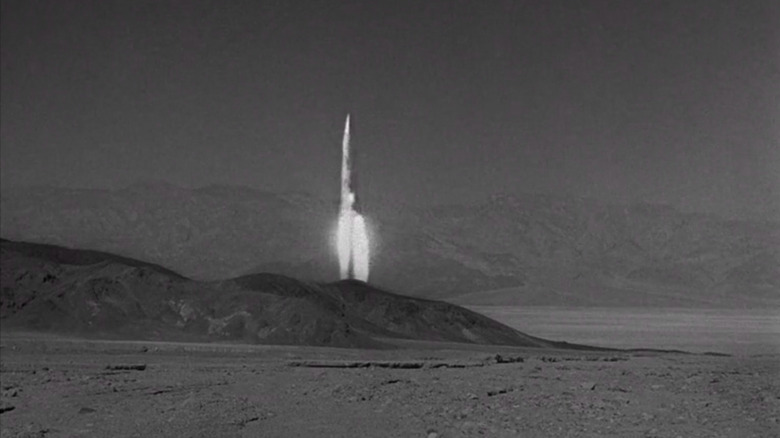

8. The wrong stuff

"The Right Stuff," a phrase popularized by Tom Wolfe's 1979 book and the subsequent film about America's early space program, refers to the unique qualities of courage, skill, and determination possessed by test pilots and astronauts. It symbolizes the elite qualities needed to face high-risk challenges and push the boundaries of human exploration.

Occasionally, the pilots and astronauts in "TZ" lack these qualities. For every competent astronaut type seen, viewers meet nimrods like the crew of the first manned aircraft into space, Arrow One. The leader of these wrong-stuff astronauts concludes, "We have crash-landed on what appears to be an uncharted asteroid."

An asteroid with Earth's normal gravity, oxygen, and — one presumes — from which the sun appears the same size as from Earth. Any astronaut worth his spacesuit knows that Earth-like mass is required for such Earth-like conditions. Yet these yo-yos don't immediately conclude they're back on Earth. And that's exactly where they are. Just outside Reno, Nevada, in fact.

And speaking of asteroids...

9. A planet by any other name

The lack of fact-checking in science fiction TV series and movies often leads to the confusion of celestial terminology. Galaxies and solar systems get conflated, with any small celestial body labeled an asteroid. An asteroid is a rocky body lacking the gravity to form a spherical shape. As even some dwarf planets — like Makemake — have insufficient gravity to hold any sort of atmosphere, no proper asteroid will be Earth-like. Asteroids may be classified as "minor planets," aka "planetoids," and this seems to be what the "TZ" writers thought. (Heck, even the OG "Star Trek" ran afoul of this in "Metamorphosis," featuring a "planetoid" with Earth-like conditions.)

"TZ" featured two such Earth-like asteroids. The cemetery world in "Elegy" was one. The other so-called asteroid featured in "The Lonely" (Season 1, Episode 7). But that object is 6,000 miles north to south and 4,000 miles east to west. That gives it twice the volume of Mars! And Mars is over 22 times the volume of dwarf planet Pluto. That's no asteroid. It's a planet.

10. Mr. Microphone makes an appearance

Changes in TV technology aren't always kind to the programming of a previous era. Modern TVs feature tremendous increases in picture resolution, image clarity, and even how much of the recorded images we can see. This reveals not only extra detail but highlights defects that slipped past viewers in the past.

"On Thursday We Leave for Home" (Season 4, Episode 16) features an example of the latter. Buzz Kulik's on-screen credit precedes an extended shot of Captain Benteen (James Whitmore) and George Morris (Paul Langton). In it, a boom microphone pops into the bottom of the frame and moves back and forth and up and down throughout two cuts for nearly a minute of screen time. At one point, not only is the mic visible, but also the boom pole supporting it!

To be fair, this was probably not as apparent on a 1960s CRT TV as a modern flatscreen. The mic appears right at the bottom of the screen in what's known as the "invisible area," a portion of the TV signal outside the boundaries of a CRT TV's normal display area. In this instance, it still creeps into what's known as the "action-safe area" and would have been visible to some viewers even when it initially aired in 1963.

11. Revealing reflections

The series opener "Where Is Everybody?" (Season 1, Episode 1) hinges on the panic of Mike Ferris (Earl Holliman) when he stumbles into a town devoid of people, as if they all vanished an instant before he'd have seen them. This comes off very effectively, but if you pay attention when Ferris uses the payphone you'll see the head of a member of the film crew reflected in the phone booth glass, just below the name of the Cortez laundry. The man wears glasses and can be seen quickly moving back and forth.

Similarly, "And When the Sky Was Opened" (Season 1, Episode 11) features Air Force Colonel Clegg Forbes (Rod Taylor) freaking out when he casts no reflection in a mirror. His panic is undermined when you see his arm and hand visible at the left edge of the mirror.

It's unlikely either of these were visible on most TVs of the time, but they're plain as day on any modern TV.

12. Orbital eccentricities

"The Midnight Sun" (Season 3, Episode 10) marks another instance where the science portion of its science fiction premise trips over itself. The story posits that the Earth's orbit is perturbed, and thus slowly moving closer to the sun. Serling intones "The time is five minutes to twelve, midnight. There is no more darkness."

Of course, the Earth is a sphere that rotates on its axis as it moves along its orbit. Orbital distance does not determine day and night. For a perpetual day in New York, there must be an endless night elsewhere on the globe.

When the reveal arrives that the Earth drifting toward the sun situation is a dream, this illogical science becomes forgivable. Since when do dreams make sense? But that same illogical science returns with the episode's punchline. The Earth is actually drifting away from the sun into endless night. The rotational problem persists... unless you consider this episode's Earth to be flat.

13. Through a glass inconsistently

Continuity errors are common in TV series, including "TZ." Pitchers refill themselves, reflections appear where they shouldn't, and objects shift mysteriously. One such mistake occurs in the last episode of Season 3, "The Changing of the Guard" (Season 3, Episode 37). Professor Ellis Fowler (Donald Pleasence) speaks to Christmas carolers from his window, but his eyeglasses inconsistently appear and disappear.

This small mistake was nearly the final one the series ever aired, because — as reported in Marc Scott Zicree's book 1982 "The Twilight Zone Companion," — CBS dropped "The Twilight Zone" after three seasons, and Rod Serling left to teach at Antioch College. Ironically, "The Changing of the Guard" is a poignant story that explores themes of legacy, purpose, and the fear of becoming obsolete. In the episode, Professor Fowler faces retirement and questions the impact he's had on his students. It's a story about the value of one's life's work and the fear of being forgotten.

Serling's personal situation at that juncture shares some parallels with this theme. The temporary cancellation of "The Twilight Zone" marked a turning point in Serling's career. Like Professor Fowler, Serling grappled with questions about his legacy and whether he would continue to make a meaningful impact in the entertainment industry. Little did he know how relevant his show would be, even today.

Fortunately, "The Twilight Zone" would be revived as a mid-season pickup, and end after its 5th season.

And speaking of 5ths..

14. The sixth dimension... er, fifth

Our last error is one that itself has slipped into another dimension. The pilot episode "Where Is Everybody?" (Season 1, Episode 1) was submitted to CBS with a simpler title sequence, logo, and slightly different narration. Westbrook Van Voorhis served as narrator but was rejected for the series. When first choice Orson Welles proved to be too expensive, Serling stepped up to the plate as host — and the rest is history.

But that original title narration differed from what we know and love. In fact, it opened with an extra dimension. "There is a sixth dimension," Van Voorhis spoke sonorously. (It can be seen and heard here.)

CBS program executive William Edwin Self thought Serling made a mistake in that opening. According to "The Twilight Zone Companion," Self challenged Serling to explain what the fifth dimension was. Serling didn't have an answer. So the Zone moved one dimension closer to our own, but still impossibly out of reach... unless, of course, you moved into a land of both shadow and substance, of things and ideas.

Your next stop, the Twilight Zone!