How M*A*S*H's Alan Alda Pushed For The Series To Be More Than A Comedy

For one of television history's most beloved sitcoms, "M*A*S*H" was always walking a tight line. Premiering in 1972, it would go on for 11 years, depicting with raunchy humor and deep pathos the plights of a mobile surgical hospital on the frontlines of the Korean War. Early on, the show adopted the anarchic, bawdy comedic sensibility of the books by Richard Hooker (pseudonym for H. Richard Hornberger) and their 1970 Robert Altman film adaptation. But as with most long-running television shows, things change.

"M*A*S*H" was only nominally about the Korean War. It was hardly concerned with period-accurate detail (as plenty of the hairstyles demonstrate) and characters like series lead Hawkeye (Alan Alda) felt entirely out of time to begin with. Hawkeye's sense of humor was like the Marx Brothers, only translated to the then-current war in Vietnam. Korea existed in dialogue and major plotlines, but the feelings the show evoked were directly in conversation with contemporaneous issues.

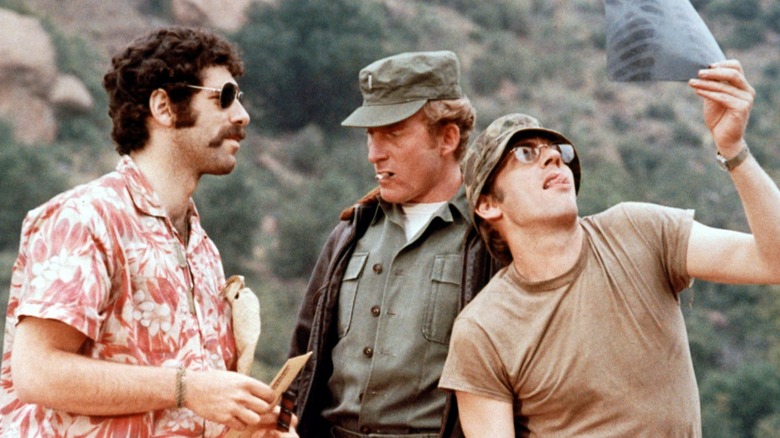

Part of the reason the show was as groundbreaking as it was was its pure willingness to face those issues head-on. Sexuality in the form of the many, many extramarital affairs characters got into on the front, or even queer issues, could be discussed. And the ever-lingering threat of the war hung just alongside the shenanigans of Hawkeye and Trapper (Wayne Rogers), Radar (Gary Burghoff), or B.J. (Mike Farrell).

Alan Alda was actually one reason the show resisted the easy comedy of life during wartime. In many ways, he became the face of the show at its "most preachy," as some critics claimed of the show's later years. But his influence gave the series some of its unforgettable dramatic moments.

Previous takes on M*A*S*H

As devised by Gene Reynolds and Larry Gelbart, who adapted the show from the movie and books and would serve as executive producers for the first half of the show's run, "M*A*S*H" was going to be different. It would distinguish itself from sitcoms of the day with its single-camera, cinematic style, and a more subdued laugh track that would disappear for long stretches of time. Even getting the laugh track out of the operating room meant the show would be unique from its peers.

Whether it was the movie or the book, "M*A*S*H" was a hard sell. Both takes on the Korean War were grimly cynical, with none of the charm the television show ultimately extracted from the setting. The book largely used the wartime setting as a jumping-off point for boozy antics, and the movie took that nihilism a step further, fusing the wild behavior of the "meatball surgeons" with the carnage to brutal effect. Robert Altman, director of the 1970 film, was famed over the course of his career for crafting chaotic environments with overlapping dialogue and his penchant for the cacophonous and sprawling. While the movie spoke to anxieties around Vietnam, it did so in an angry, oblique way.

The show would need to take a different approach. Early on in the show's run, it looked quite a bit like a watered-down take on both previous sides of the franchise. The fun was a bit more family-friendly to hit as many viewers as possible, and the "War is Hell" moralizing had to be relegated to euphemistic dialogue, no room for any of the bloody corpses depicted by Altman. But that tension in the show is what gave it its lasting power – its battle for the soul of America.

More than a comedy

Alan Alda was a big part of that battle. For most of his career as a known actor, he's used his platform to vouch for feminism, according to Vanity Fair. In fact, his reputation as a liberal and progressive voice could probably be said to overshadow his already prodigious, eclectic career as an actor, writer, and director. Without his being on one of the biggest shows on television, who could say if that would have happened?

Early in the development phase of "M*A*S*H," when he first met with showrunners Larry Gelbart and Gene Reynolds, Alda found kindred spirits. As he told the New York Times in 2022, Alda felt the show's pilot had "a terrific script," but he had to reassure himself that the writers understood some of his reservations. The night before the first rehearsal, he met with Gelbart and Reynolds in Los Angeles to ask them some questions.

What he wanted to avoid was what the book (and the movie in some ways) embraced: the wild hijinx of the front, the dark comedy of the meatball surgery, the misogyny. As he recalled, he needed the writers to agree "that it would take seriously what these people were going through. The wounded, the dead. You can't just say it's all a party."

Alda's commitment to portraying the reality of war was necessary at a time like the early '70s, still some years before the Vietnam War would end. If "M*A*S*H" would be sharing television airwaves with the "first televised war," it would do well to limit the goofy antics, even if just a bit. Executives might have bristled at the series' bolder episodes, but that was "M*A*S*H."

Real stories

Alan Alda was just one reason that "M*A*S*H" told all the sides of its characters' wartime experiences. Speaking with the New York Times, Alda referenced the groundbreaking work of legendary sitcom producer Norman Lear, particularly "All in the Family," which premiered the season before "M*A*S*H." That show demonstrated that audiences would be willing to follow shows that discussed difficult and timely topics.

Such freedom let "M*A*S*H" approach stories with frankness and its own comedic sensibilities, like the groundbreaking season 2 episode "George," which dealt with a soldier's homosexuality. Other episodes, like season 1's heart-wrenching "Sometimes You Hear The Bullet" sparked network executive rage for its near-total lack of laughs. As Alda recalled to the New York Times, "Some guy in charge of programming said, 'What is this, a situation tragedy?'" The balance eventually shifted more in that direction, with the womanizing and practical jokes of the show's early years (borrowed directly from the previous iterations of the franchise) slowly disappearing in favor of pathos.

When asked about why the show has had such a significant legacy, Alda replied that what "sinks in with an audience is ... an awareness that real people lived through these experiences." To watch the show now, it's easy to see the melancholy emerge from its depiction of the Sisyphean task of simply keeping men alive during war. The show's 11-year run nearly quadrupled the actual duration of the Korean War, which gave it a purgatorial feeling that might have been more true to how war is experienced than anything else.