Tommy Lee Jones Is The Best Actor Ever

If you ever happen across Tommy Lee Jones in a public setting, should you find yourself sharing an elevator with him or spot him across the room in a restaurant, do yourself a favor and leave him be. If you're at all adept at reading body language, you should realize fairly quickly that the man is a walking "do not disturb" sign. Should you try to engage, know that he will swiftly and bluntly shut you down. Whatever bond you feel you've formed with Jones, it doesn't extend beyond the movie theater or your television screen. Not for him.

If you ever get the opportunity to interview Tommy Lee Jones, prepare. Do your research, write your very specific questions down well in advance and do not deviate. If you ask good, thoughtful questions, you'll get a good interview. Do not try to have a conversation. If your inquiries ramble or, god forbid, you get personal, best-case scenario is he'll walk out of the room. Worst-case, he'll humiliate you like he did former New York Times film reporter Bernard Weinraub.

Is this misanthropy? Not in actor Richard Jones' eyes. As the longtime friend of Jones told Texas Monthly, "You just need to remember that Tommy's got a lot of cowboy in him. He's got a cowboy's skepticism about people he doesn't know. He doesn't feel any need to open up to them just because they are asking him questions."

Jones comes by this skepticism naturally. He was raised in Midland, Texas by a cowboy-turned-roughneck before riding off to the Ivy confines of Harvard in the 1960s. He roomed with Al Gore, and undoubtedly encountered young men of East Coast privilege who lacked his ruggedness and keenness of mind. Somewhere along the line, he developed a low tolerance for inauthenticity and walled himself off from people he deemed unserious. He's channeled this surliness into many of his characters – most famously U.S. Deputy Marshal Samuel Gerard in "The Fugitive," who seems to only trust/respect the handful of officers under his command. They're his people. But there's a flicker of warmth lurking within Gerard, which makes these characters desperate for his approval.

This is why so many people who know better try to ingratiate themselves with Jones in real life. They, too, want to feel worthy of this no-nonsense Texan. He is a powerfully magnetic movie star in this sense, but it took some time to hone that agreeably gruff on-screen persona.

The breakout

Jones graduated from Harvard in 1969 with a BA in English, but he'd been bitten by the acting bug. He moved to New York City, and booked a few Broadway gigs while working steadily on the ABC soap opera "One Life to Live." After impressing as a disillusioned escaped convict in the above-average Roger Corman-produced prison exploitation flick "Jackson County Jail," Jones landed the role of Vietnam vet Johnny Vohden in John Flynn's cult actioner "Rolling Thunder."

Jones' Johnny registers strongly as a former POW who's failed to adjust to a post-Vietnam United States. Like many war veterans, he keeps his despair and fury to himself. He's racked with shame and devoid of purpose. So when his friend and fellow former internee Major Charles Rane (William Devane) asks his help in taking revenge on the border-town thugs who killed Rane's wife and child, Johnny doesn't hesitate to pitch in. "Let's go clean 'em up."

Screenwriter Paul Schrader's dialogue for Johnny is terse. Most actors would've taken this as an invitation to portray Johnny as a deranged, dead-eyed warrior with a death wish. Jones, however, uses his chiseled features and sunken eyes to convey a deep sadness and, most acutely, a sense of shame. When Johnny tells a sex worker he's "gonna kill a bunch of people" prior to the climactic shootout in a Juarez whorehouse, his robotic delivery is kind of depressing because, prior to this, Jones has imbued this killer with a soul. He's gotten us to mourn for this spiritually adrift working-class Texan who was betrayed by his country. In some ways, we ache more for Johnny than Rane (who's close to a full-blown psychopath by this point).

As he would do many times throughout his career, Jones finds the tender areas lurking within a hard man, a man we'd like to understand and, perhaps, have a beer with. Johnny may not be the quintessential Jones character, but he was the entry point to a career that would quickly, if briefly, blossom.

The career

After dazzling as Doo Lynn, wild-card husband to Sissy Spacek's Lorretta Lynn in Michael Apted's "Coal Miner's Daughter," Jones knocked about Hollywood trying to build up his leading-man credentials. He set off sparks with Sally Field as a rowdy ex-boxer in Martin Ritt's disappointingly formulaic rom-com "Back Roads," and doubled down on his roguish persona as a thrill-seeking pirate in the underrated 1983 pirate romp "Nate and Hayes." Alas, these films were not hits, which killed the momentum Jones had built up coming out of the '70s. He was fine as an ex-con father opposite Martha Plimpton in 1984's "The River Rat," and in his tough-guy element as a hard-driving thief in the ludicrously entertaining "Black Moon Rising," but he was soon relegated to supporting roles in films that would've been skippable without his presence (two exceptions: Mike Figgis' nifty neo-noir "Stormy Monday" and Andrew Davis' sturdy Cold War thriller "The Package").

Jones' career reignited in 1991 with his deliciously sinister turn as New Orleans businessman Clay Shaw in Oliver Stone's "JFK." He received his first Oscar nomination for this very un-Jones-like performance, which he followed up with a wild plunge into action-movie villainy as unhinged ex-CIA operative Billy Strannix in Davis' "Under Siege." Greenlit as the first A-level, mainstream star vehicle for Steven Seagal, Davis, who'd played an integral role in giving the pony-tailed martial arts master a career via "Above the Law," cannily curtailed Seagal's screen time and let Jones commit cinematic grand larceny. While "Under Siege" was easily the best-reviewed Seagal film to date, it was arguably more important to Jones' career in that it showed he could dominate a movie from a supporting position. People went to see Seagal, but they came out raving about Jones.

Davis clocked this, and gave him the role that made him one of Hollywood's most in-demand badasses.

A deputy in search of a doctor in search of a one-armed man

Stealing a movie from Steven Seagal was one (exceptionally easy) thing. Yoinking one away from Harrison Ford was quite another. But "The Fugitive" was a unique project that, as detailed in the engrossing Rolling Stone oral history of its production, deprived its star of one of his greatest strengths: Being a relentlessly paced chase thriller about a man frantically trying to prove he didn't kill his wife, it was logistically and emotionally implausible to give Ford a love interest or let him quip his way into our hearts. The fun of this film had to come from somewhere else.

Enter Jones and his merry band of U.S. Marshals.

Gerard is a wheelhouse character for Jones. He's a no-nonsense lawman who's smarter than everyone in the room, knows this, and treats it as a curse. He's perpetually annoyed, even when dealing with his own people (especially when they're using words around him that have no meaning). But he will not be deterred. Gerard will get his man. And he does. And watching Jones suffer nary a fool while playing this cat-and-mouse game is a joy.

Again, this is the Jones we want to not just know, but impress, to show him we're on the same intellectual level. That's a strange attribute for an actor, but Jones invites it. It's an immensely satisfying act that earned him the 1993 Best Supporting Actor Oscar, and, at long last, placed him on the industry's A list.

The '90s and beyond

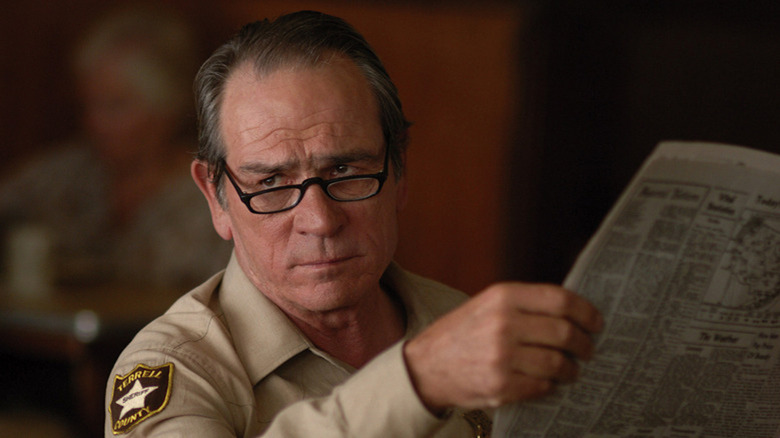

Jones was in danger of being typecast, but, 30 years after that triumph, he's maintained a deft balance between Tommy parts and more demanding feats of immersion. Sometimes it's hard to tell the difference because he makes it look so damn easy. That capacity for tenderness is brilliantly utilized opposite a tantrum-throwing Jessica Lange in "Blue Sky," and his deadpanning as Agent K in "Men in Black" is unbeatable. He's a beaten-down Gerard in the Coens' "No Country for Old Men," and stirring as anti-slavery crusader Thaddeus Stevens in Steven Spielberg's "Lincoln." And he directed himself to one of his finest performances in the underseen "The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada."

There were missteps. Though the film was a smash, Jones's Harvey Dent in "Batman Forever" is a shouty, snarling bore. Jones was generally pleased with the process, but he did get snappish with co-star Jim Carrey. When the comedy superstar tried to make idle conversation with Jones (whom Carrey admired), the newly minted Oscar winner told him, "I cannot sanction your buffoonery." There was also "Blown Away," a limp mad-bomber action-thriller for which Jones ill-advisedly adopted an Irish accent. It's undoubtedly the worst performance of his career.

But these slip-ups are rare. Jones typically plays to his hard-nosed strengths and delivers with a minimum of actorly fuss. He's renowned for showing up to set with an expectation of moving through the day swiftly. He's efficient. You've hired him to do a specific job, and he's going to give you everything you need in a take or two – and if you're not getting what you need, that's a you problem. But there's one film in his oeuvre where I wonder if he needed a bit more time to work up into the necessary lather. Because it's unlike anything else he's ever done, and, to my mind, it's as horrifying a portrait of American greatness as any actor or filmmaker has ever dared to capture.

The defining performance

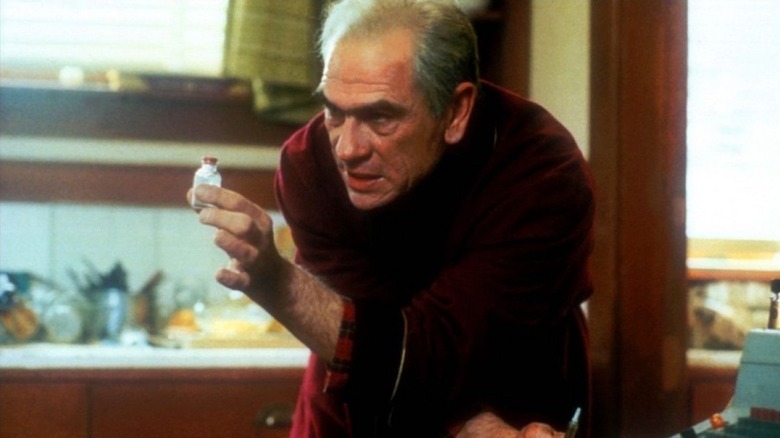

Ron Shelton's "Cobb" is baseball's "Raging Bull." It's a harrowing biopic about arguably the best baseball player of all time and, not so arguably, an absolute monster. When Ty Cobb retired from Major League Baseball in 1926, he was the game's all-time hit leader (his record stood until Pete Rose surpassed it in 1985), but the stories of his violence, racism, and all-around misanthropy were legion. He was lauded as an athlete, but feared as a human being, and Jones holds nothing back in exploring the depths of the legend's malignant psyche.

Shelton's film is based on Al Stump's "Cobb: The Life and Times of the Meanest Man in Baseball," which was the author's corrective to his ghostwritten, Cobb-approved autobiography "My Life in Baseball: A True Story." According to Stump, his time spent with a dying Cobb was a booze-and-drug-fueled nightmare; he dodged bullets, absorbed punches, and listened to the great man spew off bigoted invective with impunity. He also claims Cobb confirmed that his mother murdered his father, and suggested that he himself murdered a man before a Tigers game in 1912.

Many of Stump's accounts have been challenged, but Shelton's film is not about setting the record absolutely straight. It's about reckoning with the fact that the greatest practitioner of America's pastime was the unrepentant embodiment of everything that is awful about America; aside from his on-field transgressions, he spitefully hoarded his wealth and shut out his family because all he knew how to do was hate. And only Tommy Lee Jones could, through his devilish guile and keenly projected intellect, draw us close to a creature as hideous as Tyrus Raymond Cobb.

The Georgia Peach in all his virulent glory

Robert Wuhl is perfect casting as Stump. He's alternately starstruck and appalled — eager to maintain his journalistic integrity, but seduced by the darkness of baseball's first celebrity. He's us. Jones' Cobb, on the other hand, is Satan in stirrup socks. He is, to quote the great Charlie Murphy, a habitual line-stepper, although his idea of grinding his boots on your couch is whizzing a couple of bullets over your head for s**ts and grins. He's a bucking bronco, but when the diabetes and complications from cancer kick in, he's given to pathetic bleats of honesty. Somewhere in these moments, as he tears ass towards the abyss, is a man who knows he's an irredeemable bastard.

We want to hear his confession, and Jones, no matter how abusive Cobb gets, keeps us believing that expiation is possible. But Cobb, even after he coughs a pint of blood into a hotel sink and squeals for an ambulance like a scared child, always reclaims the upper hand. He's aware Stump has the goods on him, but he will die knowing that, contractually, Stump must tell his version of the truth. And he knows that no matter how many curveballs history throws, his numbers are his numbers. They're on his plaque in Cooperstown, and they're not going anywhere.

Jones leaves us aghast at the terrible tenacity of Cobb — relieved that he is gone, but in awe of the toxic forces that created him. Like "Raging Bull," you often want to look away. But there's something about this wretched man that keeps us riveted to the screen. That's the brilliance of Tommy Lee Jones, tempting us to get to know a man who demands to be known only on his own terms.