Robert De Niro Is The Best Actor Ever

When Robert De Niro came out swinging, rhetorically, at Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump in 2016, it was the most stirring and surprising performance he'd given in years. "He's so blatantly stupid," he said in a campaign ad. "He's a punk. He's a dog. He's a pig. A con. A bulls**t artist. A mutt who doesn't know what he's talking about." Then he lowered the boom: "I'd like to punch him in the face."

Though the actor had long been on the record as a Democrat, he'd never been this emphatic about a political position in his public life (there was his unfortunate dalliance with quackish anti-vaxxer theories, but he took a non-committal position on the actual science). In fact, he'd never been emphatic about much of anything. Anyone who'd watched the actor squirm his way through an interview knew full well that the man wasn't much of a talker. When he did speak, he tended to be soft-spoken. He seemed almost embarrassed to be holding forth on any subject, even acting. He did not come off as a man who believed in himself.

De Niro's discomfort in a press setting gave us permission to not dig too deeply into his private life, and I happily kept my distance. De Niro is a method-acting burrower. Watching him alter his appearance, physical bearing, and speech from film to film is a magic act. I didn't want to know how he did it, I just wanted to see him do it. So while I certainly agreed with him about Trump, I was also strangely disappointed that his carefully maintained facade had fully crumbled. It felt like one of filmdom's most intriguing enigmas had been solved.

The breakout

In 1963, Sarah Lawrence theater professor Wilford Leach set out to make a film with two of his students, Cynthia Monroe and Brian De Palma. Many of the actors cast in the movie traveled in the same creative circles as the directors, which allowed a young De Niro to stand out. "Nobody knew him," said De Palma. According to Glenn Kenny's "Anatomy of an Actor: Robert De Niro," the actor auditioned with an improvisation for Clifford Odets' "Waiting for Lefty." "He went out and then came back in like a powerhouse," said DePalma. "He came on like Broderick Crawford — reading a speech to the cabbies in the union hall. He was simply great — that I remember."

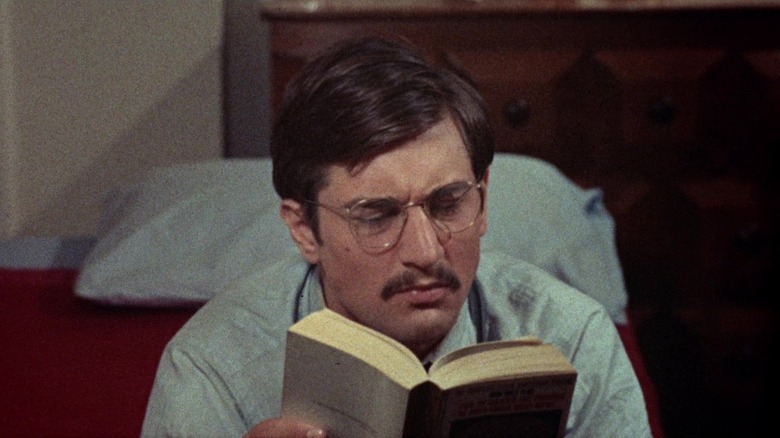

De Niro landed the role of Cecil in what would become the French New Wave-influenced comedy "The Wedding Party," which, while shot in '63, wouldn't receive a theatrical release until 1969. That it was released at all was due to the cult success of De Palma's second feature-length film, "Greetings." This sporadically hilarious counterculture satire stars De Niro, Gerritt Graham, and Jonathan Warden as a trio of Greenwich Village eccentrics desperate to devise ways to avoid getting sent to Vietnam, and it benefitted commercially from the anti-war protests and the furor surrounding the 1968 presidential election. But it's not an angry film. De Palma pokes fun at everything from the conspiracy theories provoked by the Warren Commission's findings to the advent of computer dating.

De Niro's character is something of a funhouse mirror surrogate for the director. He's an aspiring filmmaker whose voyeuristic tendencies cross the line into straight-up peeping Tom territory. De Palma's self-critical examination of voyeurism would become a career-long fascination, but De Niro's blank-slate nature imbues his character with quiet menace. He's not idealistic like Keith Gordon's resourceful teenage hero in "Dressed to Kill," nor is he amusingly pathetic like Craig Wasson's struggling actor in "Body Double." He's distressingly comfortable with his transgressive kink.

De Niro eschews the stage

There was no avalanche of plaudits for De Niro's work in "Greetings," nor for his equally unnerving turn in De Palma's jolting follow-up, "Hi, Mom!," but the actor's unnerving gift for shunting us onto the malfunctioning wavelength of damaged, dangerous misfits was darkly blossoming in these movies. The times were changing and so were the movies, and there wasn't an actor more attuned to the country's haywire frequency than De Niro.

Unlike many of his celebrated peers, De Niro does not have a New York City theater origin story. He studied at Lee Strasberg's Actors Studio and the Stella Adler Conservatory, and received high marks from both. But he went straight into movies, and, to date, has only one prominent Broadway credit (via 1986's production of Reinaldo Povado's "Cuba and His Teddy Bear"). When American theater legend Elia Kazan directed him in 1976's "The Last Tycoon," he praised De Niro's uncommon commitment to rehearsal. So why has De Niro sedulously avoided the stage? Perhaps because he was too busy redefining film acting, and he knew it.

De Niro hits his prime

After earning praise for his portrayal of doomed, dim-witted pro baseball catcher Bruce Pearson in "Bang the Drum Slowly," De Niro hooked up with Little Italy-born auteur Martin Scorsese for "Mean Streets." As Johnny Boy, the reckless albatross of a best friend to the conflicted Charlie Cappa (Harvey Keitel), De Niro threw a vicious charge into every scene. Francis Ford Coppola, who'd tried to cast him in "The Godfather" (De Niro took a part in "The Gang That Couldn't Shoot Straight" instead), landed him as the young Don Vito Corleone in "The Godfather Part II." De Niro earned his first Academy Award nomination for his portrayal and won.

He reunited with Scorsese in 1976 for "Taxi Driver," which cemented his status as his generation's Marlon Brando. But there was nothing dangerously sexy about De Niro's Travis Bickle — or any of his 1970s characters, really. His affinity for emotionally stunted antiheroes was threatening to edge into self-parody during the 1980s until he committed to Martin Brest's buddy comedy "Midnight Run." This was the departure that saved his career. His comedic timing is spot-on, and his chemistry with Charles Grodin's mob embezzler is lightning-in-a-bottle perfection.

This cracked everything open for De Niro. Maybe too open. He worked more readily, but also leaned into unearned histrionics. There was a slump on the horizon.

The slump and the slumpbuster

De Niro took a lot of critical grief for his early 1990s choices, but he was being judged against his own brilliance. He was way too much actor for some of these parts (e.g. as the arson investigator in "Backdraft" and the conscience-stricken priest in "Sleepers"), but he's sensational in "Cape Fear," "Mad Dog and Glory," and "Heat." His portrayal of stoner criminal Louis Gara in "Jackie Brown" is, low-key, one of his finest performances. Here he works a variation on the introverted, shy guy De Niro we see in interviews — that is, until the angle he's working with Bridget Fonda's Melanie goes sideways. Louis abruptly hitting his breaking point in the shopping mall parking lot is a darkly ecstatic fit of violence that sends us into hysterics because we keep waiting for the De Niro to come out in this schlub.

The 2000s were a period of great prosperity for De Niro, in that he cashed hefty paychecks by turning up in garbage like "Showtime," "Meet the Fockers," and "Righteous Kill" (where he plays a game of phone-it-in chicken with Al Pacino). He recovered with a fully-engaged performance in John Curran's "Stone," and brought his A-game to "Silver Linings Playbook," "The Intern," and "The Irishman." It's frustrating that many critics harp on De Niro's physically labored beatdown of the store owner in the early going of Scorsese's film because the actor is heartbreakingly frail in the final act. Watching him lose his vitality and pick his coffin (because he has no family who cares to bury him) is a depressing compliment to the performance De Niro could never top because you can't top arguably the greatest film performance of all time.

The defining performance

Jake LaMotta was a wreck of a human being. He was a great fighter who held the world middleweight title from 1949 to 1951. He was born to fight, to hurt people, and he did so relentlessly in and out of the ring. He did his damage in tight quarters and endured some of the most hellacious beatings in boxing history. Sportswriters who watched him in his prime say he had an iron chin. You could pulverize his face into hamburger, but if you wanted to put his lights out you better pack a lunch because it was going to take all goddamn day.

De Niro didn't just study LaMotta for "Raging Bull," he became him. His real-life subject participated in the actor's rigorous training and said he could've been one of the 20 best middleweight pugilists of all time. Then Scorsese paused the production for several months so De Niro could pack on 70 pounds to become the slovenly, showbiz aspirant version of the hateful palooka.

There isn't anything shy about LaMotta. He is loudly, disgustingly violent. He is all appetite, and he is nothing like Johnny Boy, Travis Bickle, or Rupert Pupkin. He can function within society, and did so for 95 years, even though he absorbed thousands of punches from men whose fists are essentially lethal weapons. He was a survivor who subsisted on hate. I don't think LaMotta was quintessentially American, or quintessentially anything. He was a ball of self-loathing who paid his penance in the ring but never went down. His very existence was an act of resentfulness.

Scorsese's film wears you out. It opens with De Niro bouncing out a beautiful, bulb-flash-lit solo dance to the Intermezzo from Mascagni's "Cavalleria rusticana," then backs you into the corner and busts you up until the closing credits. And you accept the punishment because De Niro, the shy kid raised by sensitive artists, is dishing it out. Where does this savagery come from? It's in all of us. Going there would destroy most of us. Maybe touching those cruel depths and pulling back provoked De Niro's disdain of Trump. And maybe he's just the man to make him kiss the canvas.