11 Major Influences On Martin Scorsese

If you ask Martin Scorsese about his movies, he will likely talk at length about the work of other filmmakers. This was especially true of an interview he gave to BBC Culture, in which he summarized his love of — and debt to — the past, saying, "I look at the filmmakers of the past and many filmmakers of the present and I have really nothing but admiration ... more than admiration, I survive from them, I live off that, I live off the inspiration I get from them ... Artists need to know the past and know what's been done."

Years prior, in a discussion with British journalist and presenter Barry Norman, Scorsese named five influential films that he sought to collect when he had the means to do so. They were John Ford's "The Searchers," Powell and Pressburger's "The Red Shoes," Federico Fellini's "8 ½," Orson Welles's "Citizen Kane," and Luchino Visconti's "The Leopard."

The influence of these filmmakers and others vary in their effect on Scorsese. Welles and Ingmar Bergman opened Scorsese's eyes by transgressing conventions and exploring the medium's many possibilities. Their films were foundational experiences for the young filmmaker but did not influence his work with the direct detail of Francois Truffaut, Kenneth Anger, and Satyajit Ray, whose respective approaches to editing, soundtrack, and social milieu are clearly seen throughout Scorsese's features.

Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger

The films of Powell and Pressburger significantly influenced a young Scorsese, especially the 1948 ballet drama "The Red Shoes." "It's a film that had a very strong impact on me," Scorsese told the Guardian, "the nature of the storytelling, the images, the editing, the camera movements, the use of music, the faces ... it was a very dark story."

Another favorite was "The Tales of Hoffmann," Powell and Pressburger's Technicolor opera from 1951. "I became kinda obsessed and entranced by the picture," Scorsese explained to Studiocanal, "the music and the choreography of both the dancers and the camera told the story ... and this is something that stayed with me in my own work over the years." Scorsese's famous use of music and image can be traced, at least in part, to this British opera film.

Scorsese was not the only boy in the neighborhood to enjoy "The Tales of Hoffmann." Before he started renting the 16mm print on a regular, almost religious basis, another up-and-coming filmmaker often signed out the film. "In those days you had to go and rent a projector and a 16mm print ... It was always available, nobody else ever took it out," George A. Romero told a KVIFF audience. " ... Then all of a sudden somebody else started to book it. It turned out to be [Martin] Scorsese. We were the same age. He lived in Brooklyn and I lived in the Bronx and we were the only two guys that were taking out this movie."

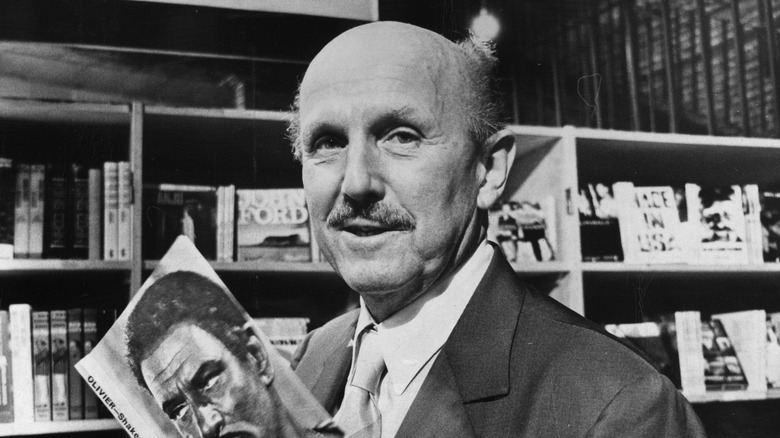

Roger Corman

Legendary B-movie filmmaker Roger Corman ranks among the most influential people in Hollywood history. Francis Ford Coppola, Jonathan Demme, Ron Howard, and James Cameron all got early breaks under the producer's tutelage, and so did Martin Scorsese. In 1972, Corman hired Scorsese to direct "Boxcar Bertha," a depression-era gangster film in the violent mold of "Bloody Mama," which Corman directed two years prior.

In an interview for Tharunka magazine, lead actress Barbara Hershey argued that Corman's emphasis on seediness and violence "crippled" the film, but Scorsese described him as "a great professor," adding that Corman taught him about the "realities of the marketplace ... There had to be a chase scene here ... a touch of nudity there ... He didn't apologize for that ... I didn't mind embracing the Corman formula" (via Time). Corman's most enduring lesson? The importance of logistics. "The one thing I learned from Roger was total preparation," Scorsese said during an interview for the "Corman's World" documentary. "I've never seen somebody be so extraordinary in terms of pacing of a picture [and] knowing the audience that it's for."

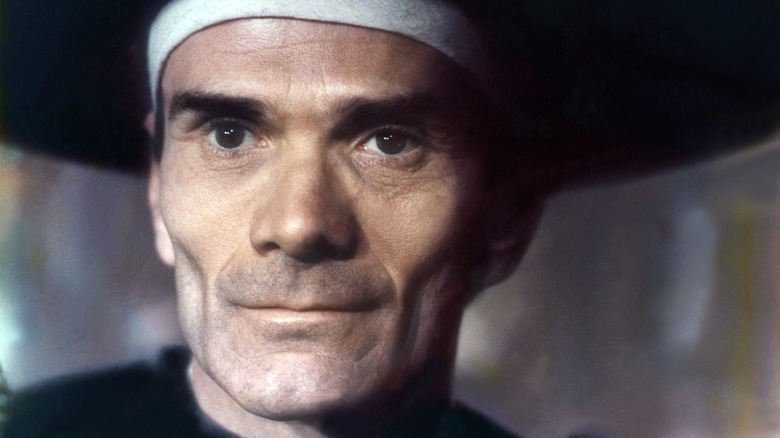

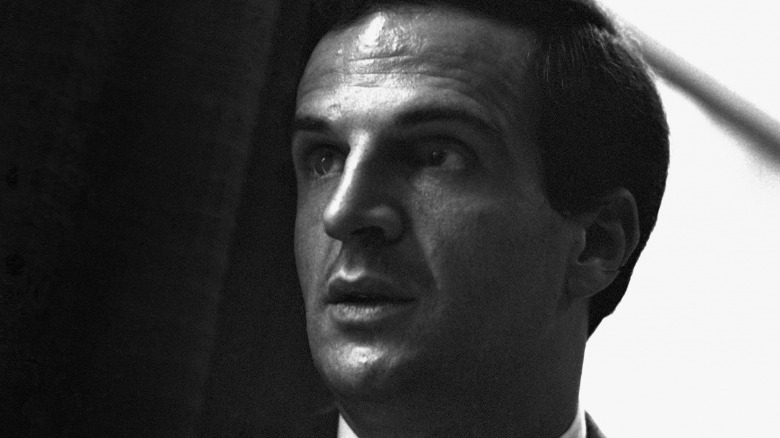

Kenneth Anger

Kenneth Anger was an experimental filmmaker known for "Fireworks," "Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome," and especially "Scorpio Rising," which Scorsese saw at a private screening in the mid-1960s. Peter Docherney's book "Hollywood's Copyright Laws" recounts how Anger's use of imagery and music — namely Elvis Presley, Ricky Nelson, and other rock & roll acts — encouraged Scorsese to make bold musical choices in his own short films, such as the 1967 allegory "The Big Shave," which pairs a strange bathroom scene with the beat of Bunny Berigan's "I Can't Get Started."

Scorsese developed his synchronous style through to "Mean Streets" in 1973, which opens with a montage of New York life tailored to the structure of "Be My Baby" by The Ronettes. Such moments have been a fixture of Scorsese's aesthetic ever since, with the manic helicopter sequence of "Goodfellas" serving as perhaps the very best example. "Martin Scorsese learned about soundtracks from me," said Kenneth Anger, who died on May 11, 2023 (via Guardian).

Pier Paolo Pasolini

In a DGA conversation with Quentin Tarantino, Scorsese cited Pier Paolo Pasolini's "Accattone" as a key influence of his youth. Scorsese caught the film around the same time as John Cassavetes' "Shadows," and the two movies became a double bill of influence. Whereas "Shadows" taught him about improvisation (more on that later), "Accattone" presented a bleak vision of urban Rome with its gallery of pimps and pushers set against the city's Catholic culture and iconography. It was another realist film of "world cinema" that drew parallels with Scorsese's environment and inspired him to create his own account of it, which he did just over a decade later with "Mean Streets."

Pasolini stirred Scorsese's Catholicism further with "The Gospel According to St Matthew," a neorealist interpretation of the New Testament with an aesthetic so true-to-life that when Scorsese considered doing a Gospel documentary, he scrapped the idea because, per Film Comment, "Pasolini did that." Eventually, Scorsese found his own vision with "The Last Temptation of Christ."

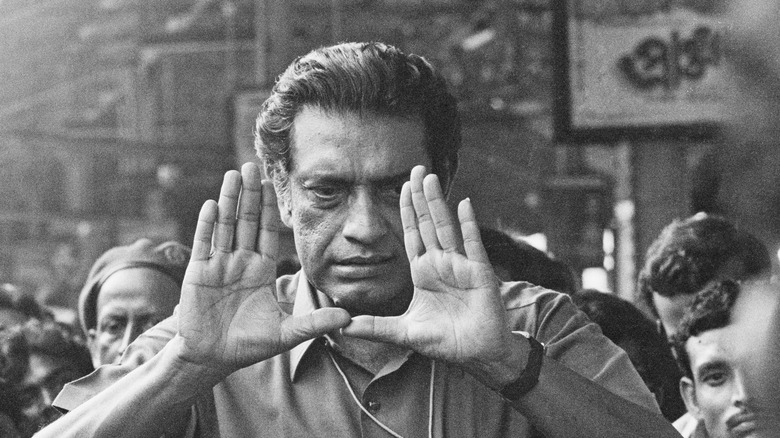

Satyajit Ray

Scorsese has praised Indian director Satyajit Ray on numerous occasions. In 2009, the director told a Smithsonian audience, "His films opened my mind and inspired me ... his influence was incalculable." Television introduced Scorsese to Ray's Apu Trilogy in his formative years and the impression was profound despite the commercials and the English dubbing.

Ray's depiction of Indian village life inspired Scorsese to consider his own surroundings; the Lower East Side may have been very different to the Bengali village of "Pather Panchali," but the humanity of Ray's filmmaking drew a strong parallel for the young, would-be filmmaker. "I'm a Sicilian American and we have our own little village ... you can't imagine anything more different, and yet we identified immediately as human beings, as people, as family."

Some 20 years later, Scorsese channeled this realist, "filmmaking from below" aesthetic into "Mean Streets," which the director described in a feature-length commentary as not so much a movie but a "statement of who I am and how I was living."

Orson Welles

Orson Welles's influence is felt throughout 20th and 21st-century cinema. "Welles inspired more would-be directors than any other filmmaker since D. W. Griffith," Scorsese stated "A Personal Journey with Martin Scorsese Through American Movies," and the most consequential film he ever made was, of course, "Citizen Kane."

In an AFI interview, Scorsese discussed how "Citizen Kane" transgressed the "hidden camera" aesthetic of classical Hollywood cinema with a medley of self-referentialism and wide-angle lenses that, upon his first viewing on the family's boxy, black-and-white television, taught the young cinephile about editing and camera positions. "Welles was the one to open up the Pandora's box of cameras flying up in the air," he added.

Another important film is "The Trial," the 1962 psychological drama adapted from Franz Kafka's novel. As writer, director, and supporting actor, Welles presents Kafka's paranoid nightmare with stark camera angles and brutalist locales graded with a shadowy, monochrome palette. Scorsese screened "The Trial" to the crew of "Shutter Island," which packages a similar sense of delusion into its strong, pulpy genre trappings.

Alfred Hitchcock

Alfred Hitchcock made a large impression on Scorsese at an early age. He told the Oscars about how he enjoyed "Dial M For Murder" on its release in 1954, despite it being a 2D showing (it was shot in 3D during the 3D craze of 1953). Years later, in 1980, Scorsese finally saw the film in its original three-dimensional form and it was a "revelation ... Hitchcock used the 3D very expressively and somehow deepened the emotions ... It brings the inner worlds of the characters very close to the audience." "Dial M For Murder" was required viewing for Scorsese's crew during the production of "Hugo," which creates arresting scenes of 1930s Paris with the modish 3D technology of the late 2000s and early 2010s.

If "Dial M For Murder" was a technical lesson, then "Rear Window" — Hitchcock's second film of 1954 — was a thematic one that developed Scorsese's interest in morally dubious protagonists. "Should he be doing what he's doing?" Scorsese asked the AFI, referring to James Stewart's voyeuristic lead character, "What kind of a guy is this? He's our hero!" Similar questions could be asked of Travis Bickle, Jake LaMotta, and Henry Hill.

Further influence comes from the shower scene in "Psycho," which shaped a fight scene in "Raging Bull;" and from Hitchcock's much-celebrated "Vertigo," the film that entered Scorsese's "DNA" and "consciousness" (via BBC Culture). Then there's "The Key to Reserva," a 10-minute sparkling wine commercial and faux documentary in which Scorsese presents a skillful imitation of Hitchcockian visual grammar replete with a Saul Bass-style credit sequence and elements of Bernard Hermann's score from "Vertigo."

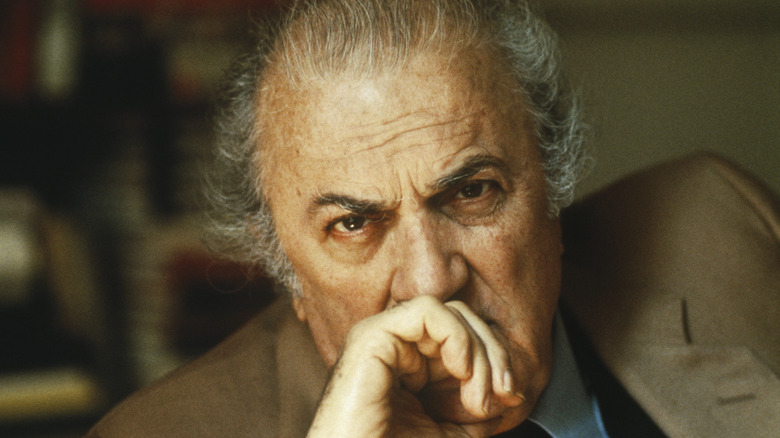

Federico Fellini

In the documentary "My Voyage to Italy," Scorsese explained that Italian cinema left an "indelible mark" on him in his childhood. Neo-realist figures such as Roberto Rossellini and Vittorio De Sica shook him with their harsh depictions of war-torn Italy, especially Rossellini's "Rome, Open City," which moved his grandparents to tears and reminded the young Scorsese of where he came from and what his family had left behind.

Other highlights include De Sica's "Umberto D." — "the pinnacle of neorealism, Scorsese told the Hollywood Reporter — and Ermanno Olmi's dissolve transitions in "Il Posto," which Scorsese replicated in "Raging Bull." However, as impactful as neorealism undoubtedly was, the most influential Italian filmmaker in Scorsese's life is most likely Federico Fellini, whom he called "cinema's virtuoso."

Fellini's influence on Scorsese is manifold. For example, "I Vitelloni's" humorous depiction of idle young men helped stoke ideas for "Mean Streets." "If he could do it about Rimini (the director's town of birth)," Scorsese recalled to Charlie Rose, "then I could do it about Elizabeth Street."

"I Vitelloni" was undoubtedly important, but it wasn't until 1963, some 10 years later, that Fellini made "8½" and reached what Scorsese considers to be his "absolute mastery" of the medium. "'8½' redefined my idea of what cinema was — what it could do and where it could take you," Scorsese wrote in Harper's Magazine.

Francois Truffaut

Francois Truffaut was a leading figure of the French New Wave and a marked influence on Scorsese, who referred to the Frenchman when challenging Haig Manoogian, his much-loved film professor. "Truffaut said when he's cutting a film going one way, he recuts it to go another way," Scorsese said. "That's nonsense," Manoogian replied, "[Truffaut] wouldn't do that" (via DGA).

It's unclear if Scorsese's anecdote was "nonsense" or not, but the young filmmaker maintained his deference to Truffaut through college and into his career, mirroring the director's use of energetic montages and potent voiceover narration in films such as "Goodfellas," "Casino," and "The Wolf of Wall Street." Scorsese derived the bulk of this style from "Jules and Jim," Truffaut's 1962 romantic drama that impressed a resounding energy on Scorsese and shaped the punchy, vibrant edge of his aesthetic that has made Scorsese such a popular and accessible filmmaker. Truffaut's influence can be seen in less showy moments, too, namely the jarring cuts in "Mean Streets" when Harvey Keitel's head hits the pillow and during Travis Bickle's festering "Listen, you screwheads" monologue in "Taxi Driver."

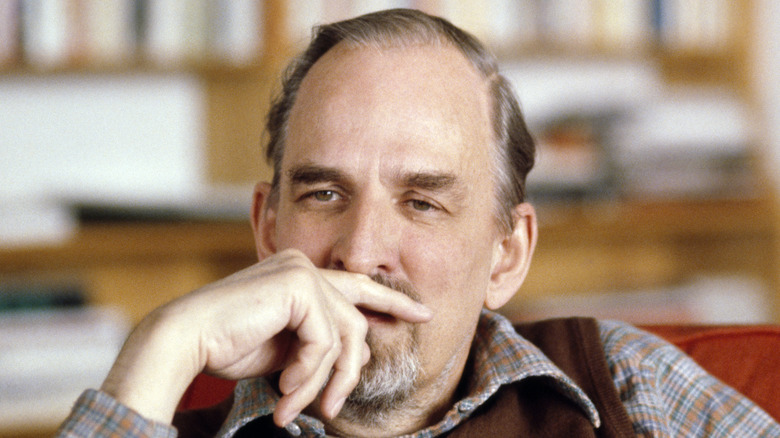

Ingmar Bergman

Scorsese's admiration for Swedish filmmaker Ingmar Bergman can be summarized with this most laudatory quote: "If you were alive in the 50s and the 60s and of a certain age, a teenager on your way to becoming an adult, and you wanted to make movies, I don't see how you couldn't be influenced by Bergman."

Such praise was expanded upon in "Trespassing Bergman," a documentary ode in which Scorsese and numerous other filmmakers convened in Fårö — the remote Swedish island on which Bergman lived — to discuss the director's work. "[He makes you feel] that anything can be done [with] storytelling visually and with dialogue," Scorsese said in his usual rapid-fire cadence. "What was most inspiring all along was the constant spiritual debate... transcendent debate."

Bergman, who died in 2007, lived to see the bulk of Scorsese's work and he expressed his admiration for it on numerous occasions. For example, when Bobbie Wygant asked him about the link between "Taxi Driver" and the attempted assassination of President Ronald Reagan, Bergman said that Scorsese's film was "about violence on the highest artistic level" and added that he was not responsible for the president's shooting.

John Cassavetes

In a Charlie Rose interview, Scorsese recalled John Cassavetes's plainspoken reaction to "Boxcar Bertha," Scorsese's second feature film: "Marty, you've just spent a whole year of your life making a piece of junk ... Don't get hooked into the exploitation market, just try and do something different." Scorsese harbored no hard feelings. Instead, he declined Roger Corman's offer of more B-movie fare and wrote "Mean Streets," a film that Cassavetes affected with more than just off-color motivation.

Scorsese's respect for Cassavetes began with "Shadows," his 1959 improvised drama that was a great source of inspiration for the aspiring filmmaker. "[It] gave me the urgency and the courage to actually try to make films," Scorsese told the New York Times, "To an extent, in terms of style, I guess I've been going for a cross between 'Shadows' and 'Citizen Kane' all along."

Aside from giving Scorsese a "shot in the arm" when he needed it most, Cassavetes also taught him the value of improvisation. Scorsese has carried this technique through his work and the best example of it has to be his mother Catherine's wonderfully natural turn in "Goodfellas," which she delivered with no script and little preparation beyond her son's advice to "just welcome [the character's] son home... she hasn't seen him in a while" (via Entertainment Weekly).