When Should Alfred Hitchcock Have Won His Oscar? An Investigation

(Welcome to Did They Get It Right?, a series where we look at Oscars categories from yesteryear and examine whether the Academy's winners stand the test of time.)

When we think of great Hollywood directors, we think of names like John Ford, Frank Capra, Billy Wilder, and moving on up to the likes of Steven Spielberg. These are filmmakers who not only had strong artistic and creative instincts and abilities, but they also knew how to translate those skills into making films that appealed to gigantic mass audiences. They made the films that Hollywood always strives to make.

Unquestionably, another filmmaker who belongs on that list is Alfred Hitchcock, the so-dubbed "Master of Suspense." That moniker suits him perfectly, as he was able to craft some of the most tense pictures ever produced in Hollywood. He perfectly understood set-up and payoff. He knew how to ride the line between euphemism and explicitness, crafting lascivious, exciting tales that tapped into our base selves. You look at the list of his decades-long filmography and see countless four-to-five-star movies, including some of the greatest ever made.

Something that differentiates Hitchcock from the likes of Ford, Capra, Wilder, and Spielberg is that the Academy never recognized him for his directorial achievements. Meanwhile, those four other directors earned a minimum of two wins. Hitchcock garnered a total of five nominations for Best Director and fell short every single time, putting him in a tie for the most nominations in the category without a win.

Why did someone who everyone agreed was a master of his craft never get over that hump? Let's examine each of his five nominations to see if the Academy bungled their selections or perhaps the stars just never aligned adequately for Hitchcock.

Rebecca

Throughout the silent film era and the 1930s, Alfred Hitchcock had been making films in England for British companies. His first Hollywood production was an adaptation of the classic Daphne du Maurier novel "Rebecca." At the Oscars, it was a smash success and earned 11 nominations, far and away the most of the year. Making things even better, it won Best Picture — quite a way to make a Tinseltown splash.

Beyond that Best Picture win, though, "Rebecca" had a fairly rough night at the Oscars, winning just one other award for George Barnes' gorgeous black-and-white cinematography. This was one of those years at the Oscars where they really spread the wealth around, with no film winning more than three awards. "The Thief of Baghdad" took home three, and "The Philadelphia Story" and "Pinocchio" won two each. Also winning two was "The Grapes of Wrath," which included a Best Director win for John Ford.

Ford was an Oscars juggernaut. He holds the record for the most wins of all time with four, and astoundingly, he did that by only getting nominated five times, ironically losing for a film many would consider his best in "Stagecoach." "The Grapes of Wrath" marked Ford's second win, and he came back the very next year and won for "How Green Was My Valley." The numbers show that if you were up against John Ford, you were screwed, especially for someone newer to Hollywood like Hitchcock.

Like the acting categories, some sense of paying dues goes on in the voters' minds. They don't want to give someone an Oscar too early in their career at the expense of Hollywood stalwarts or for fear that their career won't warrant that distinction going forward. Hitchcock would need some more time.

Lifeboat

Four years later, Alfred Hitchcock received his second Best Director nomination for a film not often discussed nowadays from the director's filmography, "Lifeboat." Where "Rebecca" was the nominations leader, "Lifeboat" only managed to garner three, which did not include one for Best Picture. Hitchcock was not the only director who didn't crossover into both categories, as Otto Preminger earned his first nomination for the film noir classic "Laura."

Hitchcock and Preminger ultimately lost the award to Leo McCarey for the Bing Crosby-starring musical comedy "Going My Way." The "Rebecca" year was one to spread the wealth, but that was not the case here. "Going My Way," the highest-grossing film of 1944, took home an impressive seven wins that evening, including Best Picture, Best Actor, Best Supporting Actor, Best Screenplay, and, yes, Best Director. To overcome a steamroller like that, the overall recognition of "Lifeboat" needed to be a lot stronger than it was, and Hitchcock never really had the juice.

Seeing how history looks back on all the films nominated for Best Director, the one we should be surprised didn't win isn't Alfred Hitchcock but Billy Wilder, for directing one of his signature masterpieces in "Double Indemnity." The landmark noir — which has been the inspiration to so many filmmakers and still plays like gangbusters nearly 80 years later — received seven nominations and went home empty-handed.

Wilder took home the award the following year for "The Lost Weekend," which also won Best Picture, Actor, and Screenplay. While the history books ultimately show having two Best Director Oscars (the second of which we'll get to later) and "The Lost Weekend" is a perfectly good movie, I think those history books would look a little better had that first win come for "Double Indemnity" instead.

Spellbound

Had Billy Wilder won the previous year and the Academy didn't feel like awarding him for the second year in a row for "The Long Weekend," perhaps that could have been the time to award Alfred Hitchcock. He, too, received back-to-back Best Director nominations, this time for the far better remembered "Spellbound," starring Ingrid Bergman and Gregory Peck. "Spellbound" earned a healthy six nominations — just one less than "The Lost Weekend" — and made its way into Best Picture.

Unfortunately for Hitchcock, a couple of things stood in the way. As much as I like my hypothetical Oscars history, that isn't what actually happened. "The Lost Weekend" was the overwhelming frontrunner this year, having won Best Picture at both the Golden Globes and New York Film Critics Circle Awards. The chances of it not winning big at the Oscars, especially for Ray Milland in Best Actor, were slim to none.

Having acting nominations for your film is always a boon to your movie. While Ingrid Bergman and Gregory Peck were both nominated that year, they were both for performances in different movies, with Bergman in "The Bells of St. Mary" and Peck in "The Keys of the Kingdom." Strangely enough, they were both playing religious figures, a nun and a priest, respectively. The only acting nomination for "Spellbound" was for Michael Chekhov in Best Supporting Actor, which isn't the result you want when your film is headlined by two massive movie stars.

This year was always Billy Wilder's to lose, and he didn't. It wouldn't shock me if Hitchcock came in second place, though Leo McCarey once again had the most nominated film of the night with "The Bells of St. Mary," which is also a sequel to "Going My Way." And the Academy doesn't like franchises.

Rear Window

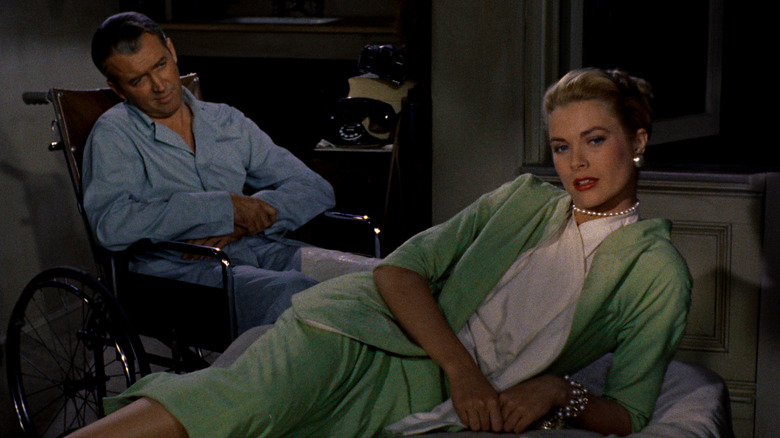

It took almost a decade for Alfred Hitchcock to earn his penultimate Oscar nomination, and this is truly one of the big guns, as he rightly got the recognition for arguably his best film in "Rear Window." Although we all know this to be one of the great works of Hollywood cinema, its fate was quite similar to "Lifeboat." Amazingly, this was another instance where Hitchcock earned a Best Director nomination, but "Rear Window" itself didn't make it into the Best Picture category. It only earned four nominations total, and it lost all of them.

Like his previous two years, Hitchcock was up against another juggernaut, one that took home an impressive eight awards. Though that status is a little bit questionable with hindsight for pictures like "Going My Way" and "The Lost Weekend," that wasn't the case here. This was the year of Elia Kazan's "On the Waterfront." Though the movie was tinged with controversy, as it was essentially a film about Kazan justifying why he named names during the Joseph McCarthy-led witch hunt hearings to find Communists in Hollywood, it was still a sterling piece of drama that featured a performance from Marlon Brando that helped change the way film acting was done.

This is one of those years where the directors' branch did its own thing, crossing over with Best Picture in only two instances: Kazan, and George Seaton for "The Country Girl." The lone director nominees alongside Hitchcock were William A. Wellman for "The High and Mighty" and our old pal Billy Wilder for "Sabrina." As a directorial achievement, I believe Hitchcock to be the clear-cut winner for "Rear Window," even with "On the Waterfront" there. But realistically, the full-throated support for Hitchcock's masterpiece wasn't there. Sometimes at the Oscars, you're a victim of circumstance.

Psycho

Alfred Hitchcock's final Best Director nomination came six years later, and it was again for another film many would call the director's finest work. His final nod came for the genre-changing horror film "Psycho." Now, I'm going to sound like a broken record here, but he once again did not get into the Best Picture category, with the film capping out with four nominations just like "Rear Window."

Winning Best Director is hard enough. Winning it when your film isn't nominated for Best Picture is even harder. Here's how rare it is: it hasn't happened since the second Academy Awards back in 1930. The disconnect comes from the fact that the directors' branch votes on who gets nominated, but the Academy, as a whole, votes on the winner. A Best Picture nomination shows broad support, and Hitchcock rarely had that, even though the directors consistently knew what an expert craftsman he was.

I wouldn't have given it to him for "Psycho," and that isn't to denigrate his work in the slightest. He's in the unfortunate spot that "Psycho" just so happened to be competing against my favorite film of all time, which actually did take home Best Picture and Director that year. The winner was "The Apartment," meaning that Hitchcock was foiled by Billy Wilder once again.

It's rather amazing that the two competed against each other four times over the course of 16 years. Along with the lack of Best Picture support, sometimes you just get put in a rough spot with who you're nominated against. In this instance, he was against what I consider to be the best film ever made, and beating that is a tall order to fill. If it hadn't come up short there, it'd be my new favorite film of all time.

When Hitchcock wasn't nominated

For someone who made dozens upon dozens of films, more surprising to me than Alfred Hitchcock not winning an Oscar is his only being nominated five times. For a lot of people, the biggest head-scratcher would be him not being nominated for his 1958 psychological thriller "Vertigo." This is a film that recently was voted as the second-greatest film of all time in the Sight and Sound poll (where it was formerly number one). And I also consider it to be Hitchcock's best, most complicated work.

But "Vertigo" earned just two Oscar nominations for Best Sound and Best Art Direction. As is often the case with classics, the reception to the film at the time of its release wasn't all that glowing, with people admiring some aesthetic elements but not connecting with the story at all. It wasn't ever going to make the big categories.

The two I'm most surprised by the lack of nominations for Hitchcock were 1946's "Notorious" and 1959's "North by Northwest." In the case of the former, he was up against stiff competition with David Lean for "Brief Encounter," Frank Capra for "It's a Wonderful Life," Robert Siodmark for "The Killers," Clarence Brown for "The Yearling," and the winner, William Wyler for "The Best Years of Our Lives." Again, I wouldn't have given Hitchcock the award this year, but you could easily swap him in for Clarence Brown.

The "North by Northwest" year — where William Wyler won again for "Ben-Hur" — is one where the Best Director lined up with Best Picture for four of the five slots. That lone director nom went to, of course, Billy Wilder for "Some Like It Hot," which I'd say was the better choice. So, getting in that year would be quite tough. There's always a roadblock.

Getting a Best Picture nomination, but not Best Director

As I have already written about, Alfred Hitchcock had a very hard time winning Best Director because his films rarely received widespread support from all the different branches of the Academy. However, Hitchcock did receive four Best Picture nominations over the course of his career.

I've mentioned two of them already with "Rebecca," which won, and "Spellbound," which lost to "The Lost Weekend." That should mean two of the other three movies he got nominated for were nominated for Best Picture, right? As it happened, no. In fact, he had two instances in his career of getting recognized for that top prize but missing out on a Best Director nomination.

The first of these was "Foreign Correspondent." There is a very good reason for this: he was already nominated for "Rebecca" that same year. This was a time when the Oscars had 10 Best Picture nominees instead of five, and both films got in there. You would think that would give him an edge, but two other directors also had two Best Picture nominees that year: Sam Wood for "Kitty Foyle" and "Our Town," and Best Director winner John Ford for "The Grapes of Wrath" and "The Long Voyage Home." Something that should've been an advantage turned out to be ordinary.

The very next year, "Suspicion" got nominated for Best Picture, but this was another year with 10 nominees. Despite the fact that Joan Fontaine won Best Actress for the film, beating her sister Olivia de Havilland, this was always going to be an also-ran. Plus, he would've lost to John Ford again — and if someone else should've won that year, it was Orson Welles for a little film called "Citizen Kane."

When Hitchcock should have won

Previously, I've looked through the Oscar nominations for Glenn Close and Peter O'Toole to see when they should have won their elusive Academy Awards. In both cases, the answers were quite clear. The Academy either bungled the selection of the winner, or history had shed greater light on the category and pushed them to the front of the pack. I could point to the exact right answer if someone said, "Glenn Close should have an Oscar."

In the case of Alfred Hitchcock, the answer isn't easy. For someone so many people, including myself, consider to be one of the best people ever behind the camera, he constantly fell victim to incredible competition or contemporaneous circumstances that prevented him from walking up to the podium to collect that golden statue.

If my vote was the only one that mattered, I believe "Rear Window" should be the film Alfred Hitchcock won his Best Director Oscar for — but I cannot begrudge anyone for voting for Elia Kazan for "On the Waterfront," which I also consider to be an exceptional film even if the politics behind it really bother me. To say the Oscars blew it would just be wrong.

I would also like him to have won for "Vertigo," beating out Vincente Minnelli for the deeply dull "Gig." But even if "Vertigo" was received very well at the time and he got nominated, I still think Hitchcock would've struggled mightily to win that award because "Gigi" was another juggernaut, winning all nine of the categories in which it was nominated. Ultimately, Alfred Hitchcock drew the short straw when it came to the Academy Awards, and although he deserved to win Best Director, quality is only a small part of what gets you in the winners' circle.