Snow White And The Seven Dwarfs Was Walt Disney's Biggest Box Office Gamble

(Welcome to 100 Years of Disney Magic, a series examining the history, achievements, and legacy of The Walt Disney Company over the last century. Part 5, "Silly Symphonies: The Oscar-Winning Disney Animation Series That The Studio Forgot" looked at the groundbreaking, critically acclaimed shorts the studio produced in the '30s. In Part 6, we finally talk about "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs," the first full-color animated feature film and arguably Disney's most important contribution to cinema.)

What can I say about "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs" that hasn't already been said?

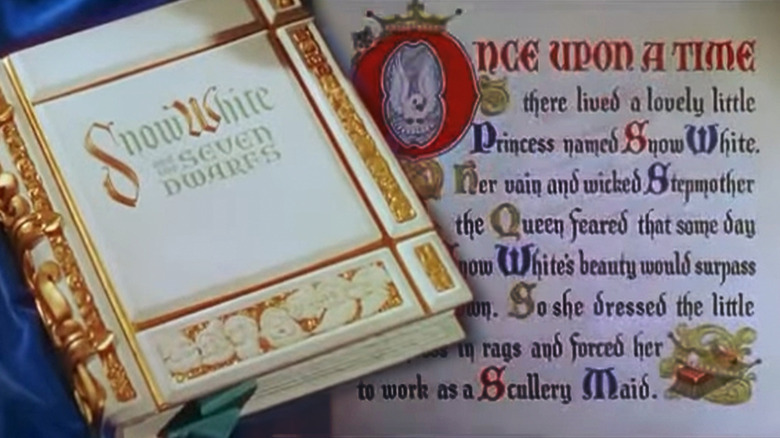

The 1937 film changed the world. Mere years after Walt Disney Productions shook up the animation industry by putting sound in "Steamboat Willie" in 1928 and then color in "Flowers and Trees" in 1932, the team set their sights on revolutionizing the world of cartoons once again: with a feature-length, full-color, animated fairy tale.

"Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs" was a sensation. It dominated the box office, temporarily holding the record for the highest-grossing sound film until "Gone with the Wind" outperformed it in 1939. This was the cultural dominance Walt Disney yearned for.

Following the massive success of "Snow White," the studio would pivot away from the Silly Symphony shorts to focus on producing more high-quality feature-length animation; the result was titles like "Pinocchio," "Fantasia," and "Dumbo" that were critically acclaimed but financially disappointing. For years, "Snow White" was the high-point in the company's history.

Sergei Eisenstein, the Russian director and motion picture theorist who pioneered the montage, famously said that "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs" was the best movie ever made. Time listed the film as 13th in its list of "The 25 All-TIME Best Animated Films." In 2019, Rolling Stone listed "Snow White" as the fourth.

"Snow White" is a masterpiece.

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs is unlike anything else

Animation scholar J. B. Kaufman, in an essay for the Library of Congress, writes of "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs":

Some films achieve greatness because of their historical significance, others because of their artistry. A relative few can claim both. Walt Disney's "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs" is one of the films in this charmed inner circle, a motion picture whose historical importance is inextricably linked with the magnitude of its artistic accomplishment.

My friend Eric, a long-time animator, once told me the tragedy of his industry is knowing that we'll never again see the level of artistic ambition and innovation displayed in "Snow White." Yes, it was the first of many color animated feature films, but its cultural significance is so much more. Disney reinvented the wheel with this picture, challenging every convention. The animators used larger cels to fit in more fine detail. They created the multiplane camera, which gave scenes additional depth. Walt's story department turned the characters from the thin archetypes of the fairy tale to unique, memorable and charming people.

Rogert Ebert argues in his 2001 review for "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs":

Nothing like the techniques in "Snow White" had been seen before. Animation itself was considered a child's entertainment, six minutes of gags involving mice and ducks, before the newsreel and the main feature. "Snow White" demonstrated how animation could release a movie from its trap of space and time; how gravity, dimension, physical limitations and the rules of movement itself could be transcended by the imaginations of the animators.

Walt Disney foresaw the short life of shorts

It was inevitable that someone in Hollywood was going to experiment with a feature-length, full-color animation. Heck, technically Quirino Cristiani, an Italian-Argentine animator, made the first feature-length animation, "El Apóstol," as well as the first feature-length animation with sound, "Peludópolis." (As is the case for many black-and-white films, these are unfortunately lost to time.) The point is, Disney was very good at predicting where the market was headed; as much as he was trailblazing, he was also reactionary. This isn't a criticism — in fact, quite the contrary. Although he had a rocky start in the industry, Walt would become a titan precisely because he knew how to look to the future and respond to changing trends.

Following the success of the Mickey Mouse shorts and the Silly Symphonies, Walt Disney recognized that he was in a position to dominate the market, but the studio would need to do more than maintain the status quo to stay competitive. As Neal Gabler describes in the biography "Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination," the shorts were profitable (and during the Depression, no less!) but their potential was severely limited. The company would never see major return on the shorts because they were seen as "filler" — the main ticket-seller was the feature film presentation. Given the status of the cartoons as essentially bonus material, there was no guarantee that his shorts — as masterful as they were — would continue to sell to theater operators.

If Walt Disney Productions was going to be in "the big leagues" with the other studios, he would need to start competing with them directly — and it wouldn't be enough for Walt to just make a feature film. It had to be a feature-length cartoon.

Cartoons were Disney's only option

By the mid-'30s, Walt Disney Productions had risen to the very top of its field, releasing award-winning animated content. Even though it had never been done before — and would be prohibitively expensive to produce — Walt's only option for breaking into feature films was a high quality animation, featuring all the techniques the Silly Symphonies had become known for.

Despite how risky it was, an animated feature was actually the safest bet for Disney. Back when the company was called Disney Brothers Studio, Walt experimented with live-action, but the Alice Comedies were not the stirring success he had hoped for. The plain truth was that Walt was out of his depth when it came to cinematography. Before moving to Hollywood, the Kansas City native had no previous technical experience or training with photography (or lighting ... or acting). As a lifelong artist, he understood the basics of drawing and could apply that knowledge and skill to the emerging art form of animation, seamlessly transitioning into more of a mentorship role overtime. By 1935, he had grown an entire studio of professionals trained specifically in illustration, animation, and painting. They all studied film, and used the movements, framing, and mise-en-scene of live-action cinema as inspiration, and he had cinematographers, but they were specialized in animation, first and foremost. Sure, Disney could have made his first feature film in live-action, but he'd be starting over again.

There was also an interest in the market for further experimentation in the medium by the early '30s. With shorts like "The Three Little Pigs" and "The Band Concert," cartoons were beginning to be seen as more than silly kid fare. And there's ample evidence that this instinct to produce a feature-length animation predates "Snow White." Gabler references unrealized plans for an "Alice in Wonderland" project as early as 1932, as well as an adaptation of the popular book "Bambi: A Life in the Woods." Of course, the issue, as it always did for Walt, came down to money.

Making animation is expensive

Those who are interested in Hollywood history likely know a few key things about "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs": that it was the first full-color feature-length animation, that it was a huge box office success, and that its production was egregiously expensive. The budget ballooned from the original $250,000 to an estimated $1.5 million — more than the 1930 war film "All Quiet on the Western Front" and about equal to the Cecil B. DeMille's Biblical Epic "The Ten Commandments." Today, the idea of Disney spending a fortune on an animated feature film is more predictable than anything, but in the mid-'30s, it was downright wild. Cartoons were, after all, seen as novelties more than anything else.

By 1934, Disney was the undisputed king of cartoons, and the Silly Symphonies series fetched rental rates about 50% higher than Disney's competitors — yet, that year saw a profit of just $600,000 (per Gabler). So spending even just $250,000 on a totally untested project was the equivalent of about 40% of a year's total profits on one huge gamble. To put this in perspective: Today, Disney regularly brings in billions of dollars each year from theaters alone, so spending $150 million on a movie like "Frozen 2" is not going to sink the company. 2012's mega-bomb "John Carter" — infamously one of the most expensive movies ever — lost the company something like $200 million dollars, but that was only a fraction of its annual box office income. Spending $1.5 million on film production during the Great Depression with the kind of money Disney was bringing in ... a bold move, to say the least.

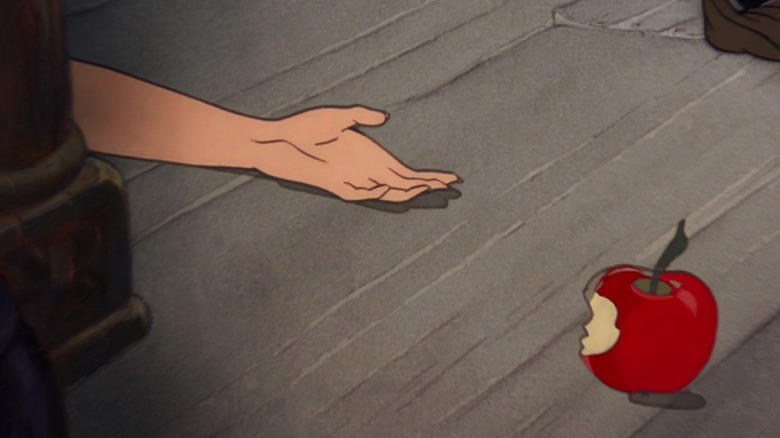

Walt Disney Productions burnt through the initial "Snow White" budget quickly, and in the years it took to complete the film, the studio's finances became increasingly precarious.The project spent years in pre-production — recruiting and training new animators (later he would literally establish an art school, CalArts), studying movement, developing the story, etc. — and animation didn't start until approximately 1936, starting with roughs and then eventually finalizing model sheets in the fall. Walt would eventually dig into his own pocket, selling his beloved car, mortgaging his house, and even taking out money on his life insurance to keep the project going. If "Snow White" hadn't been a success, the studio's Mickey Mouse cartoons likely wouldn't have been enough to save the studio.

Why Disney started with Snow White

Walt Disney knew how to tell a story. Famously, the "Snow White" project began in earnest after Walt himself acted out the story for his animators — taking hours to do so, and performing all the roles (by all accounts, it was quite something to behold). His passion was infectious, and would carry the project through many delays and stumbling blocks.

So why was the first feature film "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs" and not "Alice in Wonderland" or "Bambi"? Part of it was funding — for various reasons, the capital needed for the previously suggested projects never materialized — but it was also personal. According to Gabler, Walt had seen a production of the fairy tale as a child back in Kansas City and it left an indelible impression on him.

Walt said he could remember seeing a 'Snow White' play as a boy, though he was probably recalling a film version of the play starring Marguerite Clark that screened on January 27 and 28, 1917 ... to accommodate the crowds, the film was projected simultaneously on four screens arranged at right angles ... Walt, seated high in the gallery, said that he could see on one screen what was going to happen on the adjacent one, which made the show seem somehow even more magical.

Gabler also notes that Walt stated he chose "Snow White" for its "aesthetic potential" — the story lent itself to drama, gags, adventure, and even romance. Bob Thomas makes a similar argument in his biography "Walt Disney: An American Original," although he argues the childhood memory was not the driving reason for Walt picking "Snow White" for his first feature film.

But his choice of "Snow White" was more pragmatic than sentimental. He recognized it as a splendid tale for animation, containing all the necessary ingredients: an appealing heroine and hero; a villainess of classic proportions; the Dwarfs for sympathy and comic relief; a folklore plot that touched the hearts of human beings everywhere.

Gabler takes this one step further, suggesting there may also have been "deep-seated psychological reasons" for Walt choosing "Snow White." The story featured elements that reflect the animator's own experiences and ambitions.

"Snow White" had nearly all the narrative features — the tyrannical parent, the sentence of drudgery, the promise of a childhood utopia — and incorporated nearly all the major themes of his young life, primarily the need to conquer the previous generation to stake one's claim on maturity, the rewards of hard work, the dangers of trust, and perhaps above all, the escape into fantasy as a remedy for inhospitable reality. ... "Snow White" was the story of Walt Disney's personal growth, the story of what he had had to surmount and what he had achieved.

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs changed the world

Other film critics and scholars have attributed different factors at play in Walt's attraction to the story of "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs." Richard Schickel famously alluded to an "anal-fixation" in the dwarfs' "rump-butting" in "Snow White" (per Roger Ebert). Douglas Brode in "From Walt to Woodstock: How Disney Created the Counterculture" sees in "Snow White" both a rejection of conformity and a romantic — almost religious — view of nature. Tracey Louise Mollet, in "Cartoons in Hard Times: The Animated Shorts of Disney and Warner Brothers in Depression and War 1932 – 1945," conversely presents Disney's animation during this time as an expanding tool for ideological messaging. Regardless of what, exactly, drew Walt to the Brothers Grimm story, the passion and ambition he brought to the project was unparalleled.

Following the film's debut in 1937, the critics raved. The Hollywood Reporter wrote "The drawing and animation go far beyond anything seen before" and "The production marks a milepost of motion picture progress, for it is in conceivable [sic] that this will not have many successors." John C. Flinn Sr. wrote in Variety, "So perfect is the illusion, so tender the romance and fantasy, so emotional are certain portions when the acting of the characters strikes a depth comparable to the sincerity of human players, that the film approaches real greatness. It is an inspired and inspiring work." Frank S. Nugent wrote in The New York Times in January 1938, "Sheer fantasy, delightful, gay and altogether captivating, touched the screen yesterday when Walt Disney's long-awaited feature-length cartoon of the Grimm fairy tale, 'Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs,' had its local premiere at the Radio City Music Hall."

A glorious (if temporary) victory

Walt Disney Productions could not have hoped for a better reception — "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs" even won a one-of-a-kind Academy Award. The custom statuette consists of a normal Oscar and seven miniature ones, and was presented to Walt Disney by Shirley Temple. After several gruelling years, Disney enjoyed a significant high following "Snow White" — one that Walt himself would not enjoy again for many years.

"Snow White" was a special project for Walt. The parallels between the story and his own childhood experiences and personality are obvious — not to mention this was the film that catapulted the studio into real stardom. "Snow White" would serve as the basis of one of the opening day attractions for Disneyland in 1955. In a CBC interview, Walt Disney spoke of his experience with "Snow White," and his eyes twinkle with delight at the recollection. He jokes, "the banker, in fact, was losing more sleep than I was."

He's shockingly humble. Of course, one can't help but wonder how much of this is that famous "Uncle Walt" persona — Disney was often described as an excellent actor and storyteller, after all. And yet, I can't help but be drawn in. "Snow White" was such a monumental achievement — of course Walt would remember that time fondly.

After all, it was followed by a much darker period.

Join us next time for 100 Years of Disney Magic Part 7, where we'll dive into the complicated legacy of Disney during World War II.